MRRL Hall of Fame

RUSS GIBB

- Details

- Category: Inductees

- Created: Thursday, 22 July 2021 16:19

- Written by Gary Johnson

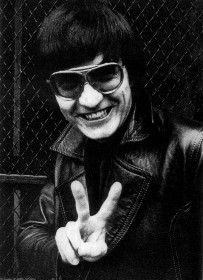

Russ Gibb was one of the most important nonperformers in the Motor City’s colorful music scene. He was described by Brian McCollum of the Detroit Free Press as “the farsighted arts lover and entrepreneur who helped ignite Detroit's live rock scene. Gibb was a larger-than-life character known to local music fans as "Uncle Russ," and he transformed the Grande Ballroom into Detroit's psychedelic-rock palace in 1966, a game-changing move that launched an indelible chapter in Detroit music history.”  "Uncle Russ" Gibb

"Uncle Russ" Gibb

David A. Carson’s excellent book on Detroit rock and roll, (Grit, Noise, and Revolution), provides us with an in-depth look at the life and times of Russ Gibb. Carson wrote that Gibb was born in the Detroit suburb of Dearborn in 1932. He graduated from Michigan State University in 1953 with a degree in educational radio and television administration. While teaching in Howell, Michigan, he also worked weekends handling production duties and some weekend deejay work for several Detroit-area radio stations.

It was during a trip to San Francisco to visit his friend Jim Dunbar, a popular radio personality at station KGO, that he had the opportunity to check out Bill Graham’s newly opened music venue at the Fillmore Auditorium. The performance by The Byrds, amid a light show with strobe lights, was an experience that dramatically changed Gibb’s life.

Thinking that a similar venue would be great for Detroit, Gibb set out to find a suitable facility after he returned to Michigan. He found it in an old, abandoned big-band ballroom, located at 8592 Grand River Avenue, one block south of Joy Road.

The Grande Ballroom was built in the gothic style in 1930, but it was long past its prime when Gibb signed a rent-to-buy deal with the building’s owner. Although it had most recently been used as a roller rink and a mattress warehouse, Gibb immediately made plans to open it as a rock emporium even though it was located in a tough neighborhood.

While searching for local talent to play at the Grande, he was introduced to John Sinclair, the music columnist for the Fifth Estate, a counterculture periodical based in Detroit. Sinclair was a friend and fan of a local hard rock band known as the MC5, and he recommended them to Gibb.

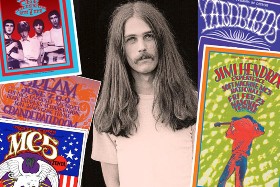

Looking for someone who could produced colorful poster-style promotions that would emulate what he had witnessed in San Francisco, Gibb was introduced to graphic artist Gary Grimshaw by the MC5’s lead singer, Rob Tyner. Grimshaw had been stationed in San Francisco while serving in the navy, and had been impressed with the style of the Fillmore posters. He was soon designing posters and picture sleeves for the MC5, and then producing light shows at the Grande as part a crew called Trans-Love Energies’ Magic Veil Light Company along with Leni Sinclair and Jerry Younkins.  Gary Grimshaw

Gary Grimshaw

Grimshaw held Gibb in high regard. In an interview, Grimshaw described him as a hard-core capitalist who was into rock and roll and danger. “He was always smiling and confident,” Grimshaw said. “Gibb was fearless. He was ‘Uncle Russ!’ He was the Grande Ballroom. Sure, he had a team behind him, a very fine team, but he took all the media heat and dealt with it with style and grace.”

By 1967, posters appearing along the streets of Detroit promoting the Grande shows as well as positive word-of-mouth helped make the Grande the place to be every weekend. Grimshaw was soon joined by Carl Lundgren and Danny Dope to produce the posters, handbills, and flyers that promoted upcoming shows at the Grande “Russ never interfered with the art,” Grimshaw recalled. “He seemed happy to get any art, especially at the bargain basement prices he was willing to pay, and we were willing to accept.”

Carl Lundgren was born in Detroit in 1947. During his senior year in high school, he started playing professionally as a folksinger in local clubs and coffee houses. He then decided to pursue a career in art and subsequently attended some art schools in California. While there, he was exposed to the emerging rock poster scene, and he began working with Grimshaw in 1967 after he returned to Detroit.  Grande poster by Carl Lundgren

Grande poster by Carl Lundgren

Over the next few years, Lundgren produced some of the era's most memorable lithographs, advertising Grande appearances by the Chambers Brothers, Buddy Guy, Fleetwood Mac, Spirit, the Steve Miller Blues Band, Country Joe and the Fish, Howlin’ Wolf, Procol Harum, Pink Floyd, Ten Years After, the Jeff Beck Group, John Lee Hooker, and the Jefferson Airplane.

Gibb opened the Grande on the evening of October 7, 1966. Only about five dozen people showed up for performances by the Chosen Few and the MC5, but attendance increased quickly. During the first year or so, the Grande presented mostly Detroit-based bands like the MC5, the Scot Richard Case (SRC), the Rationals, Bob Seger and the Last Heard, the Jagged Edge, the Woolies, and the Thyme.

Starting near the end of 1967, however, Gibb was able to start booking national acts like Vanilla Fudge, Cream, the Yardbirds, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, Canned Heat, the Byrds, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Blood, Sweat, and Tears, Led Zeppelin, and the Who. The Who loved playing at the Grande, and they would later perform their rock opera Tommy there for the first time in the United States. Gibb and Pete Townshend playing "Tommy" at WKNR

Gibb and Pete Townshend playing "Tommy" at WKNR

Gibb credited John Sinclair with playing a large role in the success of the Grande. “He had a better feel for the market than I when we started,” Gibb said. “I was familiar with the social structure of young people as ‘frats’ and ‘greasers.’ The kids coming to the Grande were different, and John understood them and the music they liked, so he wound up recommending a lot of the bands that were booked.” These bookings included up and coming Michigan groups like the Amboy Dukes, the Stooges, Savage Grace, the Frost, and the Wilson Mower Pursuit.

It was during this period that the MC5 started to enjoy popularity on a much larger scale. After being signed to Elektra Records in 1968, the band recorded their legendary “Kick Out The Jams” album live at the Grande during a two-night stand on Devil’s Night on October 30th and Halloween night on October 31st. The album was released in February 1969, complete with Rob Tyner’s infamous ‘Kick out the jams, motherfuckers!’ shout before the opening riffs. The song offended label executives at Elektra as well as parents and other adults, and the MC5 quickly became lightning rods for both controversy and censorship.  The MC5 on the Grande stage

The MC5 on the Grande stage

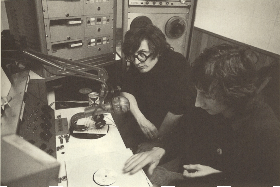

The Grande Ballroom was only one part of Russ Gibb’s colorful career. He was also employed as a deejay at WKNR-FM. Besides playing records, Uncle Russ would “rap” with listeners on the air. Having the proprietor of the Grande on the air each weekend was a feather in the cap of WKNR. Gibb’s show was very popular, and it worked very well for both him and the Grande.

Gibb’s most famous broadcasts involved the Paul McCartney Death Rumor. It started on Sunday, October 12, 1969, when a caller mentioned the rumor and then suggested that Gibb play the Beatles’ “Revolution No. 9” backwards on the air after Uncle Russ expressed his doubts. When “number nine” was played backwards, it sounded eerily like “turn me on dead man.”

Gibb went on to play some of the other clues that the listener suggested, and the story grew from there. Gibb, John Small, and Dan Carlisle put together a special two-hour program called The Beatle Plot that was devoted to the rumor, and Life magazine showed up in the studio the night of the first broadcast. The magazine ended up tracking down a very alive Paul McCartney on his farm in Scotland for a cover story on the rumor/hoax. The affair resulted in a windfall of publicity for Uncle Russ and WKNR and an increase in the sales of Beatles albums across the country.  Gibb and the Paul Is Dead hoax

Gibb and the Paul Is Dead hoax

1969 also saw the Grande come under fire from Creem magazine over the “rapidly deteriorating” condition of the ballroom and complaints from both the bands who played there and the fans who came to see them about the horrible condition of the venue’s bathrooms. This, despite the fact that Gibb had been an early investor in Creem.

In the meantime, Gibb now had a rival to threaten his livelihood with the opening of the Eastown Theatre. The venue, which held around seventeen hundred people, was run by Aaron Russo, a promoter from Chicago. In response, Gibb closed the original Grande, and struck a deal to move his operation to the Rivera Theater, located just around the corner. Now called the Grande-Riviera, the venue had a capacity of around twenty-seven hundred, but the elephant in the room was whether Detroit could support two ballrooms.

After a lot of verbal sparring in the press between Gibb and Russo, the two reached an agreement with promoter Bob Bageris to end the competition. As a result, Gibb ceased operations at the Grande-Rivera and reopened the original Grande Ballroom. He then staged his final show at the legendary venue on January 23, 1970. Not long after, Aaron Russo returned to Chicago and Bob Bageris went on to become the leading promoter of major rock concerts in Detroit.

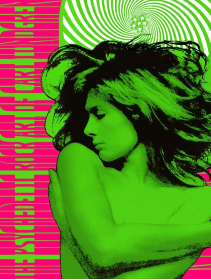

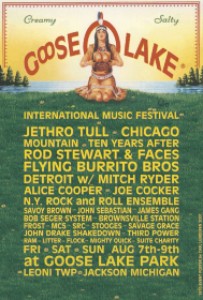

Gibb’s biggest rock and roll event was the Goose Lake International Music Festival held later that summer on August 7- 9 in a 390-acre park in Leoni Township near Jackson, Michigan. The lead promoter was Richard Songer, but he brought in Russ Gibb and his associate, Tom Wright, to help organize the festival with the goal of providing a better planned event with better facilities for rock fans than had been the case at Woodstock.  Goose Lake poster

Goose Lake poster

Goose Lake had a budget of $1 million and was billed as the "world's first permanent festival site". It was projected that 60,000 fans would attend the first festival, but everyone was shocked when a crowd of 200,000 rock music fans showed up.

Those who attended were provided free campsites, free parking, and free firewood. There were restrooms and showers every 500 feet, medical staff, motorcycle and dune buggy trails, and a lake with a beach. The admission price for the three-day event was $15.00, and entry tokens in the style of poker chips were sold to avoid the counterfeiting of paper tickets. To keep gate crashers out, the site was surrounded by a high chain-link fence topped by barbed wire.

The Goose Lake stage was built on a large, revolving turntable with two performance spaces so that the previous band could disassemble its gear, and the next band set up while the current band was performing. National and international acts performing at the festival included the Faces featuring Rod Stewart, Jethro Tull, Chicago, Ten Years After, the Flying Burrito Brothers, Mountain, John Sebastian, Savoy Brown, and the James Gang.  Goose Lake poker chip token

Goose Lake poker chip token

Notable Detroit area bands performing included the Bob Seger System, the MC5, the Stooges, the Frost, SRC, Detroit featuring Mitch Ryder, Brownsville Station, Savage Grace, and Third Power. Masters of ceremonies were Teegarden & Van Winkle, who also performed, but the festival became known for widespread, openly visible drug sales and public nudity more than the music.

Unfortunately, the newspaper coverage of the event concentrated on the open drug sales and use at the festival. As a result of the negative publicity, Michigan governor William Milliken denounced the “deplorable and open sale of drugs,” and called for the investigation and prosecution of the “drug pushers” who were present. In addition, Michigan attorney general Frank Kelley said, “I think we have seen the first and last rock concert of that size in Michigan.”

Although Russ Gibb was not charged, Richard Songer was indicted for promoting the sale of drugs. He was acquitted in December 1971, but the district attorney obtained an injunction barring any other public shows at the park. No further rock festivals took place at Goose Lake.

While traveling in England in 1970, Gibb spent time in London with Eric Clapton and Mick Jagger. It was while staying at Jagger’s estate that Gibb first became exposed to cable television via Mick’s home video system. Cable TV had yet to take off in the states, so when he returned home, Gibb bought cable franchises for several Michigan cities; the sale of these in the 1980s would make him quite wealthy. David A. Carson, in his 2005 book Grit, Noise and Revolution, wrote that Gibb and his partner Michael Berry set up a fund called the Dearborn Cable Communication Fund to promote local programming and education.

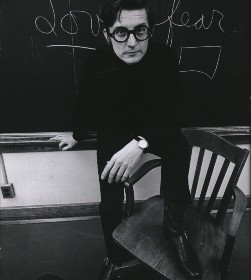

A longtime resident of the Detroit suburb of Dearborn (where Ford Motor Company is headquartered), Gibb spent much of his career at Dearborn High School. It was where he became the school’s video production teacher, setting up a state-of-the-art facility for video and media production. Corey Rusk, in Detroit Rock City, remembered that Gibb “put a bunch of his own money into helping fund Dearborn High School having its own high school TV studio and station that was probably as good as the local television station set-up.”  Russ Gibb in the classroom

Russ Gibb in the classroom

In his teaching practice,” Scott Westerman wrote in an article about Gibb for the WKNR-FM website, “he fought for a brand of education that did not delineate between the arts, letters and numbers. To him there was science in music, there was art in equations and there was genius hidden somewhere inside every kid that sat in his classroom. Russ would probably want to be remembered for nurturing young talent, kids who went on to win Emmys, create computers from paper, develop early smart cards and Internet audio streams, and were catalysts that helped to redefine popular culture.” In addition, Rev. Keith a. Gordon said this of Gibb: “His students adored him. He was the cool uncle they all wanted – a friendly, generous man with great stories.”

Besides his career as an educator, Gibb also did voiceover work for radio and TV commercials, hosted his own TV show, Russ Gibb at Random, and worked in the Gerald Ford White House as the National Director of Youth and Education.

Detroit filmmaker Tony D’Annunzio came to know Gibb while making his award-winning 2012 documentary, Louder Than Love, that chronicled Grande history. “He opened up so much great music to so many people,” said D’Annunzio. “He had his finger on the pulse every step of the way. The part that people connect with most is obviously the Grande Ballroom, but when I met him and started talking to him and got to know him more, that was just a small part of his life. The stuff he did before and after touched so many people. He was monumental.”  MC5's Wayne Kramer, Russ Gibb, and filmmaker Tony D'Annunzio

MC5's Wayne Kramer, Russ Gibb, and filmmaker Tony D'Annunzio

Russ Gibb suffered from poor health in his final years. After a series of medical struggles, he passed away from congestive heart failure at the age of 87 on April 30, 2019.

Dearborn artist Dennis Loren created a poster for Gibb’s memorial that included different aspects of his storied career. “I had first met Russ Gibb in his role as a teacher in Dearborn,” Loren explained. “I had a family connection because my Aunt Nell was his high school English and Drama teacher, and I met him at her house. As he became more successful, Gibb invested in cable television and even Hollywood movies. He also set up a scholarship fund for Detroit area students to go to film school at UCLA. One film he was involved with was the Dead Poets Society. The Robin Williams character was a composite of three teachers – one of which was my aunt. He was a remarkable man, and I always had a special interest in him.”

Russ Gibb was inducted into the Michigan Rock and Roll Legends Hall of Fame in 2021.