Driving down W. King Street, located just a quarter mile north of Owosso’s business district, it seems almost inconceivable that this unpaved road containing a new housing development was once the location of a business that pressed some historic rock and roll records involving both Motown and The Beatles.

The American Record Pressing began in Detroit in 1950 as Vargo Inc. The company was purchased on September 1, 1951, and moved to Owosso, Michigan, a small rural community located 25 miles west of Flint. Its first Owosso location was at 1011 E. Main Street in a building that had been occupied for the previous ten years by the Douglas Trucking Lines. The company was called Vargo Record Pressing when it took over the building, but changed its name to American Record Pressing the following year.

The American Record Pressing began in Detroit in 1950 as Vargo Inc. The company was purchased on September 1, 1951, and moved to Owosso, Michigan, a small rural community located 25 miles west of Flint. Its first Owosso location was at 1011 E. Main Street in a building that had been occupied for the previous ten years by the Douglas Trucking Lines. The company was called Vargo Record Pressing when it took over the building, but changed its name to American Record Pressing the following year.

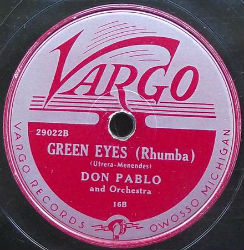

In 1951, the plant had only three record presses and handled only 78 rpm records. Some of those recordings were issued on its own Vargo label. By the end of the decade, however, the demand for 78 rpm records had dwindled, and the orders from record companies were mainly comprised of seven-inch 45 rpm singles and long playing 12-inch albums in both mono and stereo.

American Record Pressing eventually discontinued its Vargo label and became strictly a custom pressing business. It produced records for companies that did not have their own pressing plant. In its earliest days, the business was limited to Detroit customers, but by the end of the 1950's it was shipping to all parts of the country. ARP's customers included a bevy of well-known national labels: Cameo-Parkway and Swan (Philadelphia), Vee Jay, Tollie, and Bamboo (Chicago), Era (Hollywood), Buddah (New York), Sussex (Los Angeles), and Motown, Tamla, Gordy, Soul, Harvey, and V.I.P. (Detroit). In addition, ARP stamped all of the 45 rpm singles that were produced by Fenton Records in the Great Lakes Recording Studio in Sparta, Michigan; and they pressed singles for a host of other small Michigan labels as well.

In 1963, ARP moved its operation two miles west to a 22,000 square foot facility at 1810 W. King St. The building was originally constructed by a company called Owosso Mobile Homes in 1955. The business declared bankruptcy in 1962, and ARP took over the building early in the following year. By this time, American Record Pressing had 14 modern record presses and a complete label printing department.

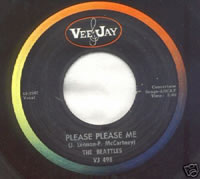

The "Please Please Me" single pressed at ARP with 'The Beattles' misspelled on the label

The "Please Please Me" single pressed at ARP with 'The Beattles' misspelled on the label

ARP pressed the first Beatles record to be released in the United States for Vee-Jay in 1963 at their new location. Vee Jay issued the 45 rpm single of “Please Please Me/Ask Me Why” on February 25, 1963, almost one year before The Beatles first appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show and launched what became known as “Beatlemania”. The single, with the name Beatles misspelled as ‘Beattles’, was not a big seller at the time, but is an extremely valuable collector’s item today.

In 1964, Vee-Jay re-released “Please Please Me” with “From Me To You” as the flipside. Both sides charted on Billboard’s Hot 100, at # 3 and # 41 respectively, in a year that saw The Beatles completely dominate rock and roll. Other Vee Jay artists whose records were pressed in Owosso included The Four Seasons, Jimmy Reed, John Lee Hooker, Jerry Butler, Betty Everett, The Dells, Gene Chandler, and Dee Clark.

Besides pressing records, ARP also produced material for making records. The company had its own machine shop for repairs and for the making of dies and tools related to the record industry. Late in 1960, the company expanded into supplying dies and tools to other record pressing plants, a highly specialized phase of the tool and die business.  The 1972 fire that destroyed the American Record Pressing building

The 1972 fire that destroyed the American Record Pressing building

The company's success was built upon quality of work and service. All record orders received on one day were delivered the next. To accomplish this, orders to all customers, except those in nearby Detroit, Chicago, or Cleveland, were shipped by air. Every night, shipments were driven to the Detroit Metropolitan Airport in Romulus and Willow Run Airport in Ypsilanti so that they could be delivered to customers across the country before noon the next day.

By 1972, the ARP plant had expanded to 60,000 square feet and the company employed 230 people. On October 30, 1972, The facility was completely destroyed by a fire, despite being battled for hours by firemen from Owosso, Corunna, Owosso Township, and Caledonia Township.

Accoring to a statement made to the Owosso Argus-Press by Fire Marshall Clarence Monroe, the fire began in the northwest portion of the factory and was reported to area firemen shortly before 10:30 a.m. The cause was under investigation, and there were no reports of any fatalities.

Owosso Fire Chief Les Reid told the newspaper that the entire northwest section of the building was in flames by the time the fire was discovered by company employees. Reid also stated that firefighters were hampered because the blaze had already had a good start by the time they arrived on the scene, and by the fact that there was only one hydrant in front of the building. His department had to lay its two and a half inch diameter hose all the way from a second hydrant approximately a half mile away.

David Howell, vice president of manufacturing and production at American Record Pressing, told the Argus-Press, "the company definitely will rebuild" and that the monetary loss to the company had yet to be determined. Employees were no doubt relieved to hear him say that temporary offices of ARP would open the following day and that the company payroll would be handled there.

Somewhat more ominous was Howell's statement that a management team from the New York office of Viewlex Inc. were arriving in Owosso later in the afternoon to discuss future operations there. American Record Pressing was a wholly owned subsidiary of Viewlex.

Interesting as the history of ARP was, my primary reason for motoring from Essexville to Owosso, however, had to do with Motown. Over 50 years ago, in a blinding January snowstorm, Berry Gordy Jr. and Smokey Robinson drove from Detroit to the original E. Main St. location of the American Record Pressing company to pick up the boxes containing the first 45 rpm singles ever pressed for Gordy’s Tamla Records. That single, Marv Johnson’s “Come to Me/Whisper”, marked the beginning of what became known as Motown Records.

ARP pressed "Come To Me", the first Tamla single, in 1959

ARP pressed "Come To Me", the first Tamla single, in 1959

Lacking the funds to distribute the record nationally, Gordy journeyed to New York and secured a national release for the record with United Artists; but he retained distribution rights for Tamla in Michigan. As a result, record stores and jukeboxes in Michigan featured “Come To Me” on the Tamla label while the rest of the United States saw the record on the United Artists logo. Those Tamla 45 rpm singles of “Come To Me” sold in Michigan were pressed by ARP in Owosso.

That was the beginning of a very profitable relationship between the American Record Pressing company and the tiny label that eventually bloomed into Motown Records. It was estimated that approximately 80% of ARP’s business during the next 13 years involved the stamping of vinyl records for Motown.

I made the hour-long drive to Owosso from Essexville because I was trying to find a photograph of the American Record Pressing Company for a PowerPoint presentation that was going to be part of a class I was teaching in November on the history of Motown in Michigan. I first went to the Shiawassee District Library in downtown Owosso. I was able to find the original news article from the October 30, 1972, edition of the Owosso Argus-Press on microfilm, but there were no photographs of the building before the devastating fire.  This field in Owosso was once the site of the American Record Pressing company

This field in Owosso was once the site of the American Record Pressing company

Since I also wanted to visit the site at 1810 W. King St. where the plant once stood, I took the five-minute drive from the library through town to see if there was anything left of the structure. On the way, I drove past the first location of ARP at at 1011 E. Main. The original building is long gone, and the address is now occupied by the parking area for the Owosso Walgreen's and an O'Reilly Auto Parts store.

I tried to imagine what Berry Gordy and Smokey Robinson must have been thinking in 1959 while driving through the snow to Owosso on two-laned M-21 to the original location on E. Main. To a couple of young men who had grown up and worked in Detroit, it must have seemed that the Amercian Record Pressing company was 'in the middle of nowhere’.

ARP's second location on W. King Street is now a residential area with newer, upscale homes. There was no 1810 address and no apparent sign of what once had been 60,000 square foot structure. The first house number was 1790 and the next door neighbor’s address was 1820. I went to the door of the homes to ask if the owners knew anything about the American Record Pressing Company, and if they might know where the original building might have stood.

Cynthia and Matt, the attractive young couple who owned one of the homes, were aware of the plant and said that the original building was located in their backyard and extended into the unoccupied field behind their property. Cynthia told me that her grandmother, Joan Mallery, had worked at the plant; and that she was happy to have a home in an area that had once been an important part of her grandmother's life. The couple said that when they first moved in, they had to clear out old stamping machines and lots of broken vinyl while they were putting in their backyard. Now they said that they were sorry that they hadn’t kept some of what they had thrown away.

They indicated that there were still some pieces of foundation and lots of broken vinyl in the field beyond their yard; and Cynthia and Matt gave me permission to walk back, take some photos, and also pick up any materials I might find.

Twisted metal and broken concrete are all that remain of the building that housed the American Record Pressing company

Twisted metal and broken concrete are all that remain of the building that housed the American Record Pressing company

The goldenrod and milkweed plants were waist high in the field where the remains of the American Record Pressing Company lay hidden among the buzz of insects and other small creatures that have made the site their home. There were several small piles of cement foundation and twisted, rusted metal that had once been part of a thriving business that pressed hundreds of thousands of vinyl records and helped provide a living for hundreds of people in the area.

There were small pieces of broken vinyl records mixed among the weeds, clay, and rocks that had been bulldozed to make way for the housing development some years prior. I picked up some remnants of long playing records that had already been stamped and must have been ready for shipment at the time of the fire. I wondered what had been in the grooves of these LP recordings that had lain silent, broken, and forgotten for nearly thirty-eight years.

I found it to be quite a coincidence that the fire that destroyed the American Record Pressing Company occurred the very same year that Motown closed its operation in Michigan and established its headquarters in California. There apparently was no investigation of a possible arson, but it must have been at least a possibility.

Although David Howell had assured employees and residents that ARP planned to rebuild in Owosso, there was no record of it being put into action. I’m sure that the probability of losing the Motown account, which represented the majority of American Record Pressing Company’s business, had a lot to do with the eventual decision to close the operation.

Owosso today is a pleasant little community of nearly 16,000 residents. The city is most famous for its Steam Railroading Institute and its connection with Steven Spielberg’s animated film, The Polar Express. Many older residents remember the American Record Pressing Company, but most have no idea that the plant is significant in rock and roll history because of its stamping of the first Beatles and Motown 45’s in the United States.  Broken and warped pieces of vinyl records can still be found at the former ARP site in Owosso

Broken and warped pieces of vinyl records can still be found at the former ARP site in Owosso

At the Shiawassee District Library, I spoke with the librarian who researched the story of the American Record Pressing Company that I first read on the Internet. Although she was most helpful in running copies of the news story of the fire for me from microfilm, I was disappointed to learn that she had not taken the time to either visit the site or to make an extensive search for a photo of the original structure.

Sadly, there are no historical markers or any other official recognition of Owosso’s small but interesting role in both the recording industry and the rock and roll history of Michigan. Instead, the story continues to lay buried and forgotten much like the broken vinyl in the weed-covered field on W. King Street.