American Record Pressing in Owosso, Michigan, was one of the state’s most important record producing plants during most of rock and roll’s first two decades. ARP’s legend is large. Besides pressing records for an array of major labels in the United States, the company also pressed the first Motown 45s, the first single by The Beatles to be released in America, as well as many of the records released by Michigan teen bands in the 60’s on a wide variety of small independent labels. Despite its interesting history, the story of the ARP’s ownership, its daily operation, and the mystery surrounding its untimely demise by a fire in 1972 have largely gone unreported.

This is the second installment on the MRRL site of what will eventually be a three-part series of stories about the former business. Most of the information was taken from two lengthy interviews with Jeff Mellentine who was mentored by ARP’s original owner, Norman Dufour. Mellentine not only witnessed the tragic fire but was very knowledgeable of the inner workings of the business and its financial situation.

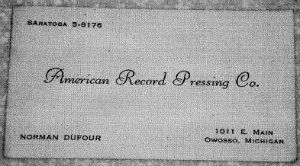

Norman Dufour's business card

Norman Dufour's business card

Norman Dufour was originally from the Stoney Point area, north of Windsor in Ontario, Canada. In the fall of 1951, Dufour purchased Vargo Records in Detroit. Vargo was a pressing plant that also issued some 78 rpm records under its own name. Dufour moved the entire operation to Owosso, Michigan, and by 1952, had changed the name of the company to American Record Pressing. Dufour and his wife Doris moved to the small city of Corunna, located about 3 miles southeast of Owosso.

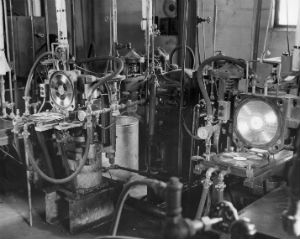

The business started with just 3 record presses in its first location at 1011 E. Main St. in Owosso. During its early days ARP only pressed 78s; and the vast majority of those orders came from customers in Detroit. For a while, ARP continued to issue some 78s under the Vargo logo, but it eventually discontinued the label and became a custom pressing operation for record companies that did not have their own pressing plants.  Record pressing equipment

Record pressing equipment

'

RCA Records first developed the 45 rpm record in 1949. 45s were composed of durable and quieter vinyl rather than the extremely fragile 78s that were made with noisy shellac. As a result of the rising popularity of 45s, ARP installed new presses to meet the demand for this latest development in recording technology. With the rise of rock and roll, 45 rpm records began to dominate the record pressing business and became ARP’s specialty product by the middle of the 1950s. Production of 78’s, on the other hand, continued to decline. The end of the era came in 1959 when the last commercially released 78 rpm singles appeared.

After a decade in Owosso, Norman Dufour’s company was shipping products to record companies all across the United States. In order to keep up with the increased demand, ARP needed to expand. To accomplish this, Dufour purchased a 22,000 foot facility on a large parcel of land at 1810 W. King Street, 2 miles west of its original location on Main Street. The building had been constructed in 1955 and was the former home of Owosso Mobile Homes, a company that had declared bankruptcy in 1962.  Owosso Mobile Homes on W. King Street

Owosso Mobile Homes on W. King Street

By early 1963, ARP installed 14 modern record presses and had its own custom label printing department at its new W. King Street location. The timing could not have been more perfect.

Besides pressing records for large nationally known labels like Cameo-Parkway, Vee Jay, and Buddah, ARP also pressed for a number of small independent labels. In addition, ARP was unique in the record pressing business in that they had their own machine shop. They could make molds, tooling, and parts; and they sold those parts to other pressing companies.

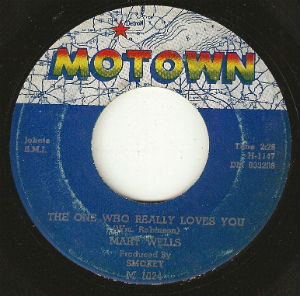

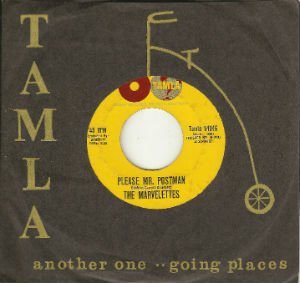

In 1959, ARP pressed the first single issued by a tiny company from Detroit called Tamla Records. It was the start of what would be a very profitable relationship. Although most small labels usually went out of business after issuing a handful of singles, Berry Gordy’s Tamla label would, within four years, grow into Motown Records, the most successful independent record label in popular music history.

This 45 rpm single of the 1962 hit "The One Who Really Love You" by Mary Wells was pressed at ARP's Main St. plant

This 45 rpm single of the 1962 hit "The One Who Really Love You" by Mary Wells was pressed at ARP's Main St. plant

Beginning in 1961, Motown began producing national hits pressed at ARP that included: “Shop Around” by The Miracles, “Please Mr. Postman” by The Marvelettes, “Do You Love Me” by The Contours, and “The One Who Really Loves You” by Mary Wells.

In 1963, Motown continued to make its mark on the Billboard Hot 100, charting such big hits as “You’ve Really Got A Hold On Me” and “Mickey’s Monkey” by The Miracles; “Pride and Joy” by Marvin Gaye; and especially “Heat Wave” by Martha & The Vandellas, a song that dominated the air waves in the late summer and early fall of the year.

Motown’s success would only increase in the next few years as hits as “Where Did Our Love Go” and “Baby Love” by The Supremes, “My Guy” by Mary Wells, “I Can’t Help Myself” by The Four Tops, “My Girl” by The Temptations, and “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” by Marvin Gaye would all top the charts. Before long, pressing records for Berry Gordy’s hit-making machine in Detroit was responsible for roughly 80% of ARP’s business.

Jeff Mellentine currently lives in Indianapolis, Indiana and has been in the record pressing business for 48 years. He grew up in a small home on the corner of Cleveland and W. King, just across the street from the second location of ARP. Mellentine was born in 1951, one of 8 children. His dad was an auto mechanic in Owosso and his mom was a housewife who spent her days raising the kids. The family was not wealthy and space was at a premium in the Mellentine family home. All the kids slept in the loft upstairs; and Jeff’s dad put in a wall to separate the boys from the girls.

It must have been exciting for a young man about to enter junior high school to live near a business that was pressing some of the big hits he was listening to on the popular Top 40 AM radio stations broadcasting from Saginaw and Flint. The only things Jeff Mellentine remembered about Owosso Mobile Homes were the two fires the building suffered during its seven-years (from 1955 to 1962) at 1810 W. King St.

Mellentine got his first job sweeping floors at ARP. Norman Dufour liked the boy’s work ethic and soon hired Mellentine to work as a gardener at his home in Corunna. Dufour and his wife married late in life and did not have any children. The Dufours used to serve lunch to Mellentine, and Norman would pick him up and drive him back home in his big Cadillac automobile. Jeff recalled that Norman loved plants around his home, and he had the area around the ARP plant on W. King completely landscaped.  ARP's second location at 1810 W. King Street in Owosso

ARP's second location at 1810 W. King Street in Owosso

Owner Norman Dufour became Jeff’s mentor. He gave a great opportunity to a poor kid from across the street by giving him the chance to learn the business from the bottom up. Dufour took Mellentine under his wing and, to a certain extent, treated him like a son. Jeff said that Dufour did that for a lot of people, and described him as “a humble man, almost saintly”. Mellentine stated that he wouldn’t be in the business today if not for Norman Dufour.

During the peak years in the 1960’s, ARP ran three shifts, 24 hours per day, six days a week. The 45’s were packed in what were called ‘popcorn boxes’ – named that because they were about the same size as the popcorn boxes that you used to get in movie theatres. There would be 25 records to a popcorn box and 4 popcorn boxes in a foot-square cardboard box (100 records to a box). All 45s were in white generic sleeves except for Motown which had its own sleeves with label names. At its peak, in the mid-to-late 60’s, ARP was producing about 3,000,000 7-inch 45 rpm records per month.

Another one of Jeff Mellentine’s early jobs was as a set-up guy on the presses – changing the stampers on the presses. Back then, the records were made manually with women most often operating the presses. Often, these women were wives from the surrounding farms, but there were single women as well. Jeff used to date a lot of young ladies who worked at ARP, and met his first wife while changing the stamper on her press.

Mellentine claimed that women ran the presses because they were more adept at it. The dexterity required seemed to suit women better than men. The women were paid by piece work. Once they completed a minimum number of records, they would earn half a cent per record and could potentially make a good deal of extra money. The guys at ARP worked in the machine shop, drove trucks, moved materials, were maintenance men, or changed the stampers as set-up men. Women working the record presses at ARP

Women working the record presses at ARP

The press operators worked at a steam table with plastic ‘biscuits’ about the width of a Graham cracker. They broke it off after it got soft, put an ‘A’ label and a ‘B’ label on a pin, put the hot plastic in the center, and then pushed a button so that the press would close and squeeze the record. Next, they would bring it out and put it in a ‘dinker’, a machine used on 45s to punch the large hole. They then pushed two buttons and the dinker would cut the center hole and cut off the excess plastic (called flash) on the outside of the disc. Both would be put into containers that would be picked up when filled. ARP would eventually regrind the flash and reuse it to make future records.

All of the pressings done at American Record Pressing had the tiny “ARP” symbol in cursive script pressed in the outer grooves. The symbol is so small that it requires a magnifying glass to see it. Mellentine claimed that it was difficult to keep up sometimes, especially on some of the big Motown 45s that were in great demand. Later on, after he had begun to move up the ladder at ARP and started wearing a white shirt to work, he got to listen to the test pressings in the ARP sound room that plant manager John Ivantis had built. Mellentine recalled that he would often get goose bumps listening to some of the new Motown releases. It would be the first time that any of these records had been heard on vinyl.

An important part of ARP’s success was its policy of delivering record orders the day after they were received at the plant. To accomplish this, orders from nearby cities like Detroit, Cleveland, and Chicago were delivered by truck and those going to cities across the country would be driven to airports and sent via air mail. It seemed that there was always an ARP truck driving records to the airports.

In the early days, Jeff and Norman often drove a company van to Flint to put records on a plane or drive to Detroit to one of the airports. Jeff gradually learned the business by working in shipping and receiving and delivering to the Motor City; and by the time he was 20-years-old, he was running the second shift at the ARP plant.

Motown singles pressed at ARP had their own custom record sleeves

Motown singles pressed at ARP had their own custom record sleeves

Mellentine tells the story that Norman Dufour would even let him drive his Cadillac on ARP business. On several occasions, Dufour had him drive his car to deliver records. The first time he did this, Jeff’s task was to bring DJ copies of the new Miracles’ single to Smokey Robinson. Mellentine was just a teenager and had yet to drive a car on his own out of Owosso, let alone to Detroit. He remembered the stares he generated when driving the Cadillac to the Sinclair gas station on Main Street, complete with its big plastic dinosaur out front, to fill up the car for the drive to the Motor City. Everyone at the station knew Jeff, and the kid pumping gas told him, “You better bring that car back where you got it or I’m calling your mom!”

These were the days before MapQuest and GPS, so Melletine had to rely on the traditional road maps for his journey. He didn’t return to the plant from Detroit until almost midnight because he got lost several times. When he finally returned to Owossso, he recalls that both Dufour and John Ivantis, and were “sweating bullets” in the ARP office, fearing that something bad had happened to him.

Aside from his interesting work experiences at ARP, Mellentine was a pretty typical teenager during the 1960s. He and his brothers were involved in a lot of street racing along the back roads of Owosso and also did some drag racing at the Tri-City Motor Speedway in Auburn, Michigan.

The Music Box - Prudenville, Michigan's teen dance club

The Music Box - Prudenville, Michigan's teen dance club

Jim Loux was one of Jeff’s close friends who also worked at ARP. He shared Mellentine’s enthusiasm for racing and his dad used to deal used cars, some of which were purchased for racing by the boys. On some weekends Mellentine, Loux, and their friends would drive north to Prudenville to attend the Music Box, located at the eastern end of Houghton Lake. It was one of northern Michigan’s coolest teen gathering places; and Mellentine described the atmosphere in the Music Box as being “a heavenly, magic world”.

Most of the time, however, they would go to dances in nearby Chesaning or at the local Owosso Armory. Oftentimes the dances would feature teen bands from the area, but they also booked major Michigan acts like Terry Knight & The Pack and the Bob Seger System, and even some national recording acts such as Gary Lewis & The Playboys. Mellentine recalled that Seger and his band played dances after basketball games at Owosso High School. Those were the days.

Like many other young Michigan men, Jim Loux was drafted into the Army and ended up serving in Vietnam. He died a decorated hero while defending a supply barge in a fire fight. In recognition of his valor, an Army supply ship was named the James A. Loux in his honor.  Owosso war hero James A. Loux

Owosso war hero James A. Loux

During the 1960s ARP was making a lot of money. ARP was mainly a 7-inch, 45 RPM record plant, and the seemingly endless supply of hit singles being produced at Motown seemed to bode well for the company’s future. The company had also been pressing 12-inch LPs for a number of years but, according to Mellentine, this was not an area of expertise for ARP. Always looking to expand their business, ARP started producing cassettes in the mid-1960s; and when cassettes didn’t sell initially, the company went into manufacturing 8-track tapes. After graduating from Owosso High School, Mellentine went to work for ARP on a full-time basis.

As the decade came to a close, however, changes were afoot in Detroit. Late in 1967, just months after rioting burned businesses and homes in the area surrounding Hitsville U.S. A., Motown’s top songwriting and record production team of Brian Holland, Lamont Dozier, and Eddie Holland left the company in a dispute over money. Their departure was a big blow to the company as the Holland-Dozier-Holland team had been responsible for most of Motown’s biggest hits during the past five years. In addition, Motown had established a second base of operations in Los Angeles, California; and not only was Berry Gordy spending more time there, but many of Motown’s popular new acts like the Jackson 5 were now recording there.

Norman Dufour owned ARP outright. He also held other interests in Nashville, Tennessee, with several other businessmen involved in the record business including United Record Pressing, located in Nashville and owned by Ovell Simkins and John Dunn.

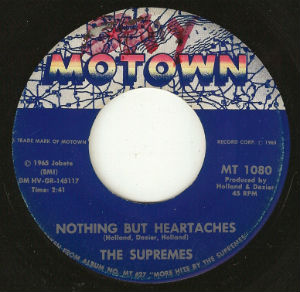

In 1969, Dufour sold American Record Pressing. The purchaser was Viewlex, a New York company that had begun a policy of acquiring other companies in the late 1960s and consolidating them under the Viewlex banner. The strategy, called roll-ups, involved aggressively buying a lot of companies at the same time. Many times the purchases were made by giving stock instead of cash, selling the business owners on the idea that they were going to make a lot of money – although this was not always the case.  Motown's most important artist during the 1960s was The Supremes. ARP pressed all of the trio's 25 Top 40 hits, including 12 that reached # 1

Motown's most important artist during the 1960s was The Supremes. ARP pressed all of the trio's 25 Top 40 hits, including 12 that reached # 1

Viewlex got started as part of a joint venture with Bell & Howell. They produced a device that would automatically advance a filmstrip in a projector when a beep sounded on an accompanying record. It was used in schools across the country. They also made camouflaged communication boxes that were dropped into the jungles of Vietnam during the war years. Besides those areas, they were deeply involved in producing the lens and other optical equipment used in planetariums across the country.

Viewlex was owned by the heads of the Peirez and Levine families, David Peirez and Leslie Levine, who Mellentine described as “scary”. In addition, the two businessmen owned Buddah Records and Bell Sound Studios in New York.

After the purchase by Viewlex, Norman Dufour remained very active in the ARP operation and continued on as the general manager of the plant. He was also a large stockholder and was on the Viewlex management committee. Sandy Wartell, founder Allentown Records that was also sold to Viewlex,was appointed the president of Viewlex. Wartell would often fly to Owosso in his twin-engine Aztec and land at the Owosso Airport to meet with Dufour.

By the dawn of the new decade, the ARP plant on W. King St. had expanded to over 60,000 square feet (three times the size of the building in 1963) and the company employed 230 people. But there were dark clouds on the horizon.

Motown moved its entire operation to Los Angeles at the end of 1971. Besides striking a blow to the heart and soul of the city of Detroit, the move also served to break up Motown’s Funk Brothers, the name given to the core of studio musicians that had played on all of the great hits produced in Studio A at Hitsville U.S. A. at 2648 West Grand Blvd.

How would Motown’s move affect ARP? Since they represented about 80% of the company’s business, ARP had good reason to worry. Furthermore, the demand for 45 rpm singles (ARP’s specialty) had begun to decline with the corresponding rise in sales importance in popular music of the LP album.  "Papa Was A Rollin' Stone" by The Temptations was one of the last Motown singles pressed at ARP before the fire

"Papa Was A Rollin' Stone" by The Temptations was one of the last Motown singles pressed at ARP before the fire

By 1972, ARP was pressing more albums than before, but according to Mellentine ARP always had problems making LPs because it was not their area of expertise. The fact that ARP was not making a quality 12-inch record was an isssue that was hurting the company by 1972. Mellentine claimed that the problem was not in the sound quality but rather in the flatness of the discs. There was often dishing or warping on the LPs, and sometimes a crackling sound that was the result of groove fill problems in the pressings.

In addition, Mellentine said that the company had begun to experience some labor unrest after the United Auto Workers union became involved with the plant. They had suffered through a nasty and sometimes violent strike that resulted in some people being arrested. When Dufour owned the plant it had been very profitable but, because of all of the above factors, things had begun to slow down and the plant was operating only five days per week by the fall of 1972.

Jeff Mellentine was married, and he and his wife had celebrated the birth of their son, Matthew, earlier in the year. He was working his way up the company ladder and was now running the night shift at the pressing plant. He had also been working on some new projects at ARP involving automating the process of making records along with John Burkett, an engineer from Nashville.

Looking back, Mellentine remembered that there were some "weird happenings" on October 29th, the evening before the fire. There was no manufacturing shift that Friday night, and there was just one security person in the building. Jeff was home with his wife and six-month-old son when got a call that night from the security guard who said he had eaten something from the vending machine that made him sick and he wanted to go home. Mellentine replied that he couldn’t give him permission because the guard worked for the security company, not ARP.

The security guard may have gone home Friday night after he called. Jeff said he wasn’t sure, but he thought it was irrelevant because the fire actually started Saturday morning while a maintenance crew was in the building. It was thought that the fire ignited around 8:00 AM or 9:00 AM Saturday morning, October 30, in the rear of the building in an area where no one was working. The security guard, if on duty, would have left at 6:00 AM or 7:00 AM – around the time that the maintenance crew came to work.

The fire at ARP October 30, 1972

The fire at ARP October 30, 1972

Jeff Mellentine was one of the first on the scene after the fire was discovered and reported to area firefighters some time shortly before 10:30 AM. Jeff got there quickly because he lived just two miles away and because his mother, who still lived across the street from ARP, had called him with the news; “Your plant is on fire!”

Mellentine said that by the time the fire trucks arrived at ARP, it was a hopeless situation. He described the scene as “an inferno”. Despite being mainly concrete and steel, the flat tar roof might have contributed greatly to the destructive blaze. He said that there was nothing the firefighters could do to save the building

Because the ARP offices were located at the front of the building, Mellentine and several other workers managed to save Norm Dufour’s safe. The accounts receivable records were in the safe so the group ran into the office as the firefighters were pouring water onto the building and pulled the safe outside. The office area was the last part of the building to burn because it was separated from the plant by a large concrete wall. The safe was the only part of ARP that survived the fire. Years later, Mellentine bought the safe and his still using it today in his current business.

Norman Dufour was in New York at the time of the fire and actually flew over the smoldering ruins in Sandy Wartell’s plane when he returned to Owosso. According to Dufour’s niece, Renee Monforton, her uncle was “devastated” by the fire that destroyed American Record Pressing.

Jeff claimed that when ARP vice president Dave Howell declared “the company will definitely rebuild” to the Owosso Argus-Press, he wasn’t really in the know. Howell was more into sales and customer relations, and while his words were reassuring, Mellentine thought that it was a no-brainer for them not to rebuild. ARP was not making much money by this time and its future prospects, especially with Motown gone, did not look promising. Besides the quality issues with their LPs, the union problems at the plant were ongoing.

Although it was apparently not reported in the Argus-Press, Mellentine said that there was an arson investigation. The investigators couldn’t find anything other than it started in the back of the building in one of the newly constructed areas, and they concluded that the fire had to do with material that was drying under some heat lamps and had inadvertently burst into flames.

Mellentine stated that after the fire there were some accusations going around Owosso. There was also a question of who had the silver bars that were stored in the plant. The silver was used in the process of making a silver nitrate solution in order to make the lacquer electro-conductive after cutting the grooves in the record making process. No trace of the silver bars was ever found in the rubble left after the fire.

Another unexplained occurrence that might have had some bearing on the fire involved Jeff Mellentine’s mother. Still living in the family home at the corner of Cleveland and W. King, she had a good view of ARP. She awoke in the early morning hours of October 30th and happened to notice a large black car driving around the building. Apparently thinking that it was not that important, she didn’t mention what she had seen that night to her son until much later. Whether or not this had anything to do with the eventual fire will never be known; and she was never interviewed by the arson investigators.

The ARP safe was the only item to survive the fire. The safe is currently being used by Jeff Mellentine's company

The ARP safe was the only item to survive the fire. The safe is currently being used by Jeff Mellentine's company

Although ARP’s main insurance carrier, US Fidelity & Guaranty, may have been suspicious of the fire’s origins it does not appear to be the reason that it took years and a lawsuit to finally get the insurance settlement. The issues in court revolved around both the cost of the equipment that ARP lost in the blaze and the value of the customer’s goods (records) that were destroyed. Another big question in the court case centered on whether ARP had enough insurance coverage at the time of the fire to deal with the catastrophic losses.

The final decision by the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York was not handed down until 1979. By that time Viewlex was in serious financial trouble and had already declared bankruptcy. The reimbursements to the customers that were listed in the court records give evidence of the effect Motown’s move to California had on ARP’s business. Of the nearly $1,000,000 in claims, only 2% went to Motown, while nearly 50% went to Budddah Records, a subsidiary of Viewlex. The days of Motown representing 80% of ARP’s business were obviously long gone by October 30, 1972.

Jeff was transferred to New York to work with Viewlex at Sonic Recording shortly after the fire. He was the only ARP employee who went to New York. His wife was unhappy living there, however, and Mellentine eventually moved back to Michigan and took a job with General Motors.

During the Viewlex bankruptcy, some of the younger members of the company who had worked their way up the corporate ladder managed to salvage some of the acquired companies including Andrews Nunnery Envelope Company, Allentown Records, Monarch Records, and changed the name of Sonic Recording to Gold Disc Records. Following the bankruptcy, the reorganized company began operating under the new name of Electrosound.

With Norman Dufour's help, Mellentine bought the ARP property back from Electrosound years after the fire. Dufour loaned him the money to make the purchase. The remains of the ARP building and its contents had been demolished and bulldozed into several large holes that were dug into the 30 acre parcel of land. The only thing that was left was a large concrete slab.

Mellentine was originally planning to build a new record pressing plant on the former ARP site. He had a few other ideas as well, but they didn’t come to fruition either, and he basically ended up only using the land for hunting. Mellentine eventually sold the land to the city of Owosso in the 1990s because he needed the money to start his own business. Owosso then sold the land to a developer who built a number of new homes on W. King Street.

Unhappy at General Motors, Mellentine went back into the record business. At the age of just 28, he left Michigan and built a replacement plant for American Record Pressing in Shelbyville, Indiana. The modern facility eventually became the # 1 record pressing plant in the country.

This silver disc of a Stevie Wonder production was presented to Norman Dufour by Motown in the 1970sNorman Dufour died in 1985. Mellentine was living in Los Angeles after leaving Electrosound and didn’t learn of Dufour’s death until the day of the funeral. He said that everyone loved Norm Dufour and he called him “a real class act”. He affectionately described him as looking “a little like the guy on the Monopoly game – short and round and he smoked big cigars. Norm was bald with some white hair but you could tell that his hair had been blond in his youth”.

This silver disc of a Stevie Wonder production was presented to Norman Dufour by Motown in the 1970sNorman Dufour died in 1985. Mellentine was living in Los Angeles after leaving Electrosound and didn’t learn of Dufour’s death until the day of the funeral. He said that everyone loved Norm Dufour and he called him “a real class act”. He affectionately described him as looking “a little like the guy on the Monopoly game – short and round and he smoked big cigars. Norm was bald with some white hair but you could tell that his hair had been blond in his youth”.

Renee Monforton, revealed that Berry Gordy attended her uncle’s funeral and that his presence meant a lot to the family. The fact that Gordy would travel all the way from California for the service is a good indicator of the high regard he had for Norman Dufour.

After leaving Electrosound, Mellentine started his own company, World Media Group, out of his home in Los Angeles. After a couple of years of outsourcing everything, he got frustrated that he didn’t have his own plant. Jeff then moved to Indianapolis, bought a house, and started working above his garage. After outsourcing for 6 months, he rented a 5,000 square foot facility for World Media Group. He bought some packaging equipment, some cassette duplicating machines and started commercially manufacturing audio cassettes. Mellentine next developed a graphic arts division and by around 1999 got into the disc making business, investing millions into clean rooms and laser cutting.

With CD sales on the decline, World Media Group has recently transitioned into other areas such as flash memory, doing BMW navigation, and also the Q system software on disc and flash for GM. Besides doing work for drug companies, direct marketing companies, and exercise and yoga materials, WMG also does all the Simon and Schuster novels, including the works of Stephen King.

The company moved out of the music business about a decade ago when Napster and other file sharing sites came along, but they still do some esoteric recording projects like Manheim Steamroller and a few European jazz artists.

In 2006, former ARP workers and their familes came together in Owosso to commemorate the record plant

In 2006, former ARP workers and their familes came together in Owosso to commemorate the record plant

Over the years, Mellentine has witnessed major changes in the music industry. He thinks that the worst thing that happened to the music business was when the real entrepreneurs of the business like Jerry Moss, Herb Alpert, Berry Gordy, and Ahmet Ertegun, individuals who loved and understood the music, were gradually replaced by corporations who were only interested in the bottom line. The concept of developing an artist was thereby replaced by the drive for instant profits.

Mellentine said that when he was a teenager, Berry Gordy would often show up at ARP. Many years later, Jeff saw Berry Gordy and Smokey Robinson at a charity event for the T. J. Martell Foundation at the Hilton in New York City. Gordy was being honored for his humanitarian works – he had donated a lot of money to AIDS, leukemia, and lymphoma research.

After the event, Mellentine approached Gordy and said, “You probably won’t remember me, but I was that snot-nosed kid who used to deliver records to you guys in Detroit.” Gordy called Smokey Robinson over to give Mellentine a hug and said, “Man, all that stuff you did for us.” It was a great evening that brought back a host of memories for all concerned of the glory days and importance of American Record Pressing in Owosso.