By Gary Johnson

At the start of the 1965-66 school year at Bay City Central High School the rules regulating the hair length of male students were strict. School administrators around the state believed that longer styles would have a negative effect on learning, and the grooming directives were very specific in regard to how long a young man's hair could be on the sides and back of his head as well as the bangs in front. When two students challenged those rules, it set off a controversy with serious repercussions.

Inspired by The Beatles, John Hale (vocals) and Tom Smith (keyboards) started playing music together while they were students at Central High. By the start of 1965, they had put together a band called The Epics, and they signed on with Bill Kehoe and Delta Promotions who began managing and booking the group – most often at Kehoe's Band Canyon teen club in Bay City. Hale and Smith would become figures of controversy during the fall of 1965, however, when the length of their hair became a disciplinary issue at school and the subject of numerous stories in the Bay City Times.

"I kind of knew Tom but we became much closer after we started playing music together," Hale recalled. "I was just the singer at that time." The Epics' first gigs were at school parties and dances, but after they won a Battle of the Bands competition at Daniel's Den in Saginaw, the group earned a cash prize and engagements to play at the popular teen club.

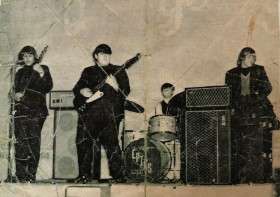

In a recent interview John Hale picked up the story. "Our bass player got drafted and Bill Kehoe, who was managing us at the time, said to me, 'Why don't you play bass'? When I told him that I didn't know how, he said 'You're gonna learn'; and that night he brought a bass guitar and amp to my house. My mother, who wasn't a music teacher but was an accomplished musician who played organ in church, sat up with me and taught me how to play the chromatic scales and I've been a bass player ever since," Hale recalled.  (L to R) Tom Smith, Mike McBride, Al Hill, and John Hale at the Alkali

(L to R) Tom Smith, Mike McBride, Al Hill, and John Hale at the Alkali

By the fall of 1965, The Epics had gone through a few lineup changes and now featured Smith on keyboards, Al Hill on lead guitar, Mike McBride on drums, and Hale on both lead vocals and bass.

Guitarist Al Hill was interviewed years later by Bill Holtzapple about his years in the Epics. "John Hale was a good front man. He was good looking and had a lot of girlfriends. He was a big attraction which is important for any band," Hill said. "The stage clothes had that English look we were going for that was so popular during the British Invasion years. Our song material was also British Invasion stuff mixed with original composition things – Tom Smith was the lyricist and I put together the tunes."

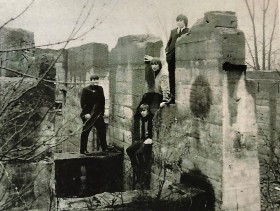

The Epics had some early publicity photos taken at the ruins of the old United Alkali Plant, a British chemical company that was built along the banks of the Saginaw River in 1898 in South Bay City and demolished in 1928. Known locally as 'The Alkali', the band liked the desolate look of the factory ruins, and it made for some atmospheric shots that evoked some of the bombed-out photos of England in the years following World War II.  The Epics at The Alkali

The Epics at The Alkali

The Beatles and the British Invasion bands that followed in their wake had not only caused a musical revolution, but also a revolution in style – especially hairstyles among young men. Many adults, including those entrusted to lead our school systems across the country, perceived this as a threat to the established order and did their best to nip this alarming trend in the bud.

In September, just prior to the start of the 1965 school year, the Bay City Times published a long article, titled Schools Rule Styles: Good Taste Is Guideline by Margaret Allison. It covered regulations for student attire at area high schools by stating: "Schools are ready for the fall battle to curb far-out student fashions. Teachers, counselors, and principals are particularly bracing themselves for an invasion of mop-headed Beatle emulators."

According to the article, long hair and tight pants were taboo at Bay City's high schools. 'Long hair' to school administrators meant locks touching the ears or shirt collar and bangs longer than two fingers above the eyebrows. "If they appear this way, students will be sent home", Bay City Central High School Principal Theodore B. Southerland informed the Bay City Times.

Bay City Superintendent Elwyn J. Bodley further instructed the newspaper and its readers: "It is suggested boys wear clean slacks or blue jeans of proper fit and sport shirts. Shirts should be buttoned from the second button down. Long shirt tails should be worn inside the trousers."

The fashion rules didn't just apply to boys, however. According to Superintendent Bodley, "Girls are not allowed to wear slacks to school. Dresses and skirts should be of an appropriate length." At Central no shorts, culottes (knee length trousers, cut with very full legs to resemble a skirt), and no extra short skirts were allowed. "Girls should refrain from wearing too much makeup and coming to school with their hair in curlers," Bodley added.

Superintendent Elwyn Bodley

Superintendent Elwyn Bodley

John Hale and Tom Smith were determined by Bay City Central administrators to be in violation of the restrictive hair length policy at the start of the school year. Hale was a 17-year-old senior and Smith, a 16-year-old sophomore. As members of The Epics, the pair played regularly at area dances and teen clubs; and Hale and Smith explained to school authorities, to no avail, that their hair styles were part of the band's image. Thus, began a haircut battle at Bay City Central that would soon result in serious consequences for the two young men.

When Hale and Smith declined the order to cut their hair, they were suspended from Bay City Central High School. Alerted to the suspension, the Bay City Times photographed Hale and Smith with the caption 'Controversial Haircuts' and put the photo on the front page of the paper. The caption included the school authorities' position that the haircuts were "inappropriate" and that it was their responsibility to establish conduct and grooming rules for students. It also included the other side of the debate in which the boys' mothers, Mrs. Marian Smith and Mrs. Martha Allen, protested the action as a civil liberty violation.

Tom Smith and John Hale in Bay City Times' photo showing their "controversial haircuts"

Tom Smith and John Hale in Bay City Times' photo showing their "controversial haircuts"

The follow-up story, Bangs Battle Grows Hotter, appeared in the Times shortly thereafter. It reported that Hale's mother, Mrs. Martha Allen, had written a letter to President Lyndon Johnson that included photos of her son. She wrote: "As you can readily see, this hair style is not a 'Beatle' or any such wild style. Even if it were one of the 'wild styles', I maintain that as an American citizen and a taxpayer who pays taxes to the school from which he was suspended, I would have the right as his parent to choose an appropriate style of hair for my son".

In the conclusion to her letter to President Johnson, Mrs. Allen stated: "This boy's father fought in the Battle of the Bulge in World War II for the 'Land of the Free and Home of the Brave'. Is this boy now violating that freedom for which his father fought? If he is, we will be glad to have his hair cut to conform with the laws of our great and wonderful country."

The news article revealed that well-meaning Central band members took up a collection to buy Smith a wig to use when he played with The Epics. "We thought this would be a way for Tom to come back to school," stated drum major Doug Hostetler. "He could have his hair cut and, with the wig, have long hair when he plays with the rock 'n roll band." Band Director Walter Cramer explained: "We thought maybe this idea might put the matter in proper perspective. The students feel that in little things like this they should conform."

The article also included a paragraph that indicated that another Bay County school, Essexville's Garber High, sent a group of boys home that week as well. The Essexville Superintendent was quoted as saying the boys were suspended "to make adjustments on their haircuts. Students and parents took care of it very peacefully," he told the newspaper.

Hale and Smith stood their ground, however. They were supported by A. J. LaMarre and Bill Kehoe, local businessmen and owners of Band Canyon where The Epics played regularly. They both agreed with the boys' position that their hair styling was part of the band's image. They, along with the boys' mothers, protested the suspensions and claimed it was a question of civil liberty. School officials, on the other hand, continued to insist it was their responsibility to establish conduct and grooming rules for students.

The Bay City Times' next story on the controversy was titled Haircut Battle Nearing Climax. It reported that both mothers wanted their sons back in school, and that Mrs. Allen, who was a circuit court reporter in Bay City, was considering making the issue a court case and was seeking legal opinions. She explained: "I have asked for the question to be researched on both sides. When I see the law, I will then know whether to litigate."

Hale's mother emphasized to the Times' reporter: "I have no intention to hurt the school. I want to know whether a right is violated. Does my son have the right to wear his hair the way he wants?" Mrs. Smith was a second grade teacher at Thomas Jefferson School in Bay City. She told the newspaper: "Hair isn't school business, but the head and heart are. I wish they would concentrate on teaching and not catching."

In the very same news article, school authorities claimed they were seeking a solution. Principal Southerland explained the need for enforcing rules, especially on hair length: "We feel that an improved teaching-learning situation will prevail if students attending senior high school are dressed and groomed in a manner appropriate to conventional business attire, including neatness and cleanliness of body and clothing."

Central Vice-Principal Paul L. Grein reported he had spoken twice over the school's public address system, explaining conduct, dress and grooming rules. He said the majority of students are complying with the regulations, both in dress and hairstyling. Other students who were asked to get their dress or hair "in order," Grein explained, have complied.

John C. Noell, principal of T. L. Handy High School, on the other hand, seemed to be digging in his heels rather than seeking a solution. "I'm responsible for the training, safety and welfare of approximately 2,000 students for six hours a day. If I have this responsibility, I must also have the right to make some judgements, and I'm going to make these judgements as long as I am charged with the responsibility."

"We expect good grooming," Noell stated, "and when I look down the hallway, I want to see at an instant glance whether I am looking at a boy or a girl". In his exaggeration Noell conveniently omitted the fact that girls were pretty easy to pick out in the hallways since they were required to wear skirts.

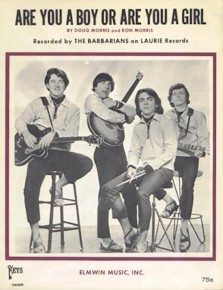

The Barbarians

The Barbarians

Coincidentally, those quotes from the Handy principal were uttered the very same week that a garage-rock band from Provincetown, Massachusetts, called The Barbarians debuted on Billboard's Hot 100 with a catchy tune called "Are You a Boy or Are You a Girl". The song served as a slice of humorous social commentary with lyrics that posed the question plaguing adults across the country when they saw a boy with long hair: "Are you a boy? Or are you A girl? With your long blond hair, you look like a girl. Yeah you look like a girl. You may be a boy, hey, you look like a girl." Listen to "Are You A Boy Or Are You A Girl" by The Barbarians: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sj8UxrnIcMM

Although time has proven Hale and Smith to have been on the right side of a controversy that may seem trivial today, the public debate over long hair on males was one that raged all across America in the late 1960s. Like the "bangs battle" in Bay City, these fights were over individual choice, authority, and definitions of masculinity.

In all, over one hundred "hair cases" were appealed to the federal courts in the United States and nine of these were appealed all the way to the Supreme Court, which side-stepped the issue again and again. One of these cases appealed to the Supreme Court involved three members of a Texas band who were suspended from school because of their Beatles-like hairstyles. The boys lost at the appeals level and took the case to the Supreme Court, which refused to hear it, meaning the earlier decision stood.

On September 30, the Bay City Times published Hair Style Dispute Still Under Way. It reported that a threatened noon "walkout" at Bay City Central in support of Hale and Smith failed to materialize. The newspaper referred to demonstrators as "longhairs protesting school authorities' edict against what they called inappropriate hair styles."

"Rumors of the walkout were rampant around the school, and teachers were reminding students of their responsibilities," according to the newspaper report, which also included the titillating news that "Girls were reported protesting school authorities' decisions on skirt lengths."

The Bay City Times' story went on to report that, during the previous evening, groups of students were carrying self-made cardboard signs bearing such legends as "The Beatles have hair and they are millionaires", "Our hair's fair, the teachers aren't", and "Civil Liberty". Referring to the students as "bangs-wearing pickets", the newspaper wrote that they were protesting not only the edict against long haircuts but also the suspension of two Bay City Central students, Tom Smith and John Hale. Meanwhile, school officials were quoted as saying: "Schools should set standards that lead to proper behavior."

Michael Cook was a freshman at Bay City Central at the time. He played in a popular teen band called The Intruders. In a recent interview he stated, "I felt the rules were crazy but I didn't grow my hair long enough to get in trouble. I was in the school orchestra with Tom Smith before he was kicked out of school. Tom played the coronet and was almost a musical prodigy – really, really good."

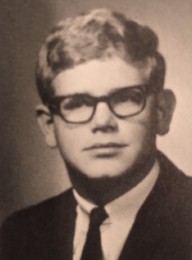

Cook also described the student reaction at Central: "They were outraged and really behind Hale and Smith's protest of not cutting their hair. It was the beginning of the generation of change. That was where everybody's head was at – at least what I remember."  Bruce Sherbeck 1965

Bruce Sherbeck 1965

Bruce Sherbeck was a member of The Vibrations, a teen band that also appeared at Band Canyon. He was in the senior class at Bay City Central with John Hale and a member of the school band with Tom Smith. In a recent interview he clearly remembered the hair controversy: "Hale was very popular and Smith was a fabulous musician," Sherbeck said. "Tom played coronet in the school band and was first chair as a freshman."

Because Sherbeck took drum lessons at the Smith home from Geoff Smith, Tom's older brother, he was closer to the situation than most. "Tom's mother, Marian, had a tough time during the hair controversy. Her husband had left her and the publicity and negative comments from the hair issue were hurtful," Sherbeck recalled. "She was not happy with the Bay City school system. The school wanted you to toe the line – that was the policy."

Diane Osterhout was a senior at T. L. Handy High School and John Hale's steady girlfriend during that turbulent school year. The couple had met at White's Drive-In on Euclid Avenue, one of Bay City's most popular teen gathering places in the 1960s. "The kids at Handy were on John and Tom's side," Diane recalled in a recent interview. "They liked that they were in a popular band and they liked their hairstyles. My mother didn't like John but I didn't care. He was a bit of a rebel, but he was a nice guy and I enjoyed going out with him."  Diane Osterhout 1965

Diane Osterhout 1965

Although Hale and Smith had plenty of supporters among like-minded teens, it's probably fair to say the vast majority of Bay City's population in 1965 supported the schools' position. Long hair styles on young men in school were not readily accepted, and the majority of the population supported the upholding of tradition and the authority of adults running schools over Hale and Smith's desire for individual freedom. Unfortunately, that support was sometimes expressed directly to the boys and their families via rude and nasty comments.

Hale recalled that there were insults and verbal abuse outside of school, but he claimed that he didn't take any of it personally. "It was just who I was and still am," he said.

Diane Osterhout witnessed some of the negativity firsthand. "John kept a pretty even keel as far as the comments about his hair length," she said. "He didn't care what other people thought and he still doesn't to this day. I was so crazy about him that I wouldn't have cared what anybody said; I would have stuck up for him."

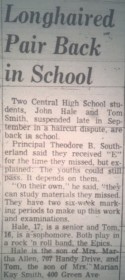

The final Bay City Times' story on the controversy, Longhaired Pair Back in School, seemed to indicate that the issue had finally been settled, and it reported that Hale and Smith had been allowed back into Bay City Central. Principal Theodore Southerland indicated that the pair both received "E" for the time they missed. "The youths could still pass," he explained, "It depends on them. On their own they can study the materials they missed," he told the newspaper. "They have two six-week marking periods to make up this work and examinations."

What Southerland failed to mention, however, was the fact that Bay City Central still expected Hale and Smith to get their hair cut to a length deemed acceptable to the administration. Hale claimed that he wasn't sure why he and Smith were allowed back in school, but it might have had to do with the fact that their mothers decided to not take the issue to court. School officials were not going to budge on the grooming requirements; and Hale and Smith ended up being expelled for the remainder of the school year when their hair was again deemed to be too long.

The Epics continued to play during the controversy, appearing regularly at Band Canyon in Bay City and at teen dances all around the state including Northern Michigan locales such as the Peppermint Lounge in Sault Ste. Marie, the Tanz Haus near Traverse City, and a second Band Canyon in Cheboygan.

The Epics at Band Canyon

The Epics at Band Canyon

Following a November performance at Daniel's Den in Saginaw, The Epics were featured in Deb & Jo's weekly teen music column in the Saginaw News under the headline: 'Bay City Lads Produce Bold Sound'. The article stated that The Epics were regulars at Band Canyon and mentioned a possible tour for the band in the summer. It also included some of the songs performed by The Epics at that time: covers of "Louie, Louie", "Annie Fanny", and "Donna" as well as band originals including "Baby Don't Cry" and "You're Doin' Fine".

Although The Epics failed to release any vinyl recordings, guitarist Al Hill revealed to an interviewer years later that the band produced acetates of some original songs at the Schiell Recording Studio in Bay City. Hill said that The Epics could never agree on a recording contract with Bill Kehoe, who owned and operated the Deltron label in Bay City, and that the acetates had been lost over time.

Hale introduced Diane Osterhout to A. J. LaMarre, who served as the on-site manager at Band Canyon, in 1965. LaMarre liked Diane, and she started working there selling tickets. "It was so much fun there," she recalled. "They had a lot of great entertainment and the young bands were just starting out. When The Epics played people were always out there dancing. I just have good memories of Band Canyon, and I think it was a wonderful place for teenagers. I wish kids had that today."  Band Canyon matchbook

Band Canyon matchbook

"My sister Gail was three years younger, and she went to Band Canyon when it first opened up in 1965," Diane said. "She was underage and she would stand outside with her girlfriends and ask guys to walk her inside. You could get into Band Canyon if you were underage if you were brought in as a date – or in her case a pretend date."

"I was attracted to Band Canyon because I was a little older and the school dances were getting kind of boring," Diane recalled. "The gossip room was fun to sit and talk with friends, but most of the time I was dancing or watching the bands – I wasn't much of a sitter," she said. "I loved to dance and they had a big dance floor and live bands; and of course, my boyfriend played in a band which was fun."

Although John Hale was very popular at area teen clubs like Band Canyon, he was persona non grata to Bay City public school officials. This became glaringly apparent when Diane Osterhout invited Hale to her senior prom at T. L. Handy High in the spring of 1966. In order to bring a guest, Diane had to go to the office of the Dean of Students, Marshall McCuen, to get permission and a signed slip for her date

Marshall McCuen T. L. Handy High School

Marshall McCuen T. L. Handy High School

McCuen signed the slip and Diane purchased her prom dress at Sempliner's in Bay City. When she arrived at the prom with Hale, however, they were confronted by McCuen. "He said, 'I didn't know you were going to bring him.'" Diane recalled. "I said, 'You signed the slip' and he replied, 'You have to leave immediately'".

It's difficult to imagine how McCuen thought his action was justifiable or fair; and Diane said that he kicked them out of the prom so quickly that most of the other attendees didn't realize that they'd been denied entry to the dance. She also revealed that McCuen did not show even a sliver of empathy afterwards. He never took the time to speak with her at school to explain his decision to oust them after signing the permission slip or even acknowledge the embarrassment and disappointment that resulted from his actions.

John Hale and Tom Smith did not back down in the "battle of the bangs" at Bay City Central but they paid a hefty price. Hale did not graduate with his class in June of 1966, although his senior photo was somehow included the Centralia yearbook. Smith was unable complete his sophomore year and would not return to the school in the future. According to Hale, he and Smith missed over six months of classes due to suspension and expulsion over the hair issue during the school year. Both young men went on to earn General Equivalency Degrees.

After leaving the Epics,Tom Smith went on to form a musical duo called Tomcat with Cheryl Ferrio. The pair played in small Michigan clubs and Holiday Inns before meeting Harry Chapin at a concert at Delta College. Encouraged by Chapin, the duo went to New York in 1975 where they were mentored by the singer and possibly did some recording. According to his friend Joe JamrogTomcat opened for Chapin when he appeared at Pine Knob in Clarkston, Michigan.

Joe Jamrog’s connection to the local music scene was through Tom Smith and his band The Epics. He first met Bill Kehoe at Band

Canyon where he would often help carry The Epics’ equipment for their regular gigs there.

After getting a taste of the local rock and roll scene, Jamrog left his job at Steering Gear to pursue work in the music business. Kehoe hired him to be road manager of a group of musicians that he falsely billed as The Archies’. Jamrog’s job came to an abrupt end, however, after Kehoe closed down Delta Promotions under the threat of lawsuits. His scheme to put several imposter bands on the road, including two different groups impersonating The Zombies, was exposed by Rolling Stone magazine.

No one seems certain as to why Tomcat broke up. In a newspaper article in the Bay City Times, Smith indicated that he was turned off by some of the things he witnessed in New York, but according to his friend Joe Jamrog, Tomcat ended when Ferrio decided to leave the duo. Smith returned to Bay City and married for the third time. He and his schoolteacher wife raised three children before his untimley death from cancer in 1992.

The teenage romance between John Hale and Diane Osterhout came to an end in 1967 as did his association with The Epics. He didn’t stay in contact with Kehoe, especially after the Fake Zombies debacle in Rolling Stone. "I found it distasteful," Hale said in a phone interview in 2021. "I got to know Dusty Hill and Frank Beard when they were working with Kehoe. I didn’t see them perform as 'The Zombies'," but I did hear them play at Delta Promotions."

Hale moved to Montana at the end of the decade and began a 25-year career in the motion picture industry as a grip, the person responsible for positioning a production’s cameras and support equipment. He said that his career as a grip started in Oak Creek, Montana, on a movie called Amazing Grace and Chuck. “I got involved with the crew on that and then did some movies with them in New Mexico and got hired in Florida by Bert Reynolds and worked for him for three years, mostly on a TV series called B.L.Stryker,” Hale recalled. “Then I did a few more movies in Florida before I went to Hollywood and joined the Grips Local 80.”

Hale continued to play bass and sing until 2017 in a country rock band called The Buffalo Chips. The group played all the major ski resorts, once toured with the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, and recorded two albums containing many of Hale’s original songs.

In 2022, John’s wife Joan posted that he had passed away peacefully surrounded by family at his ranch in Montana. He had been suffering from dementia.