When Michigan native Chuck Daugherty was growing up, radio was a big box in nearly every home around which the family gathered to listen to their favorite entertainment programs. There were comedy shows like Amos ‘n’ Andy or the thrilling saga of The Lone Ranger. You could listen to live music on Benny Goodman’s Camel Caravan, enjoy variety programs such as The Andrews Sisters Show, and corral the kids with fare like Tarzan and Little Orphan Annie.

By the dawn of the Rock and Roll era nearly all of those programs were gone because of television. In Rockin’ Down The Dial, David Carson’s history of Detroit radio, he states that “Across America, radio had survived by reinventing itself and, with few exceptions, had become the land of records, news, and the announcers who personalized their style and became the medium’s new stars: the disc jockeys.”

Chuck Daugherty

Chuck Daugherty

Although he is mentioned just once in Carson’s book and his name is usually omitted in the listings of the most famous or influential DJs of Rock and Roll’s first decade, Chuck Daugherty’s on-air charisma and pizzazz enabled him to become one of those stars in both Michigan and California.

Charles “Chuck” Daugherty was born on August 4, 1930 in Kalamazoo, MI. During the Great Depression, Chuck took advantage of the theater programs that were part of the Works Progress Administration, one of the main components of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. Daugherty acted in numerous productions in the city’s Children’s Theater program that was housed at the Civic Theatre in Kalamazoo. Chuck earned an actor’s equity card while still a teenager and joined a repertory (stock) company that ended up constructing, and then performing at, the Barn Theater in Augusta, Michigan.

Daugherty got involved in radio as a teenager by hanging around local station WKZO. He did not attend broadcasting school – there was no such thing at the time. Always interested in music, he taught himself to play the harmonica. Chuck was good enough on the instrument to eventually make a recording with the Kalamazoo hillbilly band, Rem Wall and His Green Valley Boys. The band had a weekly radio program on WKZO and also appeared on a Friday night television show called the Green Valley Jamboree for over 34 years in the Kalamazoo area.

In 1947, Daugherty was a guest soloist playing Ravel’s “Bolero” on Edgar Bergen’s radio program on NBC. Bergen did his show from his home located west of Kalamazoo. Chuck then entered and won a talent contest with his harmonica at radio station WGFG and his prize was the opportunity to make a 78 rpm recordings of “Claire De Lune” and “Begin The Beguine” with the NBC concert orchestra.

In the late 1940’s Daugherty enrolled in Kalamazoo College with a major in music. He played trombone in the Kalamazoo Symphony Orchestra while he was in school.

Daugherty was now married and when his wife became pregnant during his junior year, he quit college and began looking for a full-time job. Chuck had done some announcing at his college radio station and auditioned for an opening at WGDF in Grand Rapids.

While at WGDF, Daugherty met Milton Crandall, a flamboyant promotion man whose publicity stunts first earned press coverage during Hollywood’s silent film era. Crandall, who had a knack for capturing the public’s imagination, gained national attention for his publicity stunt for the 1922 film, Down To The Sea In Ships, a whaling drama that starred actress Clara Bow.

To generate press for the picture, he tipped the Denver newspapers that a whale had been sighted on Pike’s Peak, a 14,000-foot-high mountain in Colorado. When reporters raced up to see the whale, it turned out to be a model with Crandall inside shooting sprays of seltzer water out of its top while hundreds of paid spectators shouted ‘Thar she blows!’

Crandall, who also promoted the nation’s largest marathon dancing competition titled “The Dance Derby of the Century” at Madison Square Garden in 1928, took a liking to young Chuck and gave him some valuable advice; “The secret to getting ahead of the pack in a competitive market is that you have to be different”. As we shall see, Daugherty would later take Crandall’s counsel to heart in the promotion of his radio programs. .jpg) Chuck at ABC station WXYZ

Chuck at ABC station WXYZ

Less than two years later in 1953, Chuck had moved to ABC and was doing coast to coast work as an announcer at WXYZ out of Detroit. He was the announcer, and sometimes an actor, on two of the most popular radio shows produced in Detroit; The Lone Ranger and Sergeant Preston of the Yukon.

He also hosted several live music programs in the Motor City including Rhythm On Parade, an all-black show broadcast on Saturday evenings from the Flame Show Bar that featured visiting black recording stars such Billie Holiday, Dinah Washington, Billy Eckstine, Sarah Vaughan, and Nat “King” Cole.

Chuck got into spinning records in the afternoon as a DJ at WXYZ in 1958 after the station lost its two most popular on-air personalities, Ed McKenzie and Mickey Shorr. Because of his growing popularity, Texaco requested that Daugherty host an all-night radio program in Detroit that could be a pilot for a national show if it was successful. The program was called The All Night Satellite and ran from midnight to 6:00 a.m.

Although on the surface it seemed to have little chance of success, Detroit was a three-shift industrial city with lots of workers anxious for something to listen to in the middle of the night. There was also an army of teenagers with transistor radios next to their ear in bed secretly digging the latest sounds while their parents thought them asleep.

Chuck did his own news segments on the show and interviewed various Texaco station managers during the program about any specials that were being offered in between a steady diet of Rock and Roll and a variety of weird outer space sound effects. The All Night Satellite quickly became the # 1 WXYZ radio program and a big hit with the younger listeners.  Chuck - I'm a Moon Goon

Chuck - I'm a Moon Goon

One of Chuck’s most popular promotions on the show was the “moon goons”. Daugherty came up with the idea of promoting his show with ‘I’m a moon goon’ buttons. The buttons became a very popular item among Detroit teens and could be seen on jackets, sweaters, and blouses all over the city. Thousands of the buttons were given away at Chuck’s DJ dances held at local armories, roller rinks, and amusement parks.

Daugherty was one of the earliest radio personalities to host record hops in Michigan. It started when a Detroit high school called WXYZ and requested a DJ to play records at one of their dances. The station asked Chuck to do it, and then provided him with an engineer and equipment since there were no portable DJ units at that time.

The word spread, and Chuck quickly became Detroit’s most popular host at teen dances in Metro Detroit as well as in Walled Lake, MI. Daugherty would bring many of Detroit’s early Rock and Roll artists including Jack Scott, Jamie Coe, and The Royaltones to the hops to sing and play along with their records. The dances got so popular that Daugherty also began booking national recording artists from New York.

Chuck was an amateur magician and learned hypnosis while he was studying sociology at Kalamazoo College. Always the showman, he would find ways to incorporate both at the dances. Daugherty would also bring stuffed animals to the hops and then give them away as prizes throughout the night. In order to win, teens would have to compete in some zany contest such as the first girl to come up to the bandstand with her boyfriend’s socks on her hands or the first to come up wearing his necktie knotted backwards

In 1959, Coca Cola came to WXYZ with a radio show concept called the Hi Fi Club, a half-hour program that ran from 7:30 to 8:00 p.m. on Tuesday and Thursday evenings. It was aimed at teenagers and Daugherty was the logical choice to host it. The program was broadcast in the top ten markets across the U.S.  Chuck's All Night Satellite card

Chuck's All Night Satellite card

Chuck’s All Night Satellite show used a tight Top 40 playlist. It was difficult to place a new record on the show and even more difficult if you were on an independent black-owned record label. But Coca Cola’s Hi Fi Club show gave the DJ a lot more latitude in choosing what to play if he thought it was something the targeted teenage audience wanted to hear.

Chuck was doing the program from a Chevrolet dealership’s showroom in Roseville, Michigan. One night Daugherty was approached before a show by a young record promotion man named Al Abrams with a record by Barrett Strong on Tamla Records, a small Detroit label.

The song was “Money” and after taking the record home to listen to it, Chuck arranged for Abrams to bring Strong to the next show for an interview and to debut the song on the air in a segment called “Make it or Break it”. The positive response of the listening audience was immediate, and Chuck played the song a few more times on the show. Bolstered by the hundreds of calls, “Money” was added to WXYZ’s playlist.

The upshot of the exposure on the Hi Fi Club was in a surge in Detroit-area record sales for “Money”, and the song quickly entered the playlists of other Detroit stations as well as radio stations across the country. Because Berry Gordy did not have enough money at this time to distribute “Money” nationally, the record was released on his sister Gwen’s Anna label which had a national distribution deal with Chess Records.  The Hi Fi Club

The Hi Fi Club

Daugherty’s decision to present “Money” on his Hi Fi Club program helped the song become Gordy’s biggest hit yet for his tiny company, reaching #23 on Billboard’s Hot 100 and peaking at # 2 on Billboard’s R&B Chart in 1960. As a result of its success, Gordy took the plunge and began distributing his own records later that same year. It was an important step in the growth of a small Detroit company that would soon become known around the world as Motown.

Chuck and Berry Gordy became friends and Daugherty was a frequent visitor to Gordy’s new base of operations at Hitsville U.S.A. on West Grand Boulevard. Chuck had long been an avid photographer and by this time had his own small studio in Detroit. He shot and developed all of the early publicity photos of Motown’s artists free of charge. In exchange, Gordy and Abrams would assist Daugherty whenever they could.

One example is when they recruited three young Motown employees to help Chuck move from Grosse Pointe to Novi. The helpers turned out to be the Holland brothers, Brian and Eddie, along with their friend Lamont Dozier. This was a couple of years before the trio of Holland, Dozier, and Holland began writing and producing a bevy of hits for Motown.

Chuck also had the distinction of subbing for Dick Clark as host of American Bandstand. They had first met when Clark had visited Detroit. Daugherty was recruited as a replacement for Clark when he was out on the road with his Caravan of Stars tour. Daugherty would later host his own televised dance program in California.  Chuck with Dick Clark

Chuck with Dick Clark

Daugherty left Detroit at the height of his popularity because of the decision of WXYZ’s new management to bring its own team of announcers to the station. Chuck could see the handwriting on the wall, and he left WXYZ to join WQTE, a small station in Monroe, MI. His stay in Monroe was brief, however, and when his first marriage ended, he took advantage of an opening in California at a 50,000 watt station in Los Angeles.

In our interview for this story, Chuck claimed that although he broke a lot of big hits in California including “Alley-Oop” by The Hollywood Argyles on Lute Records, he did not take any payola. The record company did show its appreciation by providing a driver to squire Chuck around Los Angeles when he first moved to California. The driver turned out to be Michigan native Sonny Bono who was then working for the Lute label. These were the days before Sonny met Cher.

After moving to San Bernadino for a job at KFXM, Chuck created a stir by breaking the world’s drum-playing record to promote his new show. He played drums non-stop for over 101 hours for the promotion. This included wearing a set of bongos around his neck so that he could keep playing while he was eating and even when he was using the restroom.

In another of his San Bernadino promotions, he announced on the air that he would dye his hair green if 2,000 teens would attend one of his hops. They did and Daugherty dyed his hair, but in the process Chuck discovered that he first had to dye his hair blond before he could dye it green. This, of course, extended the life of stunt and helped make the wacky promotion even more effective.

It was at his large gatherings in California that Chuck’s antics would soon make him even more renowned. His tour de force might have the day he urged the teens listening to his show to gather at Mission Beach for a grunion run. The grunion is a small fish similar to smelt that spawn on California beaches. Daugherty was such a powerful influence that thousands of kids showed up at Mission Beach resulting in a clash with police that was described in the press as a “Disc Jockey Riot”.

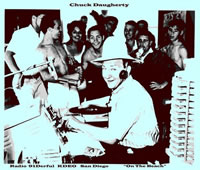

Never one to let a promotional opportunity pass him by, Chuck arranged for the station manager to fire him on the air. This would get the station off the hook for the fracas and help turn Daugherty into a sympathetic victim. The plan worked to perfection as his firing resulted in picketing by kids and adults at both the radio station and city hall to get Daugherty hired back. After a few days to build up the suspense, Chuck returned to the air and his ratings grew accordingly. Milton Crandall would have been proud.  Chuck - On The Beach San Diego

Chuck - On The Beach San Diego

Chuck’s next stop was at station KDEO and he quickly became a celebrity in San Diego for his morning show which would start off each day with Daugherty bellowing “Good Morning San Diego!” Chuck also started something called the “KDEO Kooks” to promote his morning show. Each day he would announce a goofy instruction for the “Kooks” to follow. It could be to wear one tennis shoe and one dress shoe to work, or go to your job today with your tie on backwards. Strangely enough, it caught on and became a trendy thing to do. The station even garnered nationwide publicity when they were sued by a man who was fired from his job for following one of Chuck’s instructions.

One of his most popular promotions in San Diego was called “Party Crashers”. Daugherty would encourage his listeners to let him know if they were having a party on the weekend. Chuck would then secretly pick several locations and then show up unannounced to “crash” the party. Chuck would bring along chips and cokes, play ping pong with the kids, spin a few records, and then head out to “crash” another party.

Daugherty was at the forefront of the rise of the popularity of surf music in California. His Friday night dances in Riverside and Saturday night dances in Balboa, next to the Pacific Ocean, frequently used an outstanding band called Dick Dale and The Del-Tones. Dale’s unique guitar style set the bar for surf-rock and his presence at Chuck’s dances drew thousands of teens including a young band from Hawthorne, California, who called themselves The Pendletones.

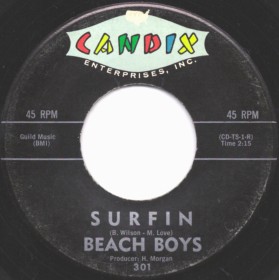

The Pendletones would pester Daugherty at the dances to allow them to play during the breaks in Dick Dale and The Del-Tones’ sets. Chuck finally gave in and he and Dale let the young band take the stage. Although Daugherty wasn’t that impressed with their playing, he immediately recognized the group’s vocal abilities.  Beach Boys' first single

Beach Boys' first single

Daugherty helped them get signed to a small Los Angeles label called Candix. The group’s first record, “Surfin’”, was released as the Beach Boys, a name thought up by the band’s new record company and put on the single without their knowledge. All was forgiven when the song was a minor hit, however, peaking at # 75 on Billboard’s Hot 100 early in 1962.

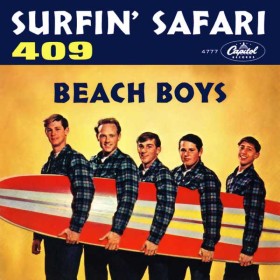

When the Candix label went bankrupt later that year, Daugherty used his contacts to help get the band an audition with Capitol Records. The Beach Boys released their debut Capitol single, “Surfin’ Safari” during the summer. It became the group’s first big hit in the early fall of ’62 bolstered by its heavy rotation on Chuck’s radio show.  "Surfin' Safari" 45

"Surfin' Safari" 45

If all this wasn’t enough, Daugherty also started the Southern California School of Radio and Television Arts and Sciences in San Diego in 1964. Chuck wrote the curriculum and hired disc jockeys to teach the courses. He advertised his school on his own show and it became nationally known in just a few years.

In 1966, however, Chuck left California and came back to Michigan. His ex-wife was not letting his kids visit him in California as regularly as he would have liked, and he wanted to spend more time with them.

Upon his return, he discovered that Michigan radio was at least two years behind what was happening in California. Michigan stations had not yet adopted the Bill Drake Format that had transformed California radio. Daugherty peddled ideas for an all-news format at WWJ and an all-oldies format at CKLW but was turned down.

Instead of trying to reinvent the wheel as a Top 40 DJ, Chuck turned to doing voice work with advertising agencies in New York and California. He also worked part-time in television at Detroit’s Channel 7 doing voice-overs and commercials.

One company that did listen to his new ideas was Playboy. After returning to Detroit, Daugherty suggested that Detroit’s Playboy Club incorporate a dance floor. Chuck then trained the Playboy bunnies to be in-house DJs. His concept was soon adopted by the other Playboy Clubs across the country.

In 1972, he opened his own ad agency called Daugherty Creative Advertising or DCA. His business attracted a diverse mix of clients including Boblo Island, Marathon Oil, the G. E. Automotive Division, Frank’s Nurseries, and the Detroit Red Wings. At its peak, DCA employed 30 people and generated over $50 million in billing.

After closing Daugherty Creative Advertising in 1983, Chuck began developing a very ambitious project called National Broadcast Productions. His goal was to put together a network of AM stations and then bring back the golden age of radio with a series of new live radio programs broadcast from Cyprus Gardens and Hollywood that would be carried by the network of AM stations. Despite the fact that he had lined up talent the caliber of Steve Allen, Jonathon Winters, Red Skelton, and even Walter Cronkite, the project failed to get enough sponsorship to get it off the ground. Prospective sponsors felt that live radio would not appeal to the all-important 18 to 40 year-old demographic.

In 1991, Chuck purchased WBCM, the former Bay City AM station. It had been operating in recent years as WUMI, a religious channel located on Bay Road in Saginaw. Daugherty and his partner changed it to WMAX, and it became an all-news channel. After his partner decided to change the format in 1994, Chuck sold his share of the station and spent the rest of the decade serving on a cable television commission and as a chairman of the board of the symphony orchestra in Warren, Michigan.

Chuck Daugherty currently lives in Shelby Township with Judy, his wife for the past thirty-eight years. He won’t admit to being retired, and he seems as energetic as ever. When we met for the interview in Frankenmuth, he told me that “I can’t believe that I’m going to turn 80 this summer”.

Daugherty still loves music and he recently finished composing a ballet suite based on the story of the “Trail Of Tears”. Chuck also combines his love of photography with the computer to create a unique style of digital art. He says that pictures will sometimes suggest things to him. He then transforms photographs or his own oil paintings using his wife’s Adobe Photoshop program.

During our long interview, which included dinner, Chuck told me that he had no interest in writing a book about his career; but when pressed, he said that if he ever did, he might call it So You Want To Be A Star. Chuck said that he found out firsthand what it was like to be a star in his profession and also how fleeting that stardom can be.

With the days of being asked for his autograph long gone, Daugherty said he now realizes how short the public’s memory is and that whatever a person did to garner that attention can disappear quickly. Be that as it may, I’m happy that he took the time to share and, in effect, preserve some of his career highlights with MRRL.