“They gave him ten for two, what else can Judge Columbo do” – John Lennon

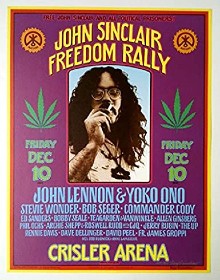

On December 10, 1971, fifteen thousand people filled Crisler Arena on the University of Michigan campus in Ann Arbor for the Free John Sinclair Rally to protest the harsh ten-year prison sentence he was currently serving for offering two marijuana joints to an undercover policewoman. Although almost everyone in attendance was supportive of Sinclair’s plight, the main reason for the overflow crowd was the promised appearance of John Lennon and Yoko Ono.

Lennon had not performed in Michigan since the Beatles had played here August 13, 1966, at Olympia Stadium. Always the most outspoken and controversial member of the band, during the late 60’s he had used his fame to speak out on a number of important issues including the war in Vietnam, women’s rights, and the political situation in Northern Ireland.

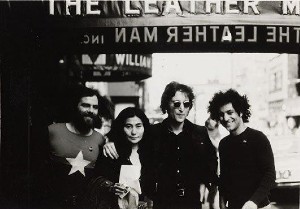

“Give Peace A Chance” and “Imagine” had not only become been chart-topping hits for Lennon, but the songs had also become anthems for the world-wide anti-war movement. This led to John and Yoko meeting with Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, co-leaders of the Youth International Party, or “Yippies”, the organization behind many of the headline-grabbing marches and rallies causing disruptions in various parts of the country. Both men had stood trial with the so-called Chicago Seven following the infamous 1968 Democratic Convention and had become counterculture celebrities.  Jerry Rubin, Yoko Ono, John Lennon, Abbie Hoffman

Jerry Rubin, Yoko Ono, John Lennon, Abbie Hoffman

The absurdist humor and showmanship demonstrated by Hoffman and Rubin in such stunts as the scattering of dollar bills onto the floor of the New York Stock Exchange and then filming the resulting frenzy of grabbing was the type of performance art that appealed to Lennon and Ono. Calling themselves the Rock Liberation Front, the twosome first joined Rubin and David Peel in sending a letter to the Village Voice on December 2, 1971, protesting against a recent attack on Bob Dylan in its pages by a writer named A. J. Weberman.

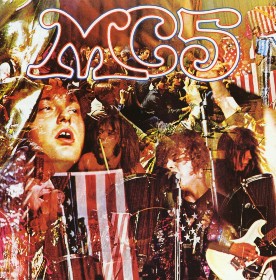

A week later at the suggestion of Rubin, John and Yoko agreed to take part in a benefit rally and concert for John Sinclair, the manager of the confrontational Detroit rock band MC5 and the political organizer of the White Panther party, a student/hippie equivalent of the ghetto-based Black Panthers. Lennon had been the target of a marijuana bust in England in 1968 and saw Sinclair’s fate as more evidence of the establishment’s use of drug laws to hound its enemies.

Lennon even composed a song for the event. “John Sinclair” was a simple country blues number and Lennon accompanied himself on Dobro at the rally in Ann Arbor:

Won’t you care for John Sinclair

In the stir for breathing air

Let him be, set him free

Let him be like you and me”…

The rally featured a host of speakers including Rubin, Bobby Seale of the Black Panthers, Ed Sanders, poet Allen Ginsberg, Rennie Davis, Leni Sinclair, and radical priest Father James Groppi. The speeches were interspersed with performances from nationally known musical acts like folksinger Phil Ochs and jazz artist Archie Shepp along with an impressive list of Michigan artists: Bob Seger playing with Teegarden and Van Winkle, The Up, Commander Cody And His Lost Planet Airmen, and a surprise set from Stevie Wonder. December 10, 1971

December 10, 1971

The event also included a live telephone hookup with John Sinclair from his cell in Jackson state prison, but the highlight of the evening was John Lennon’s twenty-minute acoustic set. Unfortunately, Lennon and Yoko Ono did not take the stage until 3:00 a.m. For the thousands who waited, it would be the last time that John Lennon would ever appear in Michigan.

The success of the Ann Arbor concert inspired Lennon to plan a nation-wide protest tour, possibly including Bob Dylan, that would culminate outside the Republican Party’s National Convention where Richard Nixon would be nominated as his party’s choice for a second term as president. Instead, his participation at the Sinclair rally and the planned tour hardened the Nixon administration’s dislike of Lennon, and he found himself under intense F.B.I. surveillance and the very real threat of deportation. As a result, the anti-Nixon tour was cancelled, and the former Beatle would spend the next five years waging a legal battle to stay in the United States. Lennon eventually triumphed and was granted his “green card” in 1976, but he was tragically shot to death by a deranged gunman outside his apartment in New York City in 1980.

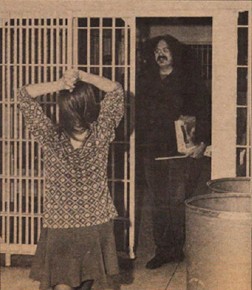

To the amazement of everyone who attended the December 10th rally, the authorities released Sinclair three days later; just 27 months into his sentence. The move was prompted by a bill passed by the Michigan State Senate just prior to the concert that drastically reduced penalties for marijuana possession, but there was no doubt that the song and the extraordinary power of Lennon’s name guaranteed maximum media attention for the Sinclair case and had turned it into a national issue. Rarely, if ever, had a protest song appeared to achieve change at such dramatic speed. After his release, Sinclair placed a call to Lennon in New York, personally thanking him for his contribution.  Leni and John Sinclair at his release

Leni and John Sinclair at his release

John Sinclair was born October 2, 1941 in Flint, Michigan and grew up in nearby Davison where discovered rhythm & blues radio while in grade school. Disc jockeys like “Frantic Ernie D” on WBBC in Flint possessed the gift of being able to consistently speak in rhyme while on-air and this had a powerful effect on Sinclair. After he graduated from high school in 1959, Sinclair attended Albion College (1959-61) and the University of Michigan, Flint College (1962-64) where he received an A.B. degree in American literature. In April 1964, he entered graduate school at Wayne State University. Sinclair completed course work for an M.A. in American literature before dropping out in 1965 to further pursue his activities in the Detroit jazz and poetry community.

On November 1, 1964, shortly after his first arrest for “sales and possession of marijuana”, Sinclair helped found the Detroit Artists’ Workshop. During the years 1964-1967, under the auspices of both the Workshop and its campus counterpart, the Wayne State Artists’ Society, Sinclair produced countless jazz concerts and poetry readings featuring Detroit talent. He was also one of the founders of the Artists’ Workshop Press which published a series of books, magazines, and free sheets by Detroit poets and writers, including several of his own works.

Sinclair served as music editor and columnist for Detroit’s Fifth Estate newspaper, one of the original five members of the Underground Press Syndicate. He worked as the local correspondent for both Downbeat and Jazz magazines out of New York, and his writings and poetry were featured in a number of other publications as well.

A second marijuana arrest resulted in Sinclair being sentenced in February 1966 to six months in the Detroit House of Correction. He first met the MC5 when they were hired to play at his jail release party during the summer. Sinclair liked the band’s innovative approach to rock and roll and allowed them to use a building at the Detroit Artists’ Workshop as a rehearsal space.

When school teacher, and fledgling rock impresario, Russ Gibb asked Sinclair if he knew of a good band with an original sound to play at the new music emporium he was opening at the Grande Ballroom in Detroit, John recommended the MC5. Gibb then offered them the position as the Grande’s house band.

In February 1967, Sinclair, his wife Leni, and Gary Grimshaw established Trans-Love Energies Unlimited in Detroit. It was described as a “total cooperative tribal living and working commune”; and Trans-Love produced dance concerts, rock and roll light shows, posters, pamphlets, books, and the Warren-Forest Sun newspaper. They also served as a cooperative booking agency for local rock groups including the MC5, the Stooges, the Up, and Billy C. and the Sunshine.

After taking over as the manager of the MC5, Sinclair helped get the band’s second single, “Looking At You”/Borderline”, released on Jeep Holland’s Ann Arbor-based A-Square label. The band’s regular gig at the Grande, which now involved opening for national acts like Cream and The Who, helped elevate the MC5’s popularity in Detroit to a much larger scale. The band was also fast becoming a lightning rod in confrontations between police and the emerging youth culture at music events in the Metro Detroit area.

Following the Detroit race riots and continued police harassment of the commune, Sinclair re-established the Trans-Love operation in two large houses on Hill Street near the University of Michigan campus in Ann Arbor during the spring of 1968. By this time, Sinclair had been busted for a third time for passing two marijuana joints to an undercover policewoman, and according to Michigan law, was facing a lengthy prison term.

In the summer of 1968, Sinclair booked the MC5 for the music festival at Lincoln Park in Chicago that was scheduled to coincide with the Democratic National Convention. When the band arrived, they found that everyone else on the bill had bowed out due to the bad publicity and negative vibes surrounding the convention. The MC5 only played a few songs before agitators planted in the crowd started a disturbance, and the Chicago police marched in and started clubbing those in attendance. The band quickly packed their equipment and fled the resulting chaos as quickly as they could.

Sinclair was instrumental in using the publicity from the event to get the MC5 signed to Elektra Records in the fall, and their first album was recorded live at the Grande Ballroom. Remote recording equipment was flown in to Detroit, and the band recorded their October 30th and 31st shows for what would become the controversial “Kick Out The Jams” album.

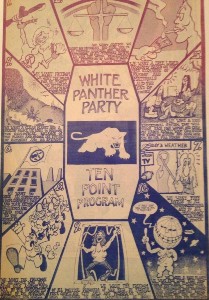

On the day after the recordings, Sinclair announced the formation of a new political division of Trans-Love Energies called the White Panther Party. Deeply influenced by Black Panther leaders Huey Newton and Eldridge Cleaver, Sinclair and Pun Plamondon formed the White Panthers and put forth its ten-point program that demanded economic and cultural freedom.  Original 10 Point poster

Original 10 Point poster

Originally conceived as an arm of the Youth International Party and organized around local issues in Ann Arbor like free concerts in the parks, the White Panther Party soon had affiliated chapters nationwide. Advocating “everything be free for everybody” and “total assault on the culture” by any means necessary including “rock and roll and dope and fucking in the streets”, the new party’s revolutionary message would be carried to the masses through the music of the MC5.

Elektra released the new MC5 album with the infamous “Kick out the jams, motherfuckers!” intro included. It caused a firestorm of controversy since it was the first major label release to contain the expletive and the first to have the word “fuck” in the liner notes, which were written by John Sinclair. In order to get played on Top 40 radio stations, the single version of “Kick Out The Jams” was recorded with the words “brothers and sisters” substituted for the offensive term.

The LP was a hit, reaching # 30 on Billboard’s Top Albums chart in 1969, despite the fact that some record store clerks had been arrested for selling an “obscene” recording. In Detroit, Hudson’s department stores refused to stock the album. Sinclair and the MC5 retaliated with an ad in an underground Ann Arbor paper that included the words “Fuck Hudson’s”. They also included the Elektra logo in the ad without first obtaining the permission of the label. This was the first in a series of disagreements that resulted in the MC5 being dropped from Elektra.  "Kick Out The Jams" LP

"Kick Out The Jams" LP

In July 1969, John Sinclair was sentenced by Detroit Recorder’s Court Judge Robert J. Columbo to 9½ to 10 years in prison. The two marijuana cigarettes he was convicted of passing in 1967 was his third offense, resulting in the harsh sentence. Sinclair’s sentencing had been delayed for two and a half years because his attorneys (Sheldon Otis and Justin Ravitz) had fought the constitutionality of Michigan’s marijuana statutes.

While behind bars, Sinclair wrote the books Guitar Army: Street Writings/Prison Writings, a collection of his writings for the underground press and Music & Politics, co-written with Robert Levin, and he continued to help direct the White Panther Party which had evolved into the Rainbow People’s Party in April 1971.

The MC5 had let Sinclair go as their manager shortly before his sentencing on the advice of representatives of Atlantic Records. The band would go on to record two solid rock and roll albums for the company, but both sold poorly and the band was subsequently dropped. By late 1971, the MC5 was without a record label and falling apart. After a new record deal fell through, the combination of career frustrations, drugs, and money difficulties caused the end of the MC5. As a result, the band most closely associated with John Sinclair was conspicuous in its absence from the event that would help gain his release from prison.

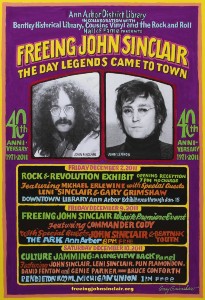

Four decades later on December 9, 2011, the Ann Arbor District Library sponsored a free concert at The Ark in downtown Ann Arbor to mark the 40th anniversary of the 1971 Free John Sinclair Rally held at the Crisler Arena. The show featured the Commander Cody Band along with an opening set by John Sinclair and the Blues Scholars.

Since Lynn-J and I had attended the original concert, we thought it might be interesting to attend the reunion. When I called The Ark about getting tickets, I was told that the event was being run by the Ann Arbor District Library, and that they were in charge of the tickets which would be given out at The Ark’s box office at 6:00 p.m. on a first-come, first-served basis. I was also advised that there was a lot of interest in the event, and that I should be there early if I wanted tickets.  40th Anniversary poster

40th Anniversary poster

At this point in our lives, the thought of driving a couple hundred miles to and from a show in bad weather and then standing in line for tickets is pretty unappealing. But when the weather forecast for the night of the show was clear and relatively mild, we were off to Ann Arbor. We love The Ark as a music venue. It’s small (350 seats), with great sound, and most always with respectful audiences who are there to listen. Both of us are completely turned off by the larger venues in Michigan where the drinking is often out of control and rude people are talking throughout the shows to each other, or on their cell phones.

We arrived in the early afternoon so that we had time to enjoy dinner at Palio’s, one of our favorite Ann Arbor restaurants, before walking across the street to The Ark to get tickets. We were in line promptly at 6:00 p.m. but there were only 7 people in line ahead of us. It took about 15 minutes for the library representative to get outside and hand out the rubber wristbands that were being used in place of tickets. The bands had a tie-dyed color scheme and freeingjohnsinclair.org printed on each. This is the library’s web site address for their collection of materials that highlight Sinclair’s activities in Ann Arbor and Detroit in the 60’s and 70’s. In addition, the Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan has a large archive of John and Leni Sinclair’s papers from 1957 – 1999.

The show itself was fun. John Sinclair opened and performed spoken word poetry over the jazz, blues, and rock backing of the Blues Scholars, a collection of highly regarded musicians from the Detroit area. Sinclair delivered his poems in the style of the beat poets of the 50’s. Wayne Kramer, former guitarist of the MC5, flew in from California as a surprise to Sinclair and sat in on most of the set.

The Commander Cody Band is now a quartet. The Commander is the only remaining member of the band that played at the rally back in 1971, and although he looks a little worse for wear, he still sounds great bashing out that country-based boogie-woogie rock and roll on his 70’s hits; “Hot Rod Lincoln”, “Beat Me Daddy Eight To The Bar”, and “Don’t Let Go”.

Pun Plamondon, Sinclair’s old revolutionary cohort, was also on hand as a master of ceremonies. Both he and Sinclair spoke briefly about what the movement had achieved all those years ago but I wondered if there was any observable evidence in Ann Arbor, which is much more conservative now than in the late 60’s when it was a center of youthful dissent.

I was surprised that the venue wasn’t filled for the free show. There were probably 300 in the audience – a far cry from the 15,000 who filled Crisler at $3 a head. Ann Arbor is a city with a population of roughly 114,000. Are the people today so apathetic and/or disinterested that they can’t even be bothered to attend something of historical significance that is free? In his introduction for his song “John Sinclair” at the 1971 rally Lennon said this: “We came here not only to help John and to spotlight what’s going on, but also to show and say to all of you that apathy isn’t it, and that we can do something. Okay, so flower power didn’t work. So what? We start again”. Lennon’s words have retained their power, especially in light of recent events in Michigan.

Although Ann Arbor is more yuppie than hippie in 2011, there apparently still are a few remnants of the counterculture around today. One is the “Hash Bash”. The first celebration of cannabis was observed on April 1, 1972 on the University of Michigan Diag, and the “Hash Bash” continues to be a popular event in the town 40 years later.

The celebration was brought about through the efforts of John Sinclair, whose political organization got behind two candidates from the Human Rights Party who were then elected to the Ann Arbor City Council. They quickly spearheaded an effort to reduce the city’s penalty for small amounts of marijuana to a $5 civil infraction, thereby essentially decriminalizing weed in Ann Arbor. Over the years the fine has been increased to a $25 ticket for a first offense. Getting involved and voting makes a difference.

As a longtime advocate of marijuana use, it probably goes without saying that Sinclair was pleased that the Michigan Medical Marijuana Initiative was passed in 2008 by a fairly wide margin; 63% of the voters in favor, while 37% were opposed. But just three years later, the common sense law is under attack by Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette.

Schuette’s victory in the 2010 general election is an excellent example of the effect of apathy on the part of Michigan voters. Although on the surface it seemed that Schuette defeated his Democratic opponent, David Leyton, rather convincingly by a margin of 52% to 43% in the election, it’s revealing to know that only 45 % of the registered voters in Michigan bothered to cast their votes in 2010. To break it down, Schuette’s victory total really represented just 22% of the registered voters in the state. Furthermore, the total number of Michigan citizens who cast their votes for the Medical Marijuana Initiative in 2008 was almost twice the number who voted for the Attorney General who is trying to overthrow the law.

The same thing happened in the 2010 gubernatorial election. Republican Rick Snyder appeared to have scored an overwhelming victory over his Democratic challenger, Virg Bernero, by a 58% to 40% margin. But with only 45% of the registered voters in Michigan casting ballots in the election, Snyder’s total represents just 26% of the voters in the state, hardly a mandate for “reinventing Michigan”.

Perhaps the results in both of the above races would have been the same even if over 90% of the registered voters had cast their ballots. I could accept that, but not 45%. To quote Jessica Reiser, president of the League of Women Voters of Michigan; “To make democracy work, we have to have citizens involved. And voting is the best way to do that”. To become involved, people need to take the time to learn about the issues and then do their civic duty and cast their vote. The stakes are high. A government in which decisions are made by a minority of its citizens is a democracy in name only.

In what will probably be the perfect storm of negative advertising accompanying the upcoming presidential election, it will be easy to sit back and do nothing, to rationalize that your vote doesn’t really mean anything. Why bother? I’m too busy. I don’t want to stand in line. They’re all the same. It won’t make any difference if I vote or not. The lyrics of John Lennon’s "Working Class Hero", issued on his first solo album, “John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band”, address apathy. Although Lennon is no longer with us, his words from over forty years ago still ring true.

Keep you doped with religion, sex, and T.V.

And you think you’re so clever and classless and free

But you're still fucking peasants as far as I can see

A working class hero is something to be...

- John Lennon