The story of Flint DJ Peter C. Cavanaugh and one of Michigan's fascinating music venues, located in the small town of Davison, Michigan.

“We are all outlaws in the eyes of America” – Jefferson Airplane

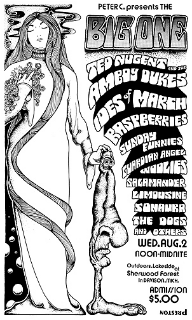

Although the repercussions from the 1970 Goose Lake International Music Festival in Jackson County had effectively ended the rock festival era in most parts of Michigan, the events did continue until 1974 in what would seem to have been the most unlikely of locations. Sherwood Forest was located in Richfield Township, just east of Flint and north of the small town of Davison. The amusement park was the brainchild of Don Sherwood, a farmer turned businessman; and the music festivals held there were organized and promoted by an enterprising disc jockey named Peter C. Cavanaugh.

The open drug use and traffic snarls at Goose Lake had made the festival something of a political football kicked between Michigan’s Governor William Milliken, State Attorney General Frank Kelley, the Michigan State Police, the Jackson County Sheriff Department, as well as the Jackson County prosecutor. The political blowback caused the cancellation of a planned Labor Day festival at the site featuring Jefferson Airplane, Fleetwood Mac, and Detroit’s Savage Grace. Goose Lake Park had been advertised as “The World’s First Permanent Festival Site”, but the three-day event in August would prove to be the only one ever held there.

Perhaps things would have went much more smoothly at Goose Lake if owner Richard Songer had taken a few pages from the playbook used by Don Sherwood and Peter C. Cavanaugh at Sherwood Forest. The pair had been running very successful day-long festivals at the amusement park since 1969.

During the 1950s, Sherwood had purchased several pieces of property adjacent to his farm. Over a period of several years, he chopped down trees, leveled off fields, excavated a small lake, put in a baseball diamond, horseback riding trails, and a number of miniature rides and games. In 1958, he built a 75-foot-by 80-foot hall which hosted dances, weddings, political rallies and other events.

By the time the 1960 census was taken, an outdoor stage had been constructed at Sherwood Forest and the population of Davison, a prosperous middle-class and predominately white suburb of Flint, had more than doubled to 3,761. Rock and roll made its first major impact at the amusement park in 1964 with an appearance by two of Motown’s biggest acts: The Miracles featuring Smokey Robinson and Stevie Wonder.

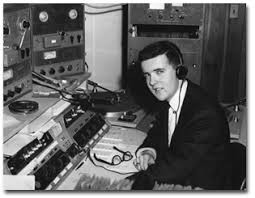

That same year, Sherwood Forest hosted its first “battle of the bands” which saw The Jazz Masters with drummer Donnie Brewer compete against The Derelicts which featured Mark Farner on guitar and vocals. The Jazz Masters won that battle; and the next year they would go on to join Terry Knight, change their name to The Pack and recruit Farner as their bass player.  Peter C. Cavanaugh

Peter C. Cavanaugh

Peter C, Cavanaugh joined WTAC, Flint’s highest-rated AM radio station, in 1963. He left his radio job at WNDR in Syracuse to come to Flint at the invitation of his hometown friend, and WTAC’s most popular disc jockey, Bob Dell. Cavanaugh made an immediate splash at WTAC by managing to come up with the only radio station interviews of The Beatles during their first Michigan appearance in September at the Olympia Stadium in Detroit.

After returning to Flint, Cavanaugh combined the interviews with recordings he made of The Beatles’ 25-minute performance into an hour-long program titled WTAC Meets The Beatles that was a ratings smash for the station. Shortly thereafter, Cavanaugh was appointed the program director at station KSO in Des Moines, Iowa. He left after the station moved away from its rock and roll format and took a disc jockey position at WTLB in Utica, New York. Cavanaugh returned to WTAC in late 1966.

By this time, rock and roll had begun its transition to ‘rock’ led by the innovative recordings of The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, and The Byrds to name just a few. A number of new Michigan bands had also started to have some major impact on the Billboard charts; most notably Mitch Ryder and The Detroit Wheels, ? and The Mysterians, and Tommy James & The Shondells. Terry Knight & The Pack, The Rationals, The Woolies, and Bob Seger & The Last Heard also had minor hits on the national charts.

In the spring of 1966, Bob Dell had begun to present music concerts at Mt Holly, a popular ski area just south of Flint on the Dixie Highway. Mt. Holly had a large lodge which was basically unused during the non-skiing season and Dell was able to rent the facility for $100 a night and split the profits from the food and drink concessions with the lodge owner. Mt. Holly quickly became one of the hottest music venues in the state in large part because WTAC provided free broadcast announcements for all disc jockey related functions; and the fact that the venue was located just 10 minutes south of Flint, 35 minutes northeast from Ann Arbor, and 50 minutes north of Detroit.

Mt. Holly continued to be a goldmine for Dell through the summer of 1967. In the fall, he and Cavanaugh came up with the innovative idea of using the last two hours of Cavanaugh’s nightly show on Mondays through Friday to feature only the “heavy” rock music rather than the station’s normal Top 40 mix. The WTAC Underground did away with the station’s regular jingles and presented artists like Iron Butterfly, Steppenwolf, The Grateful Dead, and the Jimi Hendrix Experience as well as Michigan bands including The Amboy Dukes, The Scot Richard Case, The Unrelated Segments, and The Frost, all of whom regularly appeared at Mt Holly.

WTAC Underground enabled Cavanaugh to become well acquainted with area bands. This came in very handy when in April of 1969 WTAC assumed sponsorship of an outdoor event to be called Wild Wednesday at Sherwood Forest. Don Sherwood was looking to get publicity for his park, and WTAC’s idea was to sell sponsorships to area businesses that would display their products or sell their goods at Sherwood Forest with the amusement park open for free rides. Sherwood would make money off the crowds from his food concessions, swimming facilities, and games of chance.  Peter C. Cavanaugh and Johnny Parker

Peter C. Cavanaugh and Johnny Parker

Cavanaugh and his partner, fellow WTAC announcer Johnny Parker (a.k.a. Johnny Irons), saw an opportunity to add a rock concert to the proceedings in the fenced-in patio area between the park’s lake and its unfinished new hall. The June 21st event was heavily promoted on WTAC and drew a crowd of over 10,000 people. In addition, 4,000 music fans paid $2 each to attend the 8:00 PM until midnight concert that Cavanaugh and Parker promoted, featuring six Michigan bands headlined by The Bob Seger System and The Rationals.

The success of the first Wild Wednesday event led Cavanaugh and Parker to promote regular concerts at the Center Building in Lapeer, the Owosso Armory, the Big Wheel roller rink in Bay City, and the County Fairgrounds in Midland. The duo’s next event at Sherwood Forest was a Grand Opening Concert at the park’s brand new hall that was scheduled for the third Sunday in October in 1969. Cavanaugh felt he had the perfect headliner for the big event – the MC5!

Cavanaugh had seen the MC5 play at Delta College and worked with them for the first time at the Foxy Lady (formerly called Band Canyon) in Bay City and was impressed by the band’s power on stage. The MC5 was also the most controversial band in Michigan and probably the entire United States in 1969. The title song of their debut album, which had been recorded live at the Grande Ballroom in Detroit, had been released earlier in the year with the infamous “Kick out the jams, motherfuckers!” included. It marked the first time that the F-word had appeared on record issued by a major label. The liner notes, written by band manager John Sinclair, also included the dreaded F-word, and the combination of the two reportedly caused some record store clerks to be arrested for selling an “obscene” album.

The band and their manager had further outraged many older Michigan residents and their own record label when they responded to the refusal of the Hudson’s department stores in the Detroit area to stock their album by placing an ad in an underground Ann Arbor newspaper with the statement “Fuck Hudson’s!”, accompanied by the unauthorized use of the Elektra record company logo.

John Sinclair was born in Davison, nicknamed “The City of Flags”, on October 2, 1941. He was the son of a career employee at Flint’s Buick Assembly Plant and had graduated from high school in 1959, shortly after Don Sherwood had opened his amusement park. He went on to earn a B.A. degree in American literature at the University of Michigan, Flint College, and then earned a M.A. at Wayne State University. He began managing the MC5 in 1966 after they had played at a welcome back party for Sinclair after serving a six-month sentence in the Detroit House of Correction for his second conviction for possession of marijuana.

In 1968, Sinclair had helped form the White Panthers, a far left, anti-racist political organization. It was started in response to an interview with Huey Newton, co-founder of the Black Panther Party, in which he was asked what white people could do to support the Black Panthers. In November, the White Panthers released a ten-point statement that fully supported and endorsed the Black Panthers, a group the F.B.I chief J. Edgar Hoover had labeled “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country”.

Among other things, the White Panther’s manifesto called for free food, clothing, housing, medical care, the end of conscripted armies, and the freeing of all prisoners; but the point that got the most publicity and riled up mainstream Michiganders was their call for the “Total assault of the culture by any means necessary including rock and roll, dope, and fucking in the street”. Although the MC5 cared much more about being regarded as a great rock and roll band than far-left revolutionaries, they went along with the program and were put forth as the musical face of the White Panthers.

Like most Michigan residents, Davison authorities were aware of the gun violence that had been taking place between Black Panther members and police officers in both Los Angeles and Chicago during the past year and were not pleased that a native son, who was a leader of the White Panthers and had referred to the police as “pig/jerk-off/asshole/prick-cops” in “blue Nazi uniforms”, was bringing his obscenity-spewing rock band to their town.

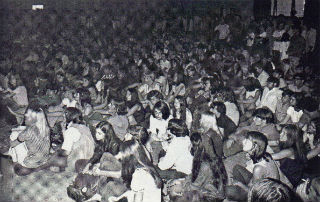

Davison City and Township Police Departments were under the command of Chief of Police Ralph Rogers. After listening to the MC5’s “Kick Out The Jams” LP and having discussions with the County Prosecutor’s Office, Rogers devised a plan to bust the band and its manager if any obscenities were used during the concert.  Crowd in the Sherwood Forest Lodge

Crowd in the Sherwood Forest Lodge

WTAC promoted the MC5 appearance at Sherwood Forest as The End of the World concert. The station produced a heavily rotated 60-second announcement that included brief samples of the band’s music. Posters and flyers were also printed and circulated in area record stores, malls, and theater complexes. The event was scheduled to run from 6 until 10:00 p.m. and tickets were priced at $3. Don Sherwood would receive 50% of the profits after all expenses were deducted, and would also contribute the same percentage in the event of a loss. Cavanaugh and Parker would evenly divided or pay the rest. Sherwood would also make all the money from his food and drink concessions at the lodge.

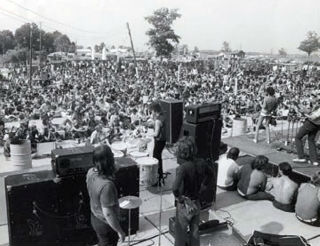

Since the MC5 were the hottest ticket in Michigan, the chances that the concert would lose money were slim. By show time, 2,000 rock and rollers had crammed into the new Sherwood Forest lodge and several hundred had to be turned away at the door. By the time that the MC5 had taken the stage, Chief Rogers had assembled a force of over four dozen officers from Davison and surrounding townships outside of the lodge. Near the end of the band’s set, and after lead singer Rob Tyner launched their biggest hit with “Kick out the jams, motherfuckers”, the signal was given for the police to move into the lodge and arrest the MC5 on obscenity charges.  Wild Wednesday audience 1970

Wild Wednesday audience 1970

As the band finished “Kick Out The Jams”, they noticed the police entering the front doors, thanked the crowd, and slipped out the back door, got into their van and quickly drove back to Ann Arbor. According to Cavanaugh’s highly entertaining book, Local DJ, it took the police about five minutes to get through the packed crowd, many of whom apparently thought the raid was part of the show. When Chief Rogers finally got to the stage, there was no band to arrest and he proceeded to get into a shouting match with both Cavanaugh and Parker.

Don Sherwood was upset by the incident and its coverage in the Flint Journal and on the Flint area television stations. His relationship with WTAC had been very profitable, but he was understandably concerned with the reputation of Sherwood Forest and the importance of staying on the good side of local law enforcement. With the very real possibility that the MC5’s End of the World concert might be the end of his lucrative arrangement with Sherwood Forest, Cavanaugh came up with a simple and effective plan.

After seeking legal counsel, he discovered that he probably would not be successful in confronting the police with charges of illegal entry, searches, and threats. Instead, Cavanaugh went in the opposite direction and sent a Western Union message to Chef Rogers and the Davison Police Department thanking them for their efforts at the MC5 concert and asked them to take official charge of security at all forthcoming concerts at Sherwood Forest. In addition, both Rogers and the off-duty officers that he assigned would be reimbursed for their efforts by the promoters so that no City or Township tax dollars would be used.  Ted Nugent and The Amboy Dukes at Sherwood Forest

Ted Nugent and The Amboy Dukes at Sherwood Forest

Cavanaugh addressed the issue of obscenity by proposing that all future groups contracted for performance at Sherwood Forest would be asked to avoid specific language as a condition of appearance. The contract would state that the word “fuck” or any form of “fuck” could not be used during performance. Any “fuck” uttered would result in forfeiture of payment to the artist.

The beauty of Cavanaugh’s plan was that although it seemed like a major victory for Chief Rogers, it specified that the sole purpose of the security presence was to assure peaceful assembly and guard against obscenities from the stage. It was emphasized that the police were being paid by the promoters to protect the crowd in every way possible. This all but guaranteed that the Sherwood Forest audiences would have the freedom to get high and peacefully enjoy the music without fear of being hassled by the cops.

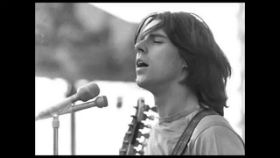

The new arrangement worked well at the regular Sunday night concerts at Sherwood Forest but the big test would come at the 1970 Wild Wednesday festival scheduled for June 24th. With 12 groups in 12 hours, from noon until midnight, with twin concert stages and no recorded music, this was going to be a much bigger production than the previous years. The line-up included the Bob Seger System, Amboy Dukes, MC5, Rationals, Brownsville Station, Alice Cooper, Frijid Pink, and Teegarden and Van Winkle.  Bob Seger at Sherwood Forest 1969

Bob Seger at Sherwood Forest 1969

To accommodate the larger crowd, Don Sherwood mowed acres of adjacent fields for additional parking. Security was provided by Davison’s off-duty Sheriff’s deputies, many on horseback. Cavanaugh had also recruited a large group of trusted volunteers called the “Roadies Squad” that were dressed in Sherwood Forest T-shirts and divided into five teams to help with equipment, guard dressing rooms, assist with security, and help with anything else that would help the festival be successful.

Wild Wednesday 1970 was performed between the Sherwood Forest lodge and the adjacent lake area. It was blessed with a beautiful day, a crowd of over 20,000, and was a complete success. Six weeks later, the massive Goose Lake International Music Festival crashed and burned after it was beset with traffic snarls, poor security, run-ins with state and local authorities, and negative press.

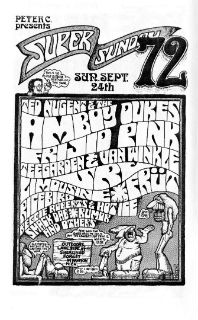

While rock festivals were declining around the state in the wake of Goose Lake, the Wild Wednesday events at Sherwood Forest were going strong. Taking advantage of its close location to major Michigan cities, (less than an hour’s drive from both Detroit and Ann Arbor to the south, Saginaw from the north, and Lansing from the west), Sherwood Forest scheduled two day-long outdoor festivals for the summer of 1971.

The first, on June 23rd, featured the first acoustic performance by Bob Seger. The Bob Seger System had broken up, and Seger’s latest album, “Brand New Morning”, was a departure from his earlier hard-rocking albums and singles. According to Cavanaugh’s book, Seger’s acoustic set didn’t go over well with the crowd of 12,000, but things picked up considerably after Teegarden and Van Winkle joined him on stage and they turned up the volume.

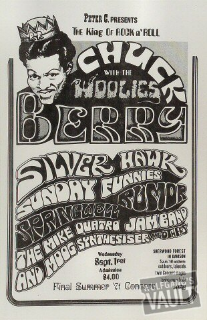

The final summer festival of ’71 was held on September 1st and was headlined by rock and roll legend Chuck Berry. Berry toured without a band and often recruited local musicians wherever he appeared. This could be a hit or miss proposition; but whenever he played in Michigan or in the other Midwestern states, he requested The Woolies as his backing band. The Lansing group had reached the Billboard Hot 100 in 1966 with their cover of Bo Diddley’s “Who Do You Love”. The Woolies’ first album, “Basic Rock”, was released in 1970; and it included photos of the band on stage with Chuck Berry during a performance at the Eastown Theater in Detroit that same year.  Chuck Berry with The Woolies

Chuck Berry with The Woolies

Berry had just recorded his new album, “San Francisco Blues”, at the studio that The Woolies had constructed in Lansing. Besides Berry and The Woolies, the Wild Wednesday line-up also included Michigan bands: Silver Hawk, The Sunday Funnies, Springwell, and the Mike Quatro Jam Band.

The 1972 summer season at Sherwood Forest started off with a bang with another noon until midnight festival featuring Ted Nugent and the Amboy Dukes, Bo Diddley, Mitch Ryder and Detroit, April Wine, The Whiz Kids, Julia, Ormandy, Bob Seger with Teegarden and Van Winkle, and a special appearance by Mickey Dolenz of The Monkees. 14,000 music fans filled the park and marijuana smoke filled the air.

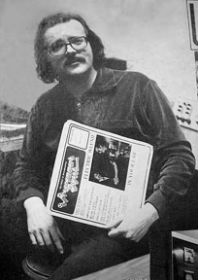

Peter C. Cavanaugh 1970s

Peter C. Cavanaugh 1970s

Things had already begun to change, however. The rock and roll business was becoming increasingly more corporate. Cavanaugh explained in Local DJ that band prices were starting to soar as major booking agencies were grabbing up the bigger acts and demanding much higher guarantees and percentages. In earlier years, almost every city had one or two promoters who would bring in major headliners and use talent from the area to open each show.

The exposure afforded the opening acts made it possible to use the same local groups to draw 500 or 600 to smaller halls, teen clubs, amusement parks, and smaller auditoriums. When the larger agencies began signing acts and calling the shots, the game changed. A requirement in obtaining a major band was to use other artists represented by the same agencies as opening acts on the same bill. Local promoters and local acts began to get squeezed out. The new way of doing business disrupted the natural progression of rock and roll bands and ended up negatively affecting the local music scene in Michigan.

On January 1, 1972, the legal drinking age was reduced from 21 to 18 all across the state and as a generation aged and became legal, the only venues for local and regional acts became taverns and bars. Methaqualone, sold under the name Quaalude in the U.S.A., was also becoming an increasingly popular recreational drug in Michigan. As the popularity of alcohol and ‘ludes’ and other downers increased, the audiences at the Wild Wednesday festivals changed as well.

The first Wild Wednesday of 1973 was scheduled for June 20th. It was headlined by Britain’s Climax Blues Band, Sugarloaf, Frijid Pink, and Mitch Ryder.

The second Wild Wednesday was held just three weeks later with headliners Blue Oyster Cult and REO Speedwagon. When REO had to back out due to a recording deadline, their booking agency substituted Joe Walsh, who had left the James Gang in 1971 and formed a new band called Barnstorm. He had just completed his second solo album with his new band called “The Smoker You Drink, The Player You Get”. Walsh performed a blistering 15-minute version of his soon-to-be hit single “Rocky Mountain Way” for the first time before a live audience at Sherwood Forest.

The final Wild Wednesday was held the following summer on June 25, 1974. Montrose, with lead singer Sammy Hagar, along with Spooky Tooth and Bob Seger headlined the festival. Tickets were $5.00 and 10,000 attended the event.

Besides the corporate shift in music promotion, Cavanaugh was also unhappy with the evolution of the drug scene at the Sherwood Forest concerts. He wrote that 1973 was “the year of the Quaalude” and that audiences now seemed to want to get out of it and away from it all as opposed to getting high and attempting to enjoy the music from a heightened, expanded perspective. Putting on a festival in which large segments of the audience were in a downer-induced stupor just wasn’t as much fun.

The incident that indirectly led to the end of Wild Wednesdays, however, was a tragic accident. An ambulance that had been racing toward Sherwood Forest went out of control at a high rate of speed, killing both the driver and his assistant. An unidentified caller had reported a drug emergency at the site. Although the drug emergency was never verified and the media did not directly blame the festival, the two deaths provided a rallying point for those neighbors and local government officials who had been consistently opposed to the concerts at the amusement park over the years. Tired of the mounting pressures and feeling that the rock and roll business had probably outgrown Sherwood Forest, Cavanaugh and Sherwood voluntarily decided to bring the events to a close after five very good years.  Sherwood Forest Lodge before the fire

Sherwood Forest Lodge before the fire

In 1980, Don Sherwood sold his property in Richfield Township, which included Sherwood Forest. In 1989, the Sherwood Forest lodge was completely destroyed by fire and the site was abandoned for a number of years. Like almost all of the venues that played host to so much of Michigan’s great music from the vinyl era, there is no historical marker at the former home of Sherwood Forest. Its importance resides solely in the memories of those who were there.

Sources:

Local DJ – A Rock ‘N’ Roll History by Peter C. Cavanaugh, 2001. Most of the above was taken from Cavanaugh’s entertaining and informative memoir of his life and career. The book is now available in a kindle edition. Highly recommended.

Grit, Noise And Revolution – The Birth Of Detroit Rock ‘N’ Roll by David A. Carson, 2005. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor.

6/99 Sherwood by Justin Rogers. Mlive.com February 28, 2008.