The controversy surrounding Bay City's very first first teen club and the secret that led to its closing.

As rock and roll moves through its sixth decade, it’s easy to forget that in the 1950s it was characterized by government, religious, educational, and media spokespersons as immoral and sinful – and its purveyors as lazy and shiftless juvenile delinquents.

In an era of conformity dominated by conservative politics and the banal and bland music of the Hit Parade and Mitch Miller, some even believed that rock and roll was all part of the world communist conspiracy to destroy the values and morality of American youth. in 1956 Frank Sinatra joined the anti-rock and roll forces when he stated, "Rock 'n' roll smells phony and false. It is sung, played, and written for the most part by cretinous goons and by means of its almost imbecilic retardation and sly, lewd in plain fact dirty lyrics....it manages to be the martial music of every side-burned delinquent on the face of the earth."

The adult antagonism toward rock and roll music also reflected the inherent racism of the era. The 1950s was a time of tense race relations in the United States, the historic Civil Rights legislation had yet to be passed, and racial tension between blacks and whites was on the rise, especially in the South. Most white parents perceived rock and roll as fundamentally black in both origin and nature, and judged it as a type of subhuman "jungle music".

Early rock and roll music was not complex – it contained elements from rhythm and blues, gospel, folk, country, Latin, blues, and pop. There were emotion-laden vocals. The lyrics told teen tales about romance, dancing, school, music, and sometimes veiled references to sex – just simple, mostly innocent stories about everyday life.

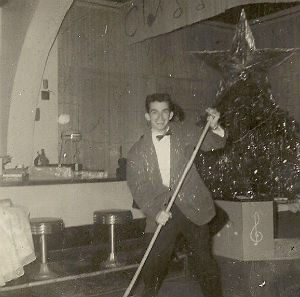

To most adults in Michigan and across the nation, however, there was something unnerving about the music. To parents, many of whom were socialized by training in the military, the hierarchy of the workplace, and the accepted roles in the home, rock and roll produced a frighteningly spontaneous and sensual reaction in their children.  Mickey Higgins at the Big Bop

Mickey Higgins at the Big Bop

Despite adult disapproval, rock and roll became a catalyst for teens to form their own group identities – a comradeship of those who felt good about, and identified with, the music. Mickey’s Big Bop was Bay City, Michigan’s first teen dance club, and it was located in a small second story hall above Midland Street on the city’s West Side. The Big Bop was the brainchild of Edward “Mickey” Higgins, who both fashioned and operated the club something along the lines of ABC TV’s popular teenage dance program, American Bandstand.

Mickey’s Big Bop opened for business on May 10, 1957, and ran successfully until August of 1959, when the club was denied a dance license by the Bay City Commission. On the surface, it appeared that the license denial, based largely on a letter written by a prominent and powerful member of the community, was a reflection of nationwide fears that rock and roll led to juvenile delinquency, immorality, and racial mixing.

Over fifty years later, however, information has been uncovered that indicates that the letter that led to the club’s closing was written because of an on-going conflict between a father and his son, and initiated by a near-tragic family event. The story of Mickey’s Big Bop turned out to be much more complex than it initially appeared. On one hand, it’s a tale involving political cronyism and the destructive power it can wield. On the other, it’s a story of a young entrepreneur, the rock and roll music played at his club, and the teens that came to dance.

Mickey Higgins was born in Ohio in 1933, and moved to Bay City with his parents. He grew up in the Banks area on the city’s West Side. Higgins married the former Patsy Lincoln in 1951. During the early 1950s, Higgins worked as a manager for Johnny’s Drive-In at 805 N. Euclid during which time their first daughter, Wendy, was born.

In late 1954 Higgins received his draft notice and was inducted into the Army. Mickey was diagnosed with diverticulosis near the end of his hitch in the military and was sent to the Valley Forge Army Hospital in Philadelphia in 1956 for treatment. While in the hospital, he had a chance to watch a locally produced television show called American Bandstand.

After his release from the hospital, Higgins attended an American Bandstand broadcast. Located in “Studio B” at 4548 Market Street in Philadelphia, there was only space for 200 teenagers amidst the show’s props, television cameras, and bleachers. Mickey had the opportunity to observe how things were run on the show, and the way host Dick Clark interacted with the teens from a raised podium as he played the latest hits. During his visit, he also saw Andy Williams make his debut appearance on the program. Higgins was probably the first Michigander to know about American Bandstand, since it would not be broadcast nationally until August of 1957, three months after the Big Bop opened.

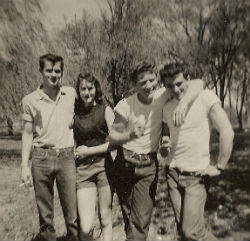

The actual idea to start a dance club of his own came after he returned to the Banks area in Bay City and listened to several neighborhood teens complain that “there was no place to go”. Higgins was working as a foreman at Saginaw Bay Industries, a small factory located at 920 N. Water Street. He also had a part-time job as a short order cook at Gardner’s All American Restaurant on Midland Street. Vivian “Ma” Gardner owned the small hall above her restaurant, and Higgins began talking to her about renting and renovating the space, with the idea of converting it into a dance club for teenagers.  Mickey Higgins (R) and friends

Mickey Higgins (R) and friends

Higgins recruited a number of his friends as a work force, and they helped with the plumbing for the restrooms on the north wall. They built booths along the south and west walls where teens could sit and socialize. The volunteers also constructed a typical 50’s sit-down counter behind which was a grill, soft drink dispensers, and racks for potato chips, popcorn, and candy. The bandstand was located along the east wall in front of the large wooden dance floor. The club’s fire escape was a set of metal stairs, located at the rear of the upstairs hall, that ran down to the alley behind the building.

Mickey also brought in a couple of bumper pool tables and pinball machines for the club and purchased a large air-conditioning unit for the facility. Several teenagers, including Patti (Woods) LaLonde, pitched in with the painting and wall decorations. Patti lived just a block away from Mickey’s parents in Banks and would often babysit for Mickey and his wife Pat when they lived on Chilson Street. Looking back fifty-four years, she remembers the Big Bop: “It was such a nice club. Everyone loved going there. It was Bay City’s American Bandstand. ”

”

Like Mickey Higgins, Jiles P. Richardson was also drafted into the U.S. Army while married with a small daughter. After his discharge, Richardson returned to his pre-Army occupation as a disc jockey in Beaumont, Texas. Higgins heard about Richardson, who had begun calling himself “The Big Bopper”, when he made the national news after breaking the record for continuous on-air broadcasting by performing for a total of five days, two hours, and eight minutes. (This event happened a year before The Big Bopper’s recording of “Chantilly Lace” made him a rock and roll star.)

Mickey was more intrigued by the Big Bopper’s moniker than his on-air record, so he decided to name his new dance club the Big Bop. It was a perfect fit. The “Bop” was a popular teen dance step in the 50s, and the term had also been used in a number of rock and roll songs in 1957; Gene Vincent’s “Dance To The Bop” and “Bluejean Bop”, and Carl Perkin’s “Boppin’ the Blues”.

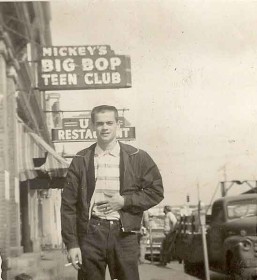

After deciding on the name, Higgins had a sign reading “Mickey’s Big Bop Teen Club” made for the building, and he used the same company to letter the name on the sides of his Ford station wagon. Mickey advertised his new club at Lucky’s Record Shop, located next door to Gardner’s Restaurant, and made a deal to get his 45s at a discount. He set up a running account with owner Frank “Lucky” Peplinski, and he often sent kids down from the Big Bop to pick up the latest sounds.  Phil Dyer on Midland St.

Phil Dyer on Midland St.

As things started to take off, Higgins formed a Big Bop membership and set up some basic rules: no one was allowed to enter if they had been drinking, and no one would be re-admitted after leaving the club. There was no fee to be a member, but there was 50 cent door charge for entry.

To prevent trouble, Higgins employed Kenny Uhl and Russ Beffrey, two off-duty police officers from Bay City, as security for the club. Mickey also used some of the older club members who were leaders, including Phil Dyer and Bill LaPage, to help keep things under control. Loitering was not allowed, and the guys would also police the back alley and the parking area behind the club because Higgins didn’t want any drinking in the cars. As payment, the leaders would be admitted at no charge and receive free soda pop, potato chips, and burgers.

Sharon (Polzin) Gage grew up on East North Union and attended St. Mary’s Catholic School. Sharon first met Mickey when the club opened and she started going to the dances. She remembers that the word spread like wildfire once the Big Bop opened. Sharon was artistic, and she made a number of posters promoting the club; but she recalls that the most effective way that the Big Bop was advertised was by word-of-mouth.

Once the club was up and running, Higgins quit his job at Saginaw Bay Industries and put all of his energy into the Big Bop. It was a family operation. Pat Higgins took admissions at the door most nights, and Mickey would play the music from the club’s bandstand. He also took care of all the food concessions at the club. “Ma” Gardner would come up periodically, but she let Mickey run things the way he wanted. Higgins remembered that she was very interested in the kids who came to the club, and Mickey described her as being “a wonderful lady.”

Entry to the Big Bop was through a stairwell located next to Gardner’s Restaurant on Midland. After just a few weeks, it was filled each night with teens waiting for the doors to open in a line that often stretched out onto the street. For most of the club’s run it was open Friday through Sunday. But when the Big Bop first started, Mickey kept it open all week as he attempted to let the club build up. The curfew on Friday and Saturday nights was 11:30 p.m., and it closed at 10:00 p.m. on other nights.  Wally Casper and Sue Willette at the Big Bop

Wally Casper and Sue Willette at the Big Bop

Dancing to rock and roll music is what drew the kids to Mickey’s Big Bop. Early group dances like The Stroll, Bunny Hop, and Mexican Hat Dance were popular at the club, and Mickey would sometimes even throw in a polka or two. But it was the latest hits of Elvis Presley, the Everly Brothers, Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, Bill Haley And His Comets, Buddy Holly, Pat Boone, Bobby Darin, Fats Domino, Duane Eddy, Ricky Nelson, and Little Richard that dominated the turntable at the Big Bop.

The doo-wop sounds of Frankie Lymon and The Teenagers, The Dell-Vikings, and The Platters also drew the teens to the dance floor, and if it was a fast song, like Danny & The Juniors’ “At The Hop”, the kids would often dance all together. Colleen (Sutter) Richter remembered that sometimes the floor was so crowded that you could barely dance without bumping into someone.

On Sunday nights, DJ Johnny Hagerman from WWBC-AM would often do a live broadcast from the Big Bop. On occasion, the club would feature live music, usually from local bands like Bobby Jones and The Blazers. But on most nights Mickey played the records, doing his best impersonation of Dick Clark.

Colleen (Sutter) Richter was born in Bay City and grew up on N. Henry Street. She first saw Mickey Higgins working outside the club when she and her friend Diane Pacynski were sitting in Munley’s City Dairy on the corner of Walnut and Midland. Looking back on those days, Colleen described Higgins as “the guy that every girl who went to the club had a crush on. He had charisma, he was good-looking, flirtatious, and he had a way with kids. Everybody liked him and they were more than happy to work for free to get the club up and running.” Colleen’s friend Sharon (Polzin) Gage agreed; “Mickey got along with everybody. He treated people like he wanted to be treated, and everyone respected him for that.”

Both Colleen and Sharon would sometimes get in free to the Big Bop if they would help clean up afterwards. The work was worth it to the girls, as they both loved rock and roll and came to the club to dance and have fun. The girls were 8th grade classmates at St. Mary’s when they started going to the Big Bop, and they soon discovered there was a price to be paid at school for the good times they were having at the club.  Sharon Polzin and Colleen Sutter

Sharon Polzin and Colleen Sutter

The nuns St. Mary’s felt that rock and roll was “the Devil’s music” and chastised the girls for going to the club. But Colleen and Sharon were also being treated like outcasts by the other kids at school who referred to them derisively as “the big boppers”. Colleen felt that a lot of the abuse came out of jealousy; and that the name-calling was a reflection of parents who would not permit their children to go to the club and some who would not even allow rock and roll music to be played in their homes.

The peer pressure was such that by the end of the school year, neither Colleen nor Sharon wanted to attend the Catholic school anymore. They both enrolled in the West Side’s public high school, T. L. Handy, for their 9th grade year.

Higgins was very aware of the negative adult attitudes toward rock and roll and his club in the community and took some steps to combat it. Sharon remembers that anytime parents wanted to visit, they were welcome. Parents got in for free, were given coffee, and could stay as long as they wanted. Sharon claims that her mother came one time and that other parents came as well.

Donna (Short) Groya grew up just off Midland Street, and although the Big Bop had its enemies, she remembers the club as “a great hangout for the kids who lived in that area.” Donna started going there in 1957 when she was 16. She said that her parents didn’t really care that she was going to the Big Bop because she had a curfew and had to be home by a certain hour.

Colleen’s situation was a little different. Her parents didn’t like her going up there. Her father, like some other dads, did not like Mickey. Mr. Sutter described him as “shady”. Colleen’s father was a truck driver, however, and was gone most of the time. Mrs. Sutter was a stay-at-home mother who did not want to argue after a hard day of keeping house. Colleen says she would ask her mother to come up and visit the Big Bop, but she would say “you’re just going to behave yourself if I go up there.”

In a recent interview Colleen remembered that “most of the kids who went to the club came from broken or dysfunctional families. Many had been in trouble, but the club kept them from getting in more. The boys tried to look like Elvis by adopting the “hood look” with slicked-back hair that fell over their foreheads.” The clientele at the Big Bop was overwhelmingly white, but Colleen estimates that about 10% of the regulars were Hispanic. This fact undoubtedly raised the eyebrows among the segment of adults opposed not only to the club’s existence, but any form of racial mixing as well.  Colleen Sutter and Phil Dyer at the Big Bop

Colleen Sutter and Phil Dyer at the Big Bop

Elvis Presley’s hip-shaking singing style had made him the early poster boy for the anti-rock and roll forces. Prior to his induction into the Army, Elvis was shown only from the waist up during his last appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show. Sullivan did this in order to placate older viewers offended by past Presley performances on television.

In May of 1958, however, 22-year-old Jerry Lee Lewis ignited the first big rock and roll scandal during a tour of Great Britain when it was discovered that his third wife was his 13-year-old second cousin. The news caused an uproar that resulted in the cancellation of his tour, and the negative publicity followed him to America where he was condemned by churches and blacklisted from the radio, effectively bringing his career to a screeching halt.

The Lewis scandal may have inadvertently affected the Big Bop inasmuch as several of Mickey’s older friends liked to hang out with him at the club. This fact led to rumors being circulated about inappropriate contacts among the older guys and the younger girls at the club. One older club member, Jack Kuhn, was not part of those rumors, but he would become one of the central figures in the eventual closing of Mickey’s Big Bop.  Ray Kuhn

Ray Kuhn

Jack Kuhn came from a well-to-do Bay City Family. He was the son of Ray Kuhn, the news editor of The Bay City Times. Ray was very active in politics. Besides his work at the Times, he had regularly written anonymous columns for another of the city’s newspapers, The Bay City Democrat. Ray had done well enough in his profession that he had bought a summer cottage for his wife and children on Brissette Beach in Linwood, and he had high expectations for his first-born son Jack.

The Saginaw River divides Bay City into the East Side and the West Side. Jack Kuhn was an East Side kid. The Kuhn family belonged to St. James Parish and lived in a comfortable two-story home at 317 Fitzhugh Street, just four city blocks from St. James Catholic School where Jack, his sister Pat, and younger brother Mike all attended classes.

Jack suffered from epilepsy. Most people during the 1950s had little knowledge of the neurological disorder, and the affliction marked him at the school as someone different, or even a little weird, during a time when conformity was the order of the day. The seizures that he experienced were not only distressing to Jack, but also a jaw-dropping experience for his classmates to witness.

During his sophomore year at St. James, Jack suffered a serious head injury during a football game. According to a former teammate, Jack had suffered seizures in the locker room before the injury, but the episodes seemed to worsen after the blow to his head. It was because of this situation that Jack dropped out of school after turning sixteen.

Mike Kuhn, who was 10 years younger than Jack, describes his father as an “extremely strict parent who had a great belief in knowing what is right and what is wrong”. Ray Kuhn was also a very influential person in Bay City and could often be found holding court in the bar of the Imperial Hotel, located just down the street from the Bay City Times, along with other members of the newspaper’s editorial staff and the political elite of the city.

Jack started rebelling against his father as a teenager by using alcohol. Although Ray Kuhn rarely drank whiskey at home, he had it on hand for guests and political friends who stopped by. Jack’s first drinks came from exchanging colored water for whiskey in his father’s well-stocked liquor cabinet. From that point on, Jack began drinking heavily, hanging out with some dubious new friends, and getting into trouble. These incidents occurred well before Mickey’s Big Bop opened for business.

Ray loved his son and was concerned about his future, but Jack’s misbehavior and the resulting problems it created were also an embarrassment to him, especially because of his standing in the community. His solution was to put Jack to work and have him learn something about responsibility by running a small business. Ray built a popcorn stand for Jack to operate at the end of Parrish Road near Brissette Beach. It was located on property owned by Nellie Marsh and her husband, and located just down the road from the Kuhn cottage. Ray paid the couple during the summer months to run electricity from their home to the stand.  Sharon Polzin at Big Bop's snack bar.

Sharon Polzin at Big Bop's snack bar.

Jack Kuhn started frequenting the Big Bop shortly after the club opened in 1957. It’s possible he heard about it that summer while running the popcorn stand at the beach. He loved rock and roll, and he was accepted by the kids at the club who knew nothing about his problems at St. James or with his father.

Kuhn was immediately impressed with Mickey Higgins and made every effort to form a friendship with him by staying after the Big Bop closed to help him clean up. In Jack’s eyes, Mickey was cool, popular, and successful – all the things he wished for himself.

Jack was at the Big Bop nearly every night it was open. White cotton jackets were in style at the time, and Jack’s had “Mickey’s Big Bop” stenciled on the back. His younger brother Mike claims that he would spend at least a half hour combing his hair before going to the club. Tall and lanky, Jack contrasted his slicked back hair style with Ivy League-style shirts and slacks. All of the people I interviewed for this story described Jack as a nice guy, well-mannered and neat, and everyone also vividly recalled the epileptic seizures he had at the club.

Mickey remembered that Jack never brought a girl to the Big Bop, but he danced all night long and would be wringing wet with sweat at the end of the evening. During a typical evening Jack would ask various girls to dance, but most often he would take part in group dances like The Stroll, or if it was a rocking song he would dance by himself in the crowd. It’s tempting to think of Jack Kuhn’s solo dancing as an unconscious attempt to exorcise from his being the twin demons of epilepsy and a judgmental father.

(L to R) Sharon Polzin, Colleen Sutter, Diane Pacynski, and friend on Midland St. in 1959

(L to R) Sharon Polzin, Colleen Sutter, Diane Pacynski, and friend on Midland St. in 1959

Ray Kuhn was not happy with the fact that Jack was spending so many nights at the Big Bop, and family dinners usually consisted of the two butting heads over the issue. Although he didn’t know Mickey Higgins, Ray felt that he was taking advantage of Jack. Ray had also heard rumors that Mickey hung around with some unsavory characters and that some of the activities at the Big Bop weren’t quite legal. He believed it would be in Jack’s best interest to stop going to the club and end the friendship with Mickey Higgins.

It's likely that Jack Kuhn knew how to yank his father's chain after dueling with him so many times over the dinner table. It's entirely possible that Jack exaggerated or even made up events at the Big Bop to get under his father's skin, thereby contibuting to the fallout that would eventually doom the club.

By the summer of 1958, Jack had incorporated music as part of his Brissette Beach popcorn stand. He borrowed 45s from Mickey and played his “Top 50” at the stand to attract customers. He probably met Emily Nelson there, and they soon started a relationship. When Emily discovered she was pregnant, Jack decided to marry her. According to Mike Kuhn, Ray was unhappy with the planned wedding, and that he complained that Emily came from a "trashy family" in West Branch.

Despite, or possibly because of, his father’s disapproval, Jack married Emily and moved out of the family home. He did not stop going to the Big Bop, but he kept his marriage a secret from everyone at the club, including his closest friend Mickey Higgins.

When Emily gave birth to their son John in April of 1959, Jack again concealed it from everyone at Mickey’s Big Bop. It seems obvious from his actions that he was in a loveless marriage. Jack took little interest in the infant, and he left Emily home to care for John while he went to the club by himself.

Things had changed at the Big Bop as well. Vivian Gardner had sold the restaurant and upstairs hall to Archie Snyder near the end of 1958, and moved out of the upstairs apartment where she lived with her husband. Snyder changed the name of the establishment to the U & I Restaurant, and Mickey and Pat, who now had a second daughter (Debbie), moved into the apartment that was located next to the club. The Higgins' apartment: (L to R) Sandy Short, her friend Jim, Pat Higgins, and Ruth Ann Carr

The Higgins' apartment: (L to R) Sandy Short, her friend Jim, Pat Higgins, and Ruth Ann Carr

It was at this time that Ray Kuhn sent a message to Mickey Higgins, via a third party, insisting that he keep Jack out of the Big Bop. Although he didn’t approve of Jack’s wife, he strongly believed his son should be at home with his family rather than staying out late at a dance club. Kuhn’s demand did not mention Jack’s marriage or child, however.

Mickey knew from prior conversations with Jack that Ray Kuhn was a powerful man, so he asked him if he would mind not coming to the Big Bop for a while, at least until his father cooled down. Higgins recalled, “Jack got all upset. He said he had no other place to go, the club was where he had fun, and he liked everybody there.” Looking back, Mickey said, “I had no good reason to keep him out. He wasn’t a troublemaker; all he did was dance and enjoy himself.” Jack did not reveal his secret of having a wife and child, and Mickey relented and let him stay. It would turn out to be a fateful decision.

Fed up with Jack’s continuing inattention, Emily began having an affair. The marriage came to what could have been a tragic end, on or around August 1st, when the unthinkable happened. Without notifying anyone, Emily abandoned the baby at home alone and left with her new boyfriend to live in Illinois. Jack had already left to spend the evening dancing at the Big Bop, and the 4-month-old infant was left unattended in his crib.

Later that night, a friend stopped by the house looking for Jack and heard the baby crying. When no one answered the door, he went in and found little John alone in the house. The friend averted a potential catastrophe when he wisely took the baby and some diapers to Ray and Helen Kuhn’s cottage on Brissette Beach.

Ray and his wife cared for John from that point on, and they were bitterly disappointed in Jack when he showed no interest in taking care of his son after his wife had left town. That was the final straw for Ray Kuhn. If Mickey Higgins was not going to stop Jack from spending his nights at the club rather than with his infant son, then Ray would put a stop to the Big Bop.

Kuhn’s first step was to submit a letter on August 17, 1959, to the City Commission, the governing body in charge of issuing annual dance licenses to businesses like Mickey’s Big Bop. The letter contained a list of charges claiming that the Big Bop was “a breeding place for crime frequented by hoodlums, ex-convicts, and probationers.” It also stated that “some youths carried switchblades and brass knuckles, the club was the scene of gang fights, and that it had the reputation among teenagers of being the worst dive in town”. These claims seem pretty outlandish considering that Higgins often employed off-duty police officers for security at the Big Bop.

It was also quite a coincidence that the Bay City police department submitted a recommendation to the City Commission that the club be denied an annual dance license or temporary dance permit that very same week, especially since the Big Bop had already been in operation for over two years. Police chief Frank Anderson stated at the meeting that his main objection was the club’s upstairs location. This, despite the fact that the club had two exits just like the many other upstairs halls and clubs that were currently in operation throughout the city.

The fact that Detective/Patrolman Roy Robb of the department’s Youth Bureau gave the club a clean bill of health at the meeting did not sway the majority of the Commissioners who voted 6 to 2 to deny the Big Bop its dance license. Ray Kuhn had a lot of political clout in Bay City. According to Mike Kuhn, the six Commissioners (Maurice Swartz, Otto Roth, Neil Meagher, Chester Urbaniak, J. Warren Wilson, and Phillip Dean) were all friends of Ray Kuhn and frequent guests at his home, as was Mayor James Tanner.

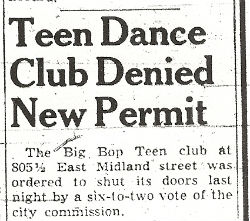

The following day the Bay City Times ran the story under the headline of “Teen Dance Club Denied New Permit”. Almost as damaging as the license denial was the adverse publicity the club received from the listing of all the trumped up charges in the Kuhn letter. Ray Kuhn’s name was not printed in the paper; however, as the article stated only that the charges came from “a Bay City father.” This was not surprising considering that Kuhn was the news editor at the Times, and no one was going to put his name in the story without his consent. The only response attributed to Mickey Higgins came in the article’s last sentence when he was quoted as saying “he intended to continue his fight to remain in business”.

Mickey could not operate the Big Bop after his license was denied, which in effect deprived him of his livelihood. Higgins hired a lawyer from Saginaw named William Ginster to represent him at the next week’s meeting. Mickey also brought a large delegation of teens from the club to address the Commission in defense of the Big Bop, along with a protest letter against the dance license denial signed by six hundred teens and parents who supported the club.

Their efforts were unsuccessful, however, and they failed to win a new hearing as the same six Commissioners again voted in opposition to granting a license to the club. The August 25th newspaper article went on to state that the delegation of teens was denied permission to address the Commission on the grounds that Ginster had failed to submit a written request for an audience by 4:00 p.m. Monday afternoon.

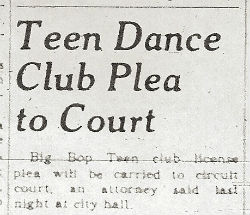

The City Commissioners could have allowed the teenagers’ voices to be heard under a provision allowing a suspension of Commission rules, but instead they chose to demonstrate to the youths how a democracy doesn’t always work for all of its citizens by hiding behind a technicality. Following the meeting, Ginster was quoted as saying he would “carry the license plea to circuit court in hopes of resolving the matter.”

On September 9, 1959, the Bay City Times reported that Mickey Higgins made an appeal at the Commission meeting that his application for an annual dance license to operate the club be reconsidered before the City Commissioners authorized the Big Bop’s permanent closing. Higgins invited the Commissioners and representatives of the Bay City Police Department to meet at the club on September 10th with a committee of teenagers and parents. They could inspect the Big Bop at that time and discuss rules and regulations under which it could operate if granted a license.

Attorney Ginster also presented a letter to the Commission that asserted the club would reopen under the new name of the Spinning Platter Teen Club, and it would operate strictly in accordance with a proposed dance ordinance to be drawn up by City Attorney John X. Theiler. The club promised off-duty police supervision, rules and regulations drawn up by a committee of parents and teenagers, adequate fire protection, and that no one would be admitted except card-carrying members, 14 to 19 years of age.

Despite the meeting, the inspection, and the concessions offered, the police department stand against the proposed reopening of the club remained unchanged. Their unfavorable recommendation was filed with the City Commission on September 14th, the date the club’s application for an annual dance license was scheduled for informal discussion by the Commissioners.

Imagine everyone’s surprise when the police department reversed their position at the September 21st meeting of the City Commission. The police report stated that they would now agree to a conditional permit to operate the teen club as long as certain conditions were met. These included the concessions stated in the Ginster letter of September 9th.

Clarence Comtois and Morgan Trudell were the only members of the City Commission who had consistently supported the Big Bop’s request for a dance license. After the police recommendation was read, Comtois resolved that Higgins be given conditional permission to operate the club according to the rules as set out by the police department report, and that the dance ordinance being prepared by Theiler be brought in as soon as possible.

Ray Kuhn’s supporters on the City Commission managed to keep the club closed despite the police department’s reversal; however, when Philip Dean led a successful move to table the recommendation until the new city ordinance regulating teen dance halls had been adopted. The passing of this amendment to the Comtois resolution would prove to be crucial to the eventual fate of the Big Bop/Spinning Platter.

In a recent interview, Mickey Higgins stated that he and Ray Kuhn had never met prior to Kuhn’s letter to the City Commission. Higgins said he tried to set up a meeting with Kuhn after his dance license was denied to see if they could settle their differences, but he refused to meet. Mickey claimed Kuhn was very vindictive, that everything in his letter was untrue, and that even his son Jack would have sworn to it. Jack Kuhn was nowhere to found, however. He hadn’t attended any of the City Commission meetings, and Mickey had not seen him since the Big Bop had been closed down in August.

The new teen dance hall ordinance had still not been approved at the October 12th City Commission meeting. When Kuhn’s cronies on the Commission again blocked a temporary permit for the Big Bop/Spinning Platter, Mickey said he was prepared to file a petition for a writ of mandamus in Circuit Court to force the Bay City Commission to grant him the right to re-open the club.

A mandamus is an order from a higher court to a lower authority (in this case the City Commission) instructing it to perform a specific action or duty.

Higgins filed the mandamus suit on the advice of his lawyer, William Ginster. Six weeks later, on December 1, 1959, Circuit Judge Richard G. Smith delivered the final crushing blow to the club when he dismissed the mandamus action and upheld the inherent police powers of the City Commission to grant or deny licenses until the long-delayed city ordinance to regulate licenses for teenage dances was written.

It would take City Attorney John X. Theiler over five months to complete the final draft of the ordinance that was presented to the City Commission on February 15, 1960. If he was stalling for time, it was an effective tactic. Mickey Higgins was out of money and tired of fighting the city. The prolonged six-month battle for the license had, for all intents and purposes, killed the Big Bop. The closing of the club was announced in the February 15th edition of the Bay City Times.

Looking back, Mickey believes that when the newspaper printed the contents of Kuhn’s letter, it had the desired effect of turning many parents against the club. Higgins says that adults in the 1950s didn’t approve of rock and roll and didn’t understand their kids’ love of the music; and the bad publicity in the paper made it worse. The printing of Kuhn’s claim that unsavory characters inhabited the club put a blemish on all the kids who went there.

Reading the ten Bay City Times articles that covered the Mickey’s Big Bop dispute, one is struck by the fact that none of them contain anything positive about the teen dance club. Was that because Ray Kuhn was the editor of the newspaper that was writing the stories? Didn’t anyone know that Kuhn was friends with both the Mayor and the Commissioners who were consistently voting against granting the Big Bop its dance license? It seems that conflict of interest and bias were issues that could certainly have been brought to light in this matter, not to mention slander if the charges in the letter were as false as Higgins asserted.

The collateral damage to Mickey Higgins was significant. Besides losing his business and the money he invested in the club, his marriage did not survive the stress that accompanied the turmoil over the Big Bop. Mickey and Pat divorced, and she moved with their two daughters to New England where she remarried. Pat then moved to Florida, and Mickey would have little contact with his two daughters from then on.

In 1961, Mickey entered the Lu Art Beauty School, located in the Cunningham Building on Washington Avenue in Downtown Bay City. He then attended the Detroit Barber College and worked as a barber in Dearborn until he moved back to Northern Michigan in the 1970s. In 1979, Mickey opened the Village Barber and Styling Shop in Harrisville, Michigan, and he has operated his business there ever since.

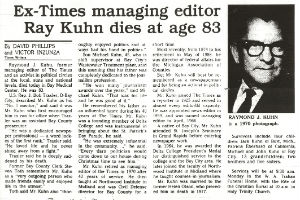

Ray Kuhn emerged from the Big Bop affair without a scratch. He continued to be an activist in political circles at the local, state, and even national level. Kuhn was awarded the Delta College President’s Medal for distinguished service to the college and the Bay City area in 1964. Two years later, he was named managing editor of the Bay City Times, a position he held until he retired in 1970, after 40 years of service to the newspaper.

Kuhn’s attack on the Big Bop failed in some respects, however, as its closing did not straighten out his son Jack nor mend their fractured relationship. When Jack failed to assume his paternal responsibilities to his son John, the boy was formally adopted by his grandparents Ray and Helen Kuhn. Then in a rather bizarre twist to the story, John Kuhn was brought up believing that he was the biological son of Ray and Helen, and that Jack was his estranged older brother.

Ray Kuhn died in 1988, but not before the 25th anniversary of Mickey’s Big Bop was celebrated on May 31, 1985, at the Prestolite Hall on Bay City’s West Side. The Bay City Times published two long articles that celebrated the teen club’s history. It must have been strange for Ray Kuhn to read the upbeat stories of the Big Bop; and that 250 people attended the reunion. Awash in 50’s nostalgia, there was no mention in either article of the controversial closing of the club by the City Commission or the scandalous allegations contained in Kuhn’s letter.  1985 Big Bop Reunion (L to R) Karen Daison, Jan Zacharko, Mickey Higgins, Patti LaLonde, Colleen (Sutter) Richter, and Sharon Polzin,

1985 Big Bop Reunion (L to R) Karen Daison, Jan Zacharko, Mickey Higgins, Patti LaLonde, Colleen (Sutter) Richter, and Sharon Polzin,

Jack Kuhn did not attend the reunion. Mickey Higgins never saw him again after the dance club closed. Higgins was shocked to learn, over fifty years later, that Jack had been secretly married while he was hanging out at the club; and that the abandonment of his child and issues he had with his father led directly to the infamous letter and the subsequent demise of the Big Bop.

Jack was never quite able to live up to his father’s standards, and their differences remained unresolved. This situation, along with the guilt he must have felt over his son John, probably contributed greatly to Jack’s life-long struggle with alcohol. He eventually went to work for General Motors and retired from the company, but he was estranged from his family for most of his life. Jack Kuhn passed away in 2007, taking to his grave the reasons why he didn't attempt to defend the club against the accusations of his father or make contact with Mickey Higgins during his ordeal with the Bay City Commission.

The enthusiasm for the Big Bop has not diminished over the years for those who were part of it. Everyone I contacted had fond memories of the club and Mickey Higgins. Many have his phone number, and Mickey says he still sees old members periodically. He recently ran into a couple celebrating their 50th wedding anniversary who first met at the dance club. Colleen (Sutter) Richter was a member right until the end. Like so many others, she warmly recalls Mickey’s Big Bop as “a wonderful place and the best time of my life.”  Former site of Mickey's Big Bop

Former site of Mickey's Big Bop

The research and interviews that were done to tell the story of the club has rekindled thoughts of yet another reunion. Sadly, several of the ‘Big Boppers’ who attended the 1985 bash are no longer living, but most still are and would undoubtedly enjoy another get-together. If they hold it in 2012, it would be the 55th anniversary of the opening of Bay City’s first teen dance club.

It would be nice if it could be held in the original upstairs hall at 805½ E. Midland Street, but that has long ago been converted into apartments. The great songs they danced to are still around, however, so somebody had better take their old records off the shelf because all of those former teens…….“Still like that old time rock n’ roll, that kind of music just soothes the soul. I reminisce about the days of old with that old time rock n’ roll.”  ohn R. Kuhn

ohn R. Kuhn

Afterword

John R. Kuhn, the son born to Jack and Emily Kuhn on April 4, 1959, died on Valentines Day, February 14, 2018. In his obituary, his grandparents, Raymond and Helen Kuhn, were listed as his parents. His biological father, Jack Kuhn, was listed as his predeceased brother. Emily Nelson Kuhn, his biological mother who abandoned him as an infant, was not mentioned in the obituary.