By Amy Kuperinsky | NJ Advance Media for NJ.com

A granite tombstone sat in Pam Nardella’s Elmwood Park backyard for eight years. It didn’t belong to anyone in her family, and it didn’t come with the house. In fact, no one was buried there. But there is a story. Really, two stories: one about the man whose name is engraved in the stone, and another about the stone itself.

“In memory of Frankie Lymon,” read the tribute, accented with a cross and flowers. “We ‘Promise to Remember.’”  Pam Nardella's flower garden

Pam Nardella's flower garden

In 1956, Lymon’s honeyed soprano voice made “Why Do Fools Fall In Love,” the debut single from Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, an instant hit. The song broke new ground for young artists, Black artists and rock ‘n’ roll.

Even though the New York doo-wop group had created a sound that would resonate for 65 years, the Teenagers were just starting their lives. Most of them were in high school. They had to finish their homework before recording the song. But Lymon, the lead singer, was just 13. It would be 12 more years before he died of a heroin overdose.

On Friday, the gravestone that bears his name was lifted from Nardella’s yard for a journey to its new home.

Where is it going? Why was it in New Jersey in the first place? Why does its plaque say “the official headstone of Frankie Lymon” if Lymon is buried beneath another stone in New York? “Why Do Fools Fall in Love?” might be a question with a simpler answer.  Teenagers 1956 (L to R) Joe Negroni, Herman Santiago, Jimmy Merchant, Frankie Lymon, Sherman Garnes Keystone/Getty Images

Teenagers 1956 (L to R) Joe Negroni, Herman Santiago, Jimmy Merchant, Frankie Lymon, Sherman Garnes Keystone/Getty Images

A voice that changed music forever, Frankie Lymon is buried at St. Raymond’s Cemetery in the Bronx. For many years, his grave was unmarked, says rock enthusiast Gary Johnson. Johnson took custody of the “official” headstone in Nardella’s yard Friday in order to send it to a museum in Michigan.

The move comes at a significant time, says Jimmy Merchant, an original member of the Teenagers. “This is absolutely a phenomenal reminder of a phenomenal moment in music history simply because Frankie Lymon and us did something the first weekend of this month in 1955,” says Merchant, 80.

The group recorded “Why Do Fools Fall in Love” the first Friday of December that year. By January, kids in school were singing the song between classes. Merchant laughs as he recalls the reaction of one student to Lymon’s soaring soprano: “You haven’t heard it yet??” they exclaimed. “They’re five white girls called the Teenagers!”  "Why Do Fools Fall In Love" 45

"Why Do Fools Fall In Love" 45

Marking the 65th anniversary of the song’s recording, Merchant proudly reflects on how the group started a youth movement in music that can be traced from their ‘50s harmonizing to the ‘70s hits of the Jackson 5, ‘90s boy bands and the current K-pop sensation that is BTS.“It was more than just a hit record,” he says. “It was a hit record by kids.” Boyz II Men inducted Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1993.

Frankie Lymon was 13 when he recorded the hit song "Why Do Fools Fall in Love" with the Teenagers.

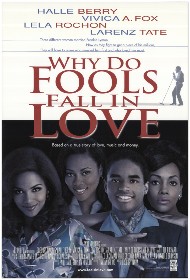

Lymon’s life, death and legacy became the subject of the 1998 movie “Why Do Fools Fall in Love,” starring Larenz Tate and Halle Berry. He joined the group in August 1955 after Merchant got together with the other members the previous spring.

Merchant and bass singer Sherman Garnes met at Edward W. Stitt Junior High School in Washington Heights and brought Herman Santiago and Joe Negroni into the fold. At first, they were called the Ermines. They would sing outside at 163rd Street and Edgecombe Avenue, near the school. Lymon, who lived across the street from Santiago, was never far away. “He was one of the kids that would stand and watch us,” says Merchant, a church minister who lives in the Bronx.

The group based the lyrics of “Why Do Fools Fall in Love” on a poem-slash-love letter a neighbor gave them. Merchant remembers working to incorporate lines like, “Why do birds sing so gay?” The song started off slow. When Lymon joined the group, they sped up the tune.

The teens headed into the recording studio at 10 p.m. that Friday in early December 1955. By about 1 a.m. Saturday, after 26 takes, they had it in the can and took a cab home. The song hit radio stations a few weeks later.

In 1956, the Teenagers would go on three tours in a single year, 60 to 91 days a pop, with a teacher joining them on the road. When they performed, they often wore white sweaters with red T’s on them — the industry guys wanted them to look like teenagers, Merchant says.

The group’s other 1956 releases included “I Want You to Be My Girl,” “The ABC’s of Love,” “I’m Not a Juvenile Delinquent” and “I Promise to Remember,” which is referenced on the tombstone in Nardella’s yard.  Frankie Lymon

Frankie Lymon

It wasn’t long before Lymon was separated from the group in the interest of making him a solo artist. All told, they were only together for a year and a half. The memory is bittersweet. This is one side of what Merchant calls the “sad part.”

The other was — and is — infuriating. Each singer was told they would receive writing credit and royalties from “Why Do Fools Fall in Love” when they turned 21. That’s not what happened. While Lymon’s name was on the record, Merchant and the others were frozen out. Record label boss George Goldner slapped his name on the song. So did his successor, Morris Levy. They made money, unlike the group members. Merchant and Santiago fought back in court for years.

The stone has spent 30 years in New Jersey. Now Johnson is bringing it to a Michigan museum to help celebrate the history of rock 'n' roll. Johnson, 74, first heard about the New Jersey gravestone when he bought a Weird N.J. book as a housewarming gift for his son and daughter-in-law, who live in Roselle.

The book had a story about the Lymon tombstone residing at Ronnie I’s, a Clifton music store owned by Ronnie Italiano. Lymon’s “fans and friends” had dedicated the stone for the 20th anniversary of his death in 1988.For more than 20 years, the tombstone was in the window of Ronnie I's Clifton Music. “It sat in the store, in the window, forever,” says Nardella, 74.

The shop was solely dedicated to doo-wop, or as Italiano preferred to call it, “vocal group harmony.” Italiano was the founder of the United in Group Harmony Association, which hosted hundreds of shows that would unite fans of doo-wop with the old-school acts they treasured. The gigs, held at Schuetzen Park in North Bergen, were so informal that people would mingle with the talent, says Nardella, who became one of Italiano’s DJs.  Ronnie Italiano at Clifton Music

Ronnie Italiano at Clifton Music

After he found out that Lymon’s grave was unmarked, Italiano organized a benefit concert that generated the funds necessary for a fitting tribute.

Johnson, who lives in Michigan with his wife but has an apartment in Rahway, decided to make the trip to New Jersey to meet Italiano and visit the tombstone. The retired middle school teacher is so devoted to anything that rocks and rolls that he started a rock history class for his school in Essexville, Michigan, and wrote a related textbook.

But Italiano died in 2008, at 67, and UGHA fizzled out, says Nardella, known as Dreamgirl DJ. When Ronnie I’s closed in 2012, Italiano’s widow asked her to take Lymon’s tombstone. Nardella didn’t want to see the tribute destroyed, so she got a monument company to put it in her garden.

When Johnson heard about Italiano’s death, he wondered what had become of the memorial. In 2011, he wrote about the shop owner and gravestone in his blog at the Michigan Rock and Roll Legends Hall of Fame, a website he runs that recognizes the talents of the Great Lakes State.

Nicky Addeo read Johnson’s blog post. Addeo, an Asbury Park singer who has performed alongside Bruce Springsteen — who is himself a fan of “Gloria,” Addeo’s 1963 doo-wop song with the Darchaes — sent the Michigander an email. The singer, who had played UGHA shows, put him in touch with Nardella. “When I found out it was in someone’s backyard, I couldn’t believe it,” Johnson says.

“He said he wanted to borrow it,” Nardella says. “I said it’s 1,500 pounds.” She had installed drive-in movie speakers on each side of the stone to match the ‘50s theme. In warmer months, it was surrounded by irises and pink flamingos. “Every year I’ve had a tombstone barbecue in July,” says Nardella, who works in marketing for an insurance agency. The first time, 100 people from UGHA showed up. “It’s a piece of history,” she says. “We consider it the original tombstone because there was nothing until this.”  Pam Nardella and Gary Johnson

Pam Nardella and Gary Johnson

On Friday morning, Johnson and Nardella were there when Butler’s Monroe Monuments removed the stone from its resting place. Merchant wanted to be there, too, but he decided that making the trip would put him and his wife at greater risk for COVID-19.

The tombstone’s destination: the Michigan Rock and Roll Legends Hall of Fame exhibit at the Historical Museum of Bay County in Bay City, Michigan. Johnson, who is on the museum board, was invited to curate the section after hosting similar displays at city businesses.

“Our main claim to fame is that it’s the birthplace of Madonna,” he says of Bay City. (He’s working on getting in touch with her father.) While Lymon doesn’t have a biographical link to Michigan, Johnson draws a direct line between the Teenagers and groups like the Supremes and Berry Gordy’s Detroit-based Motown roster.

So what’s the story with the other Frankie Lymon tombstone, the one that actually marks his grave? And why did it materialize so long after his death?

Frankie Lymon's gravesite at St. Raymond's Cemetery in the Bronx. For many years, the grave had no headstone. When Italiano first thought of hosting a benefit to raise money for the headstone, he consulted Lymon’s widow, Emira Eagle. She married the singer less than a year before he died in 1968, at 25. Eagle was onboard with the fan effort, which brought in $3,000 for the memorial. But when it came time to place the stone, she had other plans.

The tribute clashed with another part of Lymon’s legacy: the legal battle over his song royalties. Complicating matters was the fact that two other women — Elizabeth Waters and Zola Taylor, a singer from The Platters — claimed to have been married to Lymon before his death (he had apparently never divorced any of his wives). In the 1980s, Eagle, Taylor and Waters went to court to seek money owed to the singer’s estate. The popularity of Diana Ross’ 1981 cover of “Why Do Fools Fall in Love” raised the stakes.

The legal conflict is central to the 1998 movie of the same name about Lymon and his widows. In the film, Lela Rochon plays Eagle opposite Larenz Tate as Lymon, Halle Berry as Taylor and Vivica A. Fox as Waters.

Johnson says that in the tangle of trying to determine who would be legally entitled to Lymon’s royalties, Eagle decided that it would be better if she provided a tombstone for the singer. “In Loving Memory of My Husband Frank J. Lymon,” reads the headstone at St. Raymond’s Cemetery in the Bronx. (Eagle died in 2019.)

Meanwhile, no one seemed to want the fan-sponsored tombstone, Nardella says — not the Smithsonian and not the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. She’s glad the tribute has finally found a new space. “It should be in a museum where people can go see it,” she says. “It doesn’t belong in my yard. It’s too bad that it’s not in New York, but what are you gonna do?”

Source: New Jersey Star-Ledger - December 11, 2021