At the time of Frankie Lymon’s death, classic doo wop music had been replaced on the charts for over four years. The arrival of the Beatles and the other British Invasion artists had shifted the music dynamic not only on radio stations and in record stores, but also in the performance arena. It was now much more fashionable and lucrative for young people to buy instruments and form bands to play the hits of the day rather than joining vocal harmony groups and sing songs that appeared to be part of the past.

Although doo wop seemed to be increasingly relegated to a bygone era, its harmonic roots could be heard in the many hits of Motown groups, including the Miracles, Four Tops, Supremes, and Temptations, as well as many other successful soul music artists of the 1960s. The groups that had defined the era, however, had all but disappeared from the Billboard charts and radio station playlists as the decade drew to a close.

The fact that the classic doo wop sounds of the 1950s and early 1960s continued to be loved and appreciated despite its fading commercial appeal had a lot to do with the people who grew up with the music. All music has the power to bring back memories. A song heard at a specific moment in time and then not heard again until a later date can give a person a sense of nostalgia for the time remembered and the events associated with it.

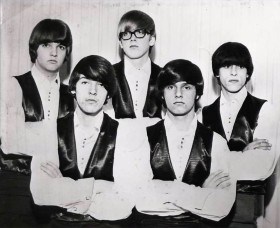

Doo wop has an innocent sound. Think back to your very first love; that’s what a great doo wop ballad felt like. It was that all-encompassing feeling, one that will seemingly burn you up if goes any further. The greatest of those ballads sounded almost virginal and pure, like true love, with lyrics that conveyed what a young person was feeling but may have been too tongue-tied or shy to express. Romantic longing and emotions are universal, and it helps explain why classic doo wop remained in the hearts of many during the late 1960s and beyond.  The Castiles: Springsteen front left

The Castiles: Springsteen front left

This seemed to be particularly true on the East Coast. In his Born To Run memoir, Bruce Springsteen wrote about his high school band, the Castiles, playing teen dances in New Jersey. The band often played gigs at one of the teen nightclubs or dance halls along Route 9, south of Freehold, New Jersey.

Many of these venues were ruled by a largely Italian teen subset called “greasers” because of their extensive use of hair products. Doo wop was their music of choice, and Springsteen recalled that, even though the Castiles were formed in the wake of the British Invasion, they had to be able to sing a handful of doo wop standards like “What’s Your Name” and “In The Still Of The Nite” in order to survive those gigs.

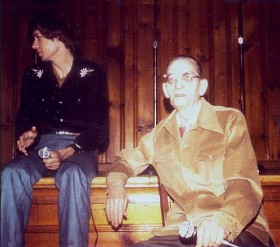

Vocal group historian Donn Fileti points to the legendary Times Square Record Shop and its proprietor, Irving “Slim” Rose, as being a major force in the continuing popularity of the doo wop sound in the 1960s. Fileti credits Rose with coming up with the idea of buying the masters and reissuing older vocal group singles from the 1950s like “Baby Oh Baby” by the Shells, “Rama Lama Ding Dong” by the Edsels, and “There’s A Moon Out Tonight” by the Capris, all of which became national hits early in the new decade.  (L-R) Donn Fileti and Slim Rose

(L-R) Donn Fileti and Slim Rose

Fileti also attributed to Rose the clever idea of releasing vocal group rehearsal demos, recorded without the requisite musical accompaniment, as acapella 45s and thereby creating a new sub-genre for record collectors.

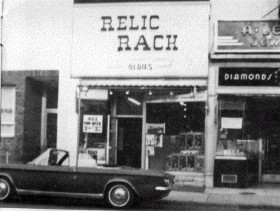

Sales dwindled with the onset of the British Invasion, and Rose sold the Times Square Record Shop and all its masters to Fileti and Eddie Gries, owners of the Relic Rack store in Hackensack, NJ. The pair formed the Relic label and, driven by their shared love of vocal group harmony, they started releasing albums of acapella anthologies featuring obscure performances by groups like the Zircons, Nutmegs, and Velvet Angels. Sales were very slow for the first few years because they were swimming against the tide of, what Gries described as, “the mass brainwashing of the public with imported English garbage.”

By 1968, there were probably very few people, even among enthusiasts, who believed that doo wop would, once again, become a force in the music business, but that’s exactly what occurred. A combination of factors allowed this to happen, and some recordings by seemingly unlikely artists may have started the ball rolling.

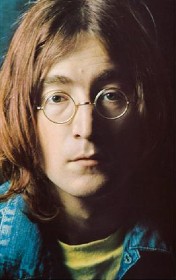

The first came compliments of the Beatles. Although they were inadvertently responsible for doo wop's demise, the Beatles were big fans of 1950’s rock and roll and covered songs by girl groups like the Shirelles, Cookies, and Marvelettes on their early albums. In late November 1968, they released “The Beatles” (a.k.a. “The White Album"), a fascinating double album containing 30 songs, all composed by members of the band. The songs displayed a wide variety of styles and influences and further solidified their status as the main arbiters of what was cool.  John Lennon

John Lennon

Two songs on the album included definite doo wop references. The first, John Lennon’s “Revolution 1”, included Paul McCartney and George Harrison singing the nonsense lyrics 'bom-shooby-doo-wop' in the background.

The more interesting of these, however, was Lennon’s “Happiness Is A Warm Gun”. It was composed into three distinct sections, the last, starting at the 1 min. 34 sec. mark, was done in classic doo wop style, including a recitation by Lennon. In addition, the 'bang-bang, shoot-shoot' backing vocals by McCartney and Harrison were another clever tip of the hat to the group harmony genre.

“The Beatles” album was an enormous success in the United States, spending nine weeks at # 1 on the Billboard Top 200 and selling over 12 million copies. Listen to "Happiness is A Warm Gun."

The second recording that planted the seeds of the doo wop revival was not nearly as successful commercially, but it managed to achieve the seemingly impossible task of appealing to both the audience for experimental rock as well as fans of classic doo wop. The Mothers Of Invention was a rock band from California, led by Frank Zappa, that gained popularity and critical acclaim for the sonic experimentation on their early albums and for their elaborate stage shows.

While recording their third album, “We’re Only In It For The Money”, the band members began discussing their affection for the vocal group songs that were popular during their high school days; and Zappa suggested recording a doo wop album as a fictitious Chicano band called Ruben & The Jets.

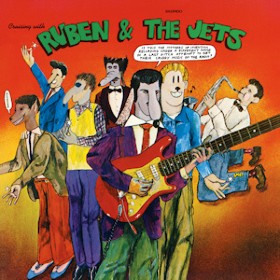

Back in 1963, Zappa and the band’s lead singer Ray Collins wrote “Memories Of El Monte”, featuring the lead vocals of Cleve Duncan of the Penguins. Done in classic doo wop style, the song reminisces about the dances held at the El Monte Legion Stadium and the artists that performed there. That songwriting experience, along with Collins’ high falsetto, enabled them to produce an album in 1968 that worked both as a satire and as a homage to the 1950s vocal group music that they loved.  Frank Zappa's Ruben & The Jets LP

Frank Zappa's Ruben & The Jets LP

Released two weeks after “The Beatles” LP, “Cruising with Ruben & The Jets” makes no mention of the Mothers Of Invention on the cover except for a word bubble above the cartoon illustration of the band as anthropomorphic dogs.

The album works as a doo wop release because Zappa and the band played it straight, not letting the satire get in the way of the 13 songs, many of which sounded like they could have possibly charted back in 1958. Although it was not a big hit, it was popular with radio stations, and some even believed that they had discovered a lost doo wop album by an unknown band called Ruben & The Jets. Listen to "Anything" by Ruben & The Jets.

The hard rock scene in Detroit had blossomed out of the Grande Ballroom and produced a number of young bands. These included the MC5, the Amboy Dukes, the Frost, the Bob Seger System, SRC, and the Stooges, all of whom signed recording contracts with national labels in the late 60s.

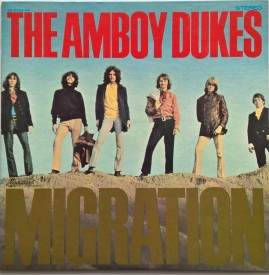

The Amboy Dukes got their name from a 1948 novel by Irving Shulman about a teenage gang from a tough section of Brooklyn. The band was best known for the howling lead guitar of Ted Nugent, but they did a complete about-face on one song from their third album, “Migration”. Released in 1969, it included an excellent cover of Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers’ “I’m Not A Juvenile Delinquent," featuring a flawless lead vocal by keyboardist Andy Soloman.  Amboy Dukes' Migration LP

Amboy Dukes' Migration LP

Although the song was probably recorded because of its connection to the delinquent street gang that inspired the band’s name, it served to introduce doo wop to many young, long-haired music fans in the Motor City and beyond. It is also interesting that Morris Levy was listed on the album as one of the songwriters for “I’m Not A Juvenile Delinquent” in place of George Goldner. Listen to "I'm Not A Juvenile Delinquent" by the Amboy Dukes.

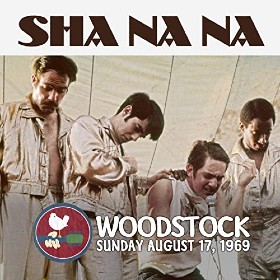

The three-day Woodstock festival, held in Bethel, New York, on August 15-17, 1969, was a pivotal moment in popular music history and a defining event for the counterculture generation of the 1960s. Positioned as a rejection of the conformity and restrictive moral values that were popularly ascribed to the 1950s, it seemed an unusual event for an act that celebrated the styles, symbols, and sounds of the decade in which doo wop played such an important role.

Sha Na Na was a Columbia University acapella group turned 1950’s revival act. The group took its name from some of the nonsense lyrics of “Get A Job”, the 1958 # 1 doo wop hit by the Silhouettes. Appearing in greaser hairdos and cast-off costumes from a traveling production of Bye Bye Birdie, Sha Na Na played a set of 50’s covers at Woodstock including “Yakety Yak” by the Coasters, Elvis Presley’s “Jailhouse Rock”, and “At The Hop” by Danny and the Juniors.

The band had gained a reputation for their “greaser” revival shows in the New York area, and they were invited to be Jimi Hendrix’s opening act at Woodstock. Hendrix had seen one of their shows and described them to festival organizers as being “far out.” Judging by the reaction shots of the crowd in the Woodstock documentary, Sha Na Na’s performance was initially disorienting, but they were eventually received warmly by the festivalgoers.  Sha Na Na at Woodstock

Sha Na Na at Woodstock

Their appearance became much more important when a 90-second segment was included in Woodstock, the Academy Award-winning documentary of the festival. In addition, their rendition of “At The Hop” was also one of the songs featured on the triple album, “Woodstock: Music from the Original Soundtrack and More." Released nine months after the festival, the album spent four weeks at # 1 and sold over 2 million copies.

More success was on the way. Two months after Woodstock, Sha Na Na released their first album, “Rock and Roll Is Here To Stay”, that featured covers of numerous doo wop classics including “Remember Then”, “Come Go With Me”, and “Book Of Love”. They were also one of the acts in Richard Nader’s first Rock and Roll Revival concert along with Chuck Berry, the Platters, Bill Haley and His Comets, the Shirelles, the Coasters, and Jimmy Clanton.

Nader was an entertainment promoter who initially came up with the idea of packaging concerts with the oldies acts he loved back when the British Invasion was in full swing. After failing to convince established promoters of the profitability of his concept, he borrowed $35,000 and, on his own, rented the Felt Forum at Madison Square Garden.

The early and late shows of his Rock and Roll Revival each attracted a sold-out crowd of 4,500, and Nader was off and running. Over the next decade, he would present 25 more oldies shows at the Garden, drawing a total audience of nearly half a million. Nader went on to present oldies concerts all over the United States and Britain; and he produced the 1973 documentary film, Let The Good Times Roll, that included performances from shows at the Nassau Coliseum on Long Island and Cobo Hall in Detroit.

As important as Richard Nader was in demonstrating the commercial value of 1950's nostalgia, it was a radio program that brought about a doo wop renaissance in New York, Connecticut, and New Jersey.

In the fall of 1969, it was announced that WCBS 101.1 FM would become New York’s sixth rock station. Program director Gus Gossert said that the sound of the station would now be half hit singles and half album cuts. Following a listener’s suggestion, however, Gossert began hosting an oldies’ show on Sunday nights, but he was only playing the hit songs of the 1950s like “Lipstick On Your Collar” by Connie Francis and “Rockin’ Robin” by Bobby Day.  (L-R) Wayne Stierle, Gus Gossert, Stan Krause

(L-R) Wayne Stierle, Gus Gossert, Stan Krause

Gossert’s oldies show didn’t take off until he was contacted by doo wop fans Wayne Stierle, Stan Krause, Chris Marko, and Bill Olb. They convinced him that New York oldies was centered on vocal harmony groups and that he should be featuring those records on his program. Several weeks later, Gossert invited the four of them to the WCBS studio.

Stierle, Krause, and Marko put together Gossert’s new playlist that now highlighted vocal harmony group records. Olb, who had an encyclopedic knowledge of the genre from his years of pouring through the microfiche files of Cash Box magazine at the New York City Library, provided the historical information about the groups and the recordings for the broadcast. This combination saw immediate results as the audience increased dramatically for Gossert’s Sunday night show, more than doubling the ratings for any of the station’s other programming.

Despite the popularity of Gossert’s show, all was not well at the station. Bill Olb recalled that WCBS executives couldn’t understand or appreciate doo wop. “Although the show was very popular, it also became political since Gossert’s show was more successful than the other rock programming, and it was making some people at the station look bad,” Olb said.

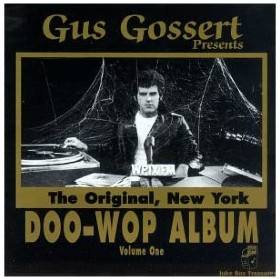

As a result of the infighting, Gossert was let go from WCBS. He immediately signed with WPIX-FM in New York, and his 7:00 to midnight shows on both Saturday and Sunday nights became immensely popular. During this time, Gossert had the highest-rated program in New York radio.  Gossert's first doo wop album

Gossert's first doo wop album

His newfound celebrity status enabled him to put out a number of vocal group albums including the very successful “Gus Gossert Presents, The New York Doo Wop Album Vol. 1” that featured selections from Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, the Five Satins, the Shells, the Quotations, and the Students. Bill Olb was listed as an inspiration on the back of the album cover.

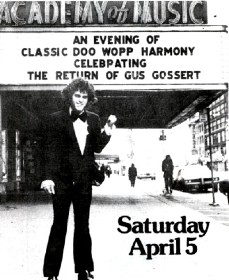

Gossert also started presenting oldies shows at the Academy of Music, a 3,000-seat movie theater on 14th Street in Manhattan that was used for rock and roll concerts in the 1960s and 1970s. “There were two shows per night and they always sold out,” Olb recalled. “He presented some of the top vocal groups at the concerts including the Harptones, the Chantels, Johnny Maestro and the Crests, the Jesters, and the Five Satins.

Well-paid because of his radio success in the lucrative New York market, Gus Gossert lived in an impressive apartment near 60th Street and Columbus Circle, west of Central Park, and he loved to throw elaborate parties. He also had a dark side, however, which led to his eventual arrest for dealing cocaine and the end of his career in New York.

“Gossert was convicted in 1973, but because he was a first-time offender, he did not receive a long prison sentence,” Olb recalled. “He might have spent 90 days in prison and was then placed on probation.”  Scene of Gossert's murder

Scene of Gossert's murder

By 1976, Gossert was looking for a new start. He moved to Tennessee where he found a radio job at station WOKI in Oak Ridge. In August, however, he was found dead his car in a deserted rural area. It looked as if someone had shot him from the passenger seat and then simply disappeared. The murder case was never solved, but it had all the earmarks of a drug deal gone bad.

While Gossert was becoming the “king of the oldies” at WPIX-FM, his former station WCBS-FM and its contemporary rock format continued to flounder in the ratings. In 1972, the station did a complete about-face by firing the executives who championed contemporary rock and switching to an all-oldies format.

The following year, with Gossert off the air, WCBS-FM attracted the audience for a weekend doo wop program with the Nite Train Show, featuring DJ Norm N. Nite. When Nite left to join WNBC in 1975, his Sunday night spot was taken over by Don K. Reed. The program’s name was changed to The Doo Wop Shop, and it stayed that way until the program was cancelled in 2002.

Although Gus Gossert is often credited with popularizing the term ‘doo wop’ to describe the vocal group harmony records that were featured on his broadcasts, the term first appeared in print in 1961 in a Chicago Defender article about “Blue Moon” by the Marcels. To his credit, Gossert declined to take unwarranted credit for the term, and his first album of vocal harmony group recordings contained this quote: “The word ‘Doo Wop’, like the word ‘Oldie’, is only a term,” Gossert wrote. ‘The ‘Sound’, whatever you prefer to call it, means memories and love, and in the long run, that’s what it’s all about.”

Gus Gossert’s show helped revitalize doo wop music in the New York area in the early 1970s, and it provided a vital listening experience for its many fans, especially one named Ronnie Italiano.  The Relic Rack in Hackensack, NJ

The Relic Rack in Hackensack, NJ

Bill Olb recalled that he first met Ronnie in 1970 at the Relic Rack record store in Hackensack, New Jersey, where Olb worked part-time. “The store was famous for its oldies and had a ‘money record wall’ that displayed records that were worth $10 and up,” Olb said. “Ronnie purchased a couple of rare vocal harmony group records, “You’re Mine” by the Crickets and one by the Royals on the Federal label.”

“We talked because not a lot of people would come in and spend $100 on old records, and I told Ronnie about my involvement with Gus Gossert’s Sunday night show on WCBS-FM,” Olb said.

After listening to Gossert’s program, Ronnie starting going to the Relic Rack each week looking for hard-to-find harmony group records, and he and Olb started meeting at Ronnie’s home to talk music and share their passion for vocal groups.

“He had a history of being a DJ at East Rutherford High School dances where he lived in New Jersey," Olb said. “It was very Italian and doo wop was the big music.” Ronnie, who was six years older than Olb, was active in the music until 1964. “He had between 900 and 1,000 records in his collection, but he stopped buying music after the British Invasion which he didn’t like,” Olb said.

“Ronnie got married in 1963 and started a family. He was driving truck at this time, delivering soda to stores,” Olb recalled. “Seven years later, he heard Gus Gossert’s show on WCBS-FM in New York and he got back into the music in a big way.”  Gus Gossert - Academy of Music

Gus Gossert - Academy of Music

Besides sharing a love of vocal group records, Ronnie and Olb also attended several of Gossert’s oldies shows at the Academy of Music Theater. Olb kept the programs from the concerts that featured a who’s who of great vocal groups including the Nutmegs, Ben E. King and the Drifters, the Dell Vikings, and the Cleftones.

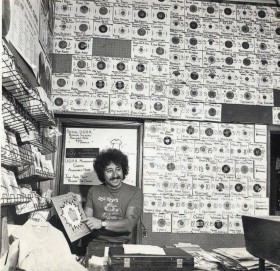

“On January 22, 1972, Ronnie Italiano bought Clifton Music,” Olb remembered. “The store had opened in 1950, but the couple that owned it wanted to retire. It was not an oldies’ shop at that time. It was a music lesson store that sold current music along with a few oldies, but not vocal group stuff. Ronnie turned it into one of the largest oldie vocal group stores in the country within ten years,” Olb said.

In 1973, Ronnie was invited to be a guest on a radio show in NYC. The following year, he took over the show, now called Ronnie I Just For You. “When he started broadcasting, Ronnie came to my house, where I had some equipment, and we would tape the shows on reel-to-reel,” Olb recalled. “At this time, I worked part-time in his music store because I was employed full-time as a financial officer in a bank.”  Ronnie Italiano at Clifton Music

Ronnie Italiano at Clifton Music

Ronnie started the United in Group Harmony Association (UGHA) in 1976, and the early meetings were held in his basement. The UGHA had its first meeting show on December 3, 1976, at the American Legion Hall in East Rutherford. “They moved around because people didn’t understand the kind of shows Ronnie was running. Some members came to the shows in motorcycle jackets with hair slicked back like it was the 1950s. Their appearance upset the older people in the neighborhood who didn’t want that element there,” Olb said with a laugh.

From those humble beginnings, Ronnie's UGHA would go on to become a major force in the preservation of vocal harmony group music with over 2,000 members worldwide. It was also important for its role in the revival of a number of storied vocal harmony groups, a list that included the Teenagers.

Three weeks after Ronnie I purchased his record store in Clifton, the musical Grease began its Off-Broadway run. The popular show was set in 1959 and featured a host of original songs written in the styles that drew upon the sounds of early rock and roll and doo wop. The humorous plot subverted many of the tropes of 1950’s rock and roll movies, and the hit show was nominated for seven Tony Awards in 1972.

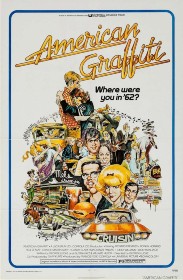

As important as Grease and the UGHA were to the rekindling of interest in doo wop music in the New York/New Jersey area, it took a hit motion picture to spread it all across the country. American Graffiti was the first film to effectively use rock and roll music, and especially doo wop, to establish a particular time and place, in this case a single night in Modesto, California in 1962.

George Lucas’ film used a wall-to-wall soundtrack of early rock and roll songs to recapture the attitudes of the period, particularly the innocence that Vietnam, Lee Harvey Oswald, hard drugs, birth-control pills, the Manson Family, and Richard Nixon had altered, and perhaps destroyed, forever.

Even though the action took place in 1962, the film opened with 1955’s “Rock Around The Clock”; and the rest of the movie is dominated by songs that were released prior to 1959. Of the songs on the “41 Original Hits From The Soundtrack Of American Graffiti”, 21 were doo wop songs. The immensely popular 2 LP soundtrack was certified triple platinum in the United States, where it peaked at # 10 on the Billboard 200 album chart.

It’s also interesting to note that 10 of the 41 songs were controlled by Morris Levy and Roulette Records. Levy’s name was listed as a songwriter on two of the songs, Lee Dorsey’s “Ya Ya” and “Why Do Fools Fall In Love” by Frankie Lymon and The Teenagers. The songs on American Graffiti's soundtrack didn’t merely provide setting and atmosphere by using pre-British Invasion doo wop, rock, and R&B, they also help set a mood for the film of carefree, innocent youth, a time that had no apparent connection to the war and protests that dominated the news media in the early 1970s.  American Graffiti Soundtrack LP

American Graffiti Soundtrack LP

The doo wop songs were very effective in conveying that mood and keeping the viewer located in a time and place that was gone while also using them to recapture and celebrate an idealized era and, at the same time, lament the loss of American innocence. This was the point where the original groups and their music leapt back into the mainstream.

These extramusical associations, held in the memories of American Graffiti’s audiences, also opened up interpretive possibilities that the film’s visual elements did not provide. “Why Do Fools Fall In Love” was used in one of the film’s most memorable scenes when Curt (portrayed by Richard Dreyfuss) first spots his dream girl (Suzanne Somers) driving a white T-Bird.

The selection of this particular doo wop song, rather than any of the innumerable songs from the era about falling in love, might suggest that Curt is the song’s titular “fool,” providing commentary on the scene’s action and Curt as a character. “Why Do Fools Fall in Love” relied heavily on Frankie Lymon’s soprano vocals, which communicated innocence, precociousness, and enthusiasm. These same qualities could be read onto Curt in this scene, and help to suggest that he was being foolish and that his dream girl was a figment of his romantic imagination.

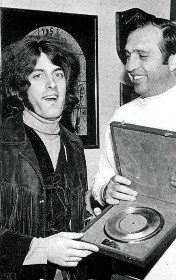

Artistic interpretations aside, the use of “Why Do Fools Fall In Love” in the hit film put Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers back on the charts 17 years after their song had helped change the music business.  Tommy James & Morris Levy

Tommy James & Morris Levy

One thing that had not changed over those years was the reluctance of Morris Levy to pay out royalty statements, unless, of course, that royalty went to a song that Levy’s writing credit appeared on. “Why Do Fools Fall In Love” was credited to Frankie Lymon and Morris Levy, but apparently no money had been paid to Lymon’s estate despite the song appearing on several oldies collections issued by Roulette, the cover versions recorded by other artists, or the hit American Graffiti soundtrack.

Tommy James, who charted 31 songs on the Roulette label from 1966 to 1973, wrote extensively about his relationship with Levy and the difficulty of getting paid in his entertaining memoir, Me, The Mob, And The Music. “The big joke at Roulette,” James wrote, “was that scientists were trying to find the quietest place on earth. Their answer: The Royalty Department at Roulette.”

The songwriting and publishing royalties for “Why Do Fools Fall In Love” would eventually be addressed in the 1980s through a series of trials. The results of those court cases would affect not only Morris Levy and the three women claiming to be Frankie Lymon’s rightful heir, but also Ronnie Italiano, the UGHA, and the surviving members of the Teenagers.

End of Part 3