By 1993, Ronnie I’s Clifton Music store had become a New Jersey institution, known around the world by aficionados of the vocal group harmony sound. Ronnie had come a long way in the two decades since he quit a steady job driving truck for PepsiCo to purchase a music store with a pregnant wife and two young daughters to support.

He loved the group harmony sound, and Ronnie brought acapella to the forefront during those years. “Good music, simple, beautiful music; the kind that touches your heart – there’s nothing like it,” he told a Japanese film company that came to Ronnie I's Clifton Music. “When you’re feeling down and feeling sad, it brings you up. The kind of music that I can really relate to is acapella music. Five beautiful voices coming from the streets. The human voice, the most beautiful instrument of them all.”

“When you go back to like 1953, the local DJs in the New York City area were playing a new form of music. They called it rock and roll, and every kid emulated this music through acapella on the street corners of this area,” Ronnie recalled. “Think about it. It’s 1993, 40 years later, and we still have the beautiful sound of acapella.”

Ronnie I's Clifton Music with Frankie's Tombstone in window

Ronnie I's Clifton Music with Frankie's Tombstone in window

The man and the music he loved had attracted the Japanese company to travel to New Jersey in 1993 to film a documentary that included interview footage of Ronnie as well as acapella performances from contemporary doo wop groups including Choice, the Delmonicos, and the Brooklyn Connection. By that time, Ronnie was recognized as a leading authority on the genre, and he had turned Clifton Music into one of the largest oldie vocal group stores in the country.

Ron Italiano Jr. was born shortly after his father purchased the store. He grew up in East Rutherford, NJ, with his older sisters Doreen and Tammi. As he grew older, Ron Jr. began spending more time in the store, and he watched as his father slowly converted it from a business that sold instruments into a record store that focused on his passion – vocal harmony group music.

Diane Italiano was supportive of Ronnie’s purchase, but his wife wasn’t into the music like he was. She was a hard worker and, according to Ron Jr., the kids always came first. Diane worked two jobs as a hairdresser during the day, and she worked as a waitress at night to help support the family.

Ron Jr. recalled that his father had a man cave in the basement that had all his records. "Music was constantly playing in the house and even in the car," he said. "My father wasn’t a good singer, but he always sang along with the records. He had a great ear, however, and he later used it to produce quite a few vocal harmony group recordings, many on his own Clifton label."

One of Ronnie I’s first important ideas was the formation of an organization that would promote vocal group music. The United in Group Harmony Association (UGHA) was founded by Ronnie in 1976, and the first monthly meetings were held in the basement of his home in East Rutherford. The non-profit, tax-exempt organization was dedicated to the preservation, exposure and education of authentic vocal group Rhythm and Blues/Rock and Roll music.  United In Group Harmony Association

United In Group Harmony Association

The basement meetings soon evolved into show meetings that featured vocal group performances. According to a history written by UGHA member Jerry Skokandich, the first of these was held on December 3, 1976, at the American Legion Hall in East Rutherford and featured a performance from the Bon-Aires.

Three months later, the meetings were moved around the corner to Mercury Club for the next six shows. As the meetings grew in size, they were moved once again to the St. Joseph’s Church Auditorium, and this would become the UGHA’s home for the next two years.

As UGHA’s family of supporters expanded beyond the New York City metropolitan area and started attracting members from across the country, the need for a larger meeting space prompted a final move, this time to a banquet hall named Scheutzen Park in North Bergen, NJ.

Skokandich wrote that the UGHA’s greatest accomplishments were the preservation of vocal group music and its efforts to pay tribute to the pioneer R&B artists all but forgotten by the rest of the world. The UGHA eventually attracted over 2,000 members worldwide and was responsible for the revival of storied groups like the Teenagers, Cadillacs, Solitaires, Lillian Leach and the Mellows, Five Keys, Golden Gate Quartet, Moonglows, Nutmegs, Chantels and many more. According to Skokandich, over 1,000 groups graced the UGHA stage over the years.

Although the UGHA shows were memorable, they often failed to break even. “My dad was the worst businessman you ever met in your life because he never did anything to make money – he did everything for the music,” Ron Jr. recalled. “He didn’t care if he lost money on the shows. He just wanted to do what he loved and bring music out to everyone else. His favorite thing in the world was to bring these old vocal harmony groups, who didn’t think they had an audience anymore, to the UGHA. They would almost be in tears because they couldn’t believe that there still were people who loved their talent and what they could do.”  Ronnie Italiano 1958

Ronnie Italiano 1958

When Ronnie I was growing up in East Rutherford in the 1950’s, he listened to New York DJs like Tommy "Dr. Jive" Small on WWRL and Alan Freed on WINS who were playing authentic, black R&B music. He developed a love of Rhythm and Blues, especially the vocal harmony groups. After he married Diane and they started raising a family, the music scene began to change and he drifted away from the music he loved until he met a kindred spirit in Bill Olb.

Olb and Ronnie I shared a love of vocal group harmony, and he was with Ronnie when he purchased Clifton Music. Olb also helped Ronnie launch what would become a 23-year radio career. “In 1974, Ronnie was a guest on a radio show,” Olb recalled. “The following year, he took over the show, now called Ronnie I Just For You, on WHBI out of Newark NJ. When he started doing the show, he came to my house where I had some equipment and we would tape the shows on reel-to-reel.”

Tony Oetjen discovered Ronnie I through his uncle who told him about the radio show. “I would listen to Ronnie’s show every Sunday night when I had school the next day and was supposed to be in bed. My mother and father would come in and say “Turn that thing off and get to sleep!”

“I was born in the Bronx and transplanted upstate to the Hudson Valley area by the time I was in high school," Tony said. “I was always interested in the music because my father sang in a group called the Crystal Chords in the 50s. He wasn’t on any records, but he recorded some demos with another group called the Crimsons. It was his claim to fame.”

"Before we moved upstate, my father would put the radio in the window, and he and my mother would sit outside on lawn chairs on warm nights and listen to Gus Gossert’s show,” Tony recalled. “It became a ritual. Every Saturday night my father would take out the records and my brother and I would play them and he would listen. It was around 1974. I was ten years-old at the time.”  Tony "Tony O" Oetjen

Tony "Tony O" Oetjen

“I never thought I would ever meet Ronnie but, after I enrolled in Rockland County Community College, I got involved in the college radio station and it kind of engulfed my life”, Tony said. “One of the girls at the station, who did a jazz show, asked if I knew Ronnie because I played my doo wop records and some of my father’s records on the air. She asked if I wanted to meet him. Her sister was dating one of the guys in the group Charm, who Ronnie had recorded, and she brought me to a UGHA show.”

“A couple of weeks later, I decided that I wanted to go see Clifton Music. I drove my car there, and I was overwhelmed by the rare records hanging on the wall that I had heard on the radio but only dreamed about owning,” Tony recalled. “I’m in there, maybe 5 minutes, and I walked up to counter and introduced myself to Ronnie who immediately asked me to watch over the store for 15 minutes while he went to the post office. Over an hour later, Ronnie returned to the store, and we became very good friends soon after.”

“From that point on, I helped around the store whenever I could and also helped at UGHA events - just doing the stuff that he needed help with," Tony said. “I also worked on his radio shows. I helped him get on WNYE. It was originally supposed to be my show, but I wasn’t ready and I passed it over to Ronnie. He stayed on the station from the mid-80s until 1998. Medgar Evers College in Brooklyn shared broadcast space with the City of New York and the New York Board of Education, and Ronnie used the studio at Medgar Evers for his show.”

By the early 1980s, Ronnie already had a lot of irons in the fire with the store, the UGHA, the Lymon tombstone, the shows, and now record production. “My dad’s passions were his family, the music and the New York Yankees” Ron Italiano Jr explained. “His work with the UGHA didn’t exactly cause a rift, but my parents just gradually grew apart. They wanted different things.”

Bill Olb, a longtime friend of both Ronnie and Diane, had a slightly different take. “I believe the divorce was around 1983 or ‘84. They were wonderful people, and Diane was always very good to me because I knew Ronnie before there was ever a UGHA,” Olb recalled. “I believe the cause was after Ronnie started the UGHA he began to work on recording vocal groups in the evening. Diane was wasn’t receiving any attention. She was by herself very much of the time. I wouldn’t say it was the UGHA in itself, but it was the UGHA and his activities. He was involved in doing so many things that he was not home maybe five nights a week.”

In 1987 Ronnie was profiled by Pacific Street Films, a documentary film company founded in 1969. The company had done a documentary in 1983 called I Promise To Remember: Frankie Lymon & The Teenagers. The feature on Ronnie was shot by Joe Sucher who was hired by WNYC, the station that carried Ronnie’s radio show at the time.

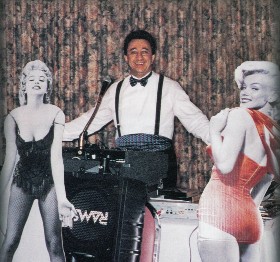

“We are into the authentic music. A lot of people through the years have put out this music as a parody,” Ronnie explained in the film. “I mean Sha Na Na, I’m not taking away from their talent but that’s not the 50s. The 50s and the music is not slicking your hair back, putting your collar up, and going ‘wah-wah-wah.’ It’s an art form, and we bring out that art form at UGHA.”  Ronnie at a UGHA show

Ronnie at a UGHA show

“People come to the shows because they want to keep this music alive. They’re here to enjoy big name groups, like the Paragons, or the local acapella group who maybe work in a factory or a drug store and once a month they are able to come out, after practicing all month, and display their talents on a stage for people who really enjoy it.”

“I grew up in the 50’s. I was into black music but I was raised in a white, middle class area,” he said. “I married at a young age, had three children, and I was driving a beverage truck. In January of 1972, I took a big gamble in life, bought Clifton Music and slowly turned it into the world’s # 1 doo wop shop.”

“I’m very happy, and I’m very confident in 1987, and I think that the music is here to stay,” Ronnie said. “We’ll call it doo wop, we’ll call it oldies, we’ll call it group harmony, whatever you choose. I think the American art form of music with a lead singer, a first tenor, a second tenor, a baritone, a bass, and a blend of harmony is here to stay.”

Christine Vitale was born in New Jersey and graduated from high school in 1983. She got into older music first through the recordings of Elvis Presley and then into the roots of where he was getting his material from. As a result, she became more curious about the vocal groups that Elvis covered on his early recordings.  Christine Vitale

Christine Vitale

She first learned about the UGHA through a brochure she picked up while attending another event. “It was relatively inexpensive to join,” Christine recalled. “I tried it thinking that it would broaden my scope of music, and it did.”

“I met Ronnie in 1988 through the UGHA and, by the end of 1989, I began working with him. I started helping Ronnie on the radio shows, and he eventually incorporated me as a co-host. The show was on Medgar Evers Radio at the college. The program was more of a historical show that highlighted certain aspects of the music and its history,” Christine said. “Ronnie saw the show as a way to promote his business and his UGHA organization.”

Pam Nardella also met Ronnie in 1988 when she joined the UGHA. “I was born in Norfolk, Virginia. My mother is from the South. My father was a military guy, and my parents met when he was stationed in Norfolk,” Pam said. “My father served in the Korean War and was a P.O.W. for three years. He was from Paterson, and when he came home the family moved to New Jersey where my father bought a house in Fair Lawn. That was where I grew up and graduated in 1965.”

“I was a vocal group music fan and record collector since I was 10 years-old. I first learned of Ronnie Italiano on the radio. After my divorce in 1988, I started going to the UGHA shows that Ronnie put on in Clifton at a restaurant called Bumstead’s, located on Harding Avenue, one block from his music store. He would present acapella groups and a DJ for the entertainment,” Pam recalled. “It was a great place to hang out and meet people and dance. It was a lot of fun. We went there every Friday and Saturday night. I lived for the weekends. I think I went to every monthly show that he had, except for maybe one, from 1988 until 2008. I saw a lot of groups. I have a lot of pictures and a lot of memories.”

“There was a circuit that contained between 30 and 50 acapella groups that he could book through Ronnie I Productions,” Christine Vitale recalled. “The scene was thriving and it was good for the groups, the UGHA, Ronnie I’s business, and it kept the music out there.”

“Ronnie was my mentor when I became a DJ,” Pam Nardella said. “They had DJs playing our music in between the acapella sets, and I said to Ronnie ‘I could play better music than what these guys are doing. What do you think?’ He was okay with it, so we went and bought the equipment, and he came to my house a couple of times and taught me how to cue records.”  Pam Nardella

Pam Nardella

“I needed to get a snazzy name so we went through a few possibilities and then came across ‘Dream Girl’ by Norman Fox and the Rob Roys. I love that song, and it became both my stage name and my theme song as the Dreamgirl DJ. I got a Dreamgirl pink satin jacket and worked at Bumstead’s for a number of years,” Pam said. “I also worked with the Dubs a few times at their appearances. Later on I went on internet radio and had my own show, Doo Wop Café, on Wednesday nights from 8:00 to 9:00 PM.”

After the Frankie Lymon tombstone was installed on a riser in the front window of Ronnie I’s Clifton Music store, the stone started to attract media attention. The city of Passaic is located about four miles from Clifton. The Herald News was the Passaic newspaper, and Ronnie was asked to do an interview about the headstone. Tom Sullivan wrote for the paper and also hosted a television show about Clifton on a local cable station. His 20-minute TV interview with Ronnie covered the history of Frankie Lymon and The Teenagers and revealed that the stone was purchased from a monument company in North Arlington in 1988. The segment drew a large viewer response, and it helped the Frankie Lymon tombstone become a New Jersey legend.

Weird N.J. began in 1989 as a newsletter about local legends, ghost stories, folklore, and other unusual places in the Garden State. It was created by Mark Moran and Mark Sceurman and, because of its popularity, it soon evolved into a semi-annual magazine. After visiting Clifton Music, the pair wrote a story for the magazine called Frankie Lymon Gets Stoned that provided additional publicity for both the store and the tombstone.

This led to Ronnie hosting groups of people who were part of the Weird New Jersey bus tours that placed the store on its itinerary of unusual places to visit. One of Christine Vitale’s jobs was to greet the groups and present the story of Frankie Lymon’s tombstone. Ron Jr. was working at the store during that time and remembered that they used to get a lot of traffic from the Weird N.J. tours. “It was usually large groups who would come in to take photos,” Ron Jr. recalled. “They were not that interested in the music; it was more about seeing the legendary tombstone.”

According to Bill Olb, Ronnie Italiano didn’t like the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland. “He did a couple of shows there with vocal groups like the Penguins and the Harptones, but he felt the HOF board was very political and not made up of music enthusiasts,” Olb recalled. “In the early days, the Hall of Fame wanted to do something with Ronnie and the UGHA to honor his achievements but Ronnie refused. He didn’t want to be associated with it.”

Tony Oetjen agreed. “He hated the Rock Hall in Cleveland,” he said. “Ronnie didn’t think they did much for vocal group harmony, and he didn’t like the way they operated it and the way they ran it. He felt there was too much of a corporate presence.”

The UGHA had been having closed elections for its own hall of fame since 1978, but by 1991, Ronnie was intrigued by the idea of an actual brick and mortar museum for an official UGHA Hall of Fame. Ronnie appeared with Joel Warshaw and Al Karseboom on the Doo Wop Shop radio show hosted by Don K. Reed in 1991 to talk about the UGHA’s first Vocal Group Hall of Fame induction ceremony to be held at the Symphony Space in New York City.

“The idea for a hall came from discussions with Joel Warshaw, Al Karseboom, Christophe Pierre, and Christine Vitale,” Ronnie explained to Reed. He went on the say that the Cadillacs, the Clovers, the Delta Rhythm Boys, the Harptones, the Heartbeats, Shep & the Limelites, the Orioles, and the Teenagers would be the first group of inductees. He also stated and that New York City would be the perfect place for a Vocal Group Hall of Fame museum and an ideal spot to display Frankie Lymon’s original tombstone.

“I was no longer working with the Teenagers, but I continued to visit Ronnie once in a while at the store," Joel Warshaw recalled. “I helped Ronnie get an attorney to make sure the paperwork for the UGHA’s non-profit status was correct. I also came up with the idea for the hall of fame but without Ronnie, nothing could have been done. He had the base to really do something and was very enthused about it, but he had a lack of interest in the details. He was a guy who would fly by the seat of his pants.”

“I only worked on the first three hall of fame events, but they had at least ten of them along with tribute ceremonies,” Warshaw said. “What I loved about the first one was that I went to all the major labels and told them what we were doing and they were very receptive. I was up to Arista, and I met with Ahmet Ertegun at Atlantic. For me, it was like fun. I had a little argument with Ronnie at the time. I said if I go up to these majors, it’s going to help if we give complimentary tickets and hand out awards.”  Phil Groia's book

Phil Groia's book

Warshaw prevailed as evidenced by the first annual UGHA Hall of Fame event. In addition to the vocal groups being inducted, Ahmet Ertegun was honored as one of the early advocates of R&B and jazz, and Phil Groia was also honored for his landmark book, They All Sang On The Corner, a definitive history of the African-American doo wop groups of the 1950s.

“One of Ronnie’s big ideas was to have a hall of fame museum and put the headstone there,” Bill Olb said. “I was a financial officer in a bank, but Ronnie had no idea about endowments or anything like that. He had lots of ideas. Another one involved a restaurant that was going to be the home of the UGHA. Ronnie was an idea man, and they would change quickly, sometimes from week to week. Most of the time they were possibilities, but they didn’t contain a lot of deep thought, review, or research.”

“Ronnie had some potential backers who had a high net worth and had offered to fund the museum if he could find a good space for it,” Christine Vitale remembered. “Finding a good space, however, was very difficult. It had to be accessible and in a part of town that people would want to visit. Ronnie looked around New York City but everything was more expensive than even the funds would allow for. He then started looking for a space in New Jersey, but he eventually scrapped the idea. One of the problems was that Ronnie was so overworked and spread so thin that he couldn’t really concentrate on that single mission.”

Even if the museum idea would have come to fruition, it would have had to attract a lot of visitors to stay solvent. Ronnie was not into mainstreaming, however. He was a purist who loved the black vocal groups as evidenced by the 84 artists that were inducted in the United In Group Harmony Hall of Fame from 1991 to 2003. Those inductees met the UGHA’s goal of preserving and exposing authentic vocal group harmony music, but would it have been enough to make the museum a destination point for fans of oldies music?

There were two interracial groups, the Crests and the Dell Vikings, but there were no all-white vocal groups inducted. The Chantels represented the only female vocal group in the UGHA HOF although there were some, including the Kodaks, the Platters, and the Mellows, who had female singers. Most female groups did not have the all-important bass singer; but the majority had been influenced by doo wop and many were major hitmakers in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Ronnie remarried in 1995. His second wife was the former Sandi Burgos. They wed when he was 56 and she was 24. Although she was much younger than Ronnie, Sandi started listening to 1950’s vocal groups as a teenager in the 1980s. She became an avid fan and began collecting 45s and albums, including two on the Rhino label entitled “Doo Wop Ballads” and “Doo Wop Uptempo”. Each album contained a notice to contact United In Group Harmony in Clifton, NJ, “For further information on vocal group sounds.” Sandi sent for the information, joined the UGHA, met Ronnie at one of the events, and they soon became a couple.  Sandi and Ronnie

Sandi and Ronnie

According to Pam Nardella, the official wedding was June 23, 1995 at a small chapel in Clifton, NJ, with Ronnie and Sandi’s families and close friends in attendance. On June 24, a second ceremony was held for 500-700 members of the UGHA community at Scheutzen Park and officiated by ordained minister Fred Barksdale of the Solitaires.

“I was pretty close to Ronnie,” Pam Nardella revealed. “When he married Sandi, he came to the house for some dance lessons. He had no rhythm, and I taught him some steps so that he could dance at his wedding.”

“She was great for my dad even though she was the same age as his daughter Doreen,” Ron Jr. stated. “Sandi was an old soul, however, and she fit him so well.”

Ronnie I’s 23-year career on the airwaves came to an end in early August of 1998. “Ronnie stopped doing his radio show because the station wanted to cut his time to 1 hour,” Tony Oetjen remembered. “He had a 2-hour show from 9 to 11 on Wednesday nights. WNYE wanted to cut him down to 9 to 10. He wasn’t happy about that.”

“His wife was very supportive of what he did, but she wanted him to spend more time at home,” Oetjen said. “The main reason, however, was that the station wanted to sell the time to a syndicated show that would pay more money for the air time. WNYE belonged to the New York Board of Education, but they brokered time at night like the other stations around New York City.”

“That was one of the reasons he was on the station. The money wasn’t that much when Ronnie started, and he underwrote his own show through Clifton Music and the UGHA. It wasn’t a sponsored show since it was a non-commercial station, so he wasn’t allowed to have advertising. He could talk about UGHA shows and other events, however, as long as no prices were mentioned.”

“Ronnie was live every Wednesday night; he rarely missed a show. We would drive into the city, then drive back, and didn’t get home until late at night,” Oetjen recalled. “He had so many other things going on and when they wanted to cut his time, he didn’t see that it was worth it to drive into the city to just do one hour. He didn’t want to prerecord it because live listener call-ins were an important component of his show.”  Why Do Fools Fall In Love poster

Why Do Fools Fall In Love poster

Just weeks after the radio show ended, Hollywood entered the picture with the Why Do Fools Fall In Love movie. Frankie Lymon’s story was a film script waiting to happen, and Rhino Films and Warner Bros. (the people who now owned the music of Frankie and the Teenagers) made it into a major motion picture that was released nationally on August 28, 1998.

The film starred 24-year-old Larenz Tate as Lymon. Although he gave an energetic performance, realism was tossed out the window when he had to portray the 13-year-old Frankie breaking into the big time with the Teenagers early in the film.

Wisely, the movie spent most of its time recounting the relationships that rock and roll’s first teenage star had later in his career with the three women he married. This was done through a series of often humorous flashbacks during the courtroom testimony of the three wives (Halle Berry as Zola Taylor, Vivica A. Fox as Elizabeth Waters, and Lela Rochon as Emira Eagle) who claimed to have legally married Lymon and were vying to be named the rightful heir to his songwriting royalties to “Why Do Fools Fall In Love.”

The film failed to mention, however, that Frankie Lymon had been buried in an unmarked grave for two decades. In doing so, it missed the chance to include the fascinating side story of Ronnie I and the UGHA’s efforts to put a tombstone on his grave and how they were rebuffed by Emira and her legal advisors’ quest for the big payday.

“Ronnie was indifferent to the movie,” Christine Vitale recalled. “When people did something that touched on his area but didn’t contact him or respect what he had done, he felt marginalized. No one with the film called on him, and he felt that his efforts were not given proper credit. Credit would have helped the UGHA, Ronnie I Productions, and Clifton Music. He took it very personally.”  Life Could Be A Dream DVD

Life Could Be A Dream DVD

Although it was not a glossy Hollywood production, Ronnie and the music he loved were celebrated in a 2002 Canadian documentary called Life Could Be A Dream: The Doo Wop Sound. The film was a history of the group harmony genre and included the story of Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers.

The documentary also contained vintage vocal group performance clips along with interview footage with numerous artists considered doo wop royalty: Jimmy Merchant of the Teenagers, Lewis Lymon of the Teenchords, Earl “Speedo” Caroll of the Cadillacs, Arlene Smith of the Chantels, Pookie Hudson of the Spaniels, and Dave Sommerville of the Diamonds.

Cyndy and the Cliftonaires and Things To Come, two contemporary vocal harmony groups that Ronnie produced for his own Clifton label, performed in the documentary, and Ronnie was interviewed at Clifton Music wearing his New York Yankees’ attire. It was the perfect setting and subject matter, but it would also turn out to be Ronnie's final filmed appearance before he became seriously ill.