Ronnie Italiano, one of the true champions of vocal group harmony music, died of liver cancer at the age of 67 on March 4, 2008. The family received visitors at the Macagna Diffily Funeral Home in Rutherford, NJ on Friday, March 7th. The next morning there was a funeral mass at St Josephs R.C. Church in East Rutherford. It was followed by Ronnie’s internment at St. Joseph's Cemetery in Lyndhurst. It was a very difficult time for his family, his friends, the membership of the UGHA, and the many vocal groups he supported over the years.

“My dad discovered he had cancer three years or so before his death,” Ron Italiano Jr. said. “He had a small stroke years before and heart problems ran in the family. His brother had a heart attack, and his father died at a very young age. Dad had heart issues, but it was cancer that finally got him.”

“Our family had stayed together over the years following the divorce. It was hard at first, but my mom and dad wanted the same things for their kids so they got along – especially when grandkids started to come along. Mom remarried as did Ronnie, both to great spouses. Mom visited dad in the hospital before he died, so they ended on a good note.”

“I don’t remember how long Ronnie lasted, maybe a year or two,” Pam Nardella recalled. “He used to come to the UGHA meetings, but he lost weight and he lost his hair. I went to see him when he was on his death bed, and I was able to say good-bye. It was tough.”

“He underwent chemo, his hair fell out, and he was wearing a toupee at the end and being wheeled around in a wheelchair,” Tony Oetjen said. “Nobody had a greater impact on vocal group music than Ronnie I. His importance is still being felt today. None of the groups that are still around today would be here if it weren’t for Ronnie.”  Ronnie and Sandi Italiano

Ronnie and Sandi Italiano

Ronnie’s passing brought the UGHA to an end. “The last newsletter, sent out by his widow Sandi, stated that it was his wish to not to continue the UGHA," recalled Joel Warshaw. “To a huge degree, it would have been difficult to keep it going without Ronnie, but generally when a person develops something as nice as that, they want their legacy to carry on.”

“Ronnie’s final newsletter indicated that he wanted the UGHA to end with his passing,” Pam Nardella said. “The members were sad. Some people felt that it should keep going, but most wanted to abide by his wishes. It would have been very difficult for someone to step up to the plate and be like Ronnie.”

“Ronnie gave his wife Sandi the option of keeping it going if she chose to, but she didn’t want to,” Tony Oetjen remembered. “It was a lot of work, and Ronnie was really the only one who knew exactly what to do with all of it. The UGHA was the greatest thing ever. There were a lot of people disappointed that it came to an end. Ronnie passed away just days after attending the last UGHA meeting and show. I still have my UGHA membership card, and I keep it in the area where I record my radio shows.”

“My dad was the kind of guy who felt he was the only one that could do it right,” Ron Jr. said. “The UGHA was his baby and no one was going to tell him how to run it. He was the only one who would who would fight and give up everything for it. He felt that no one could fill his shoes, that no one would sacrifice what he did for the music.”

“UGHA had to close because there was no one left who could run it like Ronnie," Bill Olb stated. “He went at it 24-7. Ronnie managed some of the groups and got them work, but he didn’t take any pay for his services. There were so many unbelievable things that he did for groups and people. He would go over budget if groups wanted more and pay them out of pocket. He was very special and very dedicated to vocal group music.”

I met Ronnie a couple of years prior to his death by pure happenstance. Our son Brennan and his wife JoJo purchased a house in Roselle, New Jersey, in 2003. They had lived in an apartment in Astoria, Queens, since arriving in New York in 1995. They both found jobs in New York City and experienced the horror of 9-11 firsthand in 2001. The move to New Jersey came about after they decided to start a family.

My wife and I had visited them many times while they were living in Astoria, but we had never been to New Jersey until they bought the house in Roselle. It was very different from New York where we traveled from place to place via the subway system. We often flew to New York from Michigan because we didn’t need a car to move about, and finding a place to park it overnight was always an issue.

Life in Roselle was similar to that at our home in Michigan, only a lot more crowded. Having a vehicle was a necessity to get around, so we always drove to New Jersey. While Brennan and JoJo worked during the week, Lynn and I gradually became a little more confident about driving around the area.  Weird N.J. book jacket

Weird N.J. book jacket

It was on one of these outings that we stopped at a Barnes & Noble in the nearby city of Clark. While perusing the aisles, a book entitled Weird N.J. (Your Travel Guide to New Jersey’s Local Legends and Best Kept Secrets) piqued my interest. I bought it thinking it would be a fun little housewarming gift for our son and his wife, but it turned out to be something more.

As the title suggests, the book lists all the odd, mysterious, and offbeat spots that you can visit in the Garden State. It was fun leafing through it, but something on page 240 really caught my eye. Listed under a chapter titled Cemetery Safari was a segment called “In Clifton They Remember Frankie Lymon”. It briefly recounted the story of record shop owner Ronnie Italiano and how he happened to have the tombstone of 50’s teen rock and roll star Frankie Lymon displayed in the front window of his Clifton Music Store.

I had been a long-time fan of Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, but I was only 9-years-old when they released “Why Do Fools Fall In Love” and their other early hits. I hadn’t yet started buying records at that time, but I had collected most of the group’s songs in one format or another in the years since. I knew much of Frankie’s history and that of the group; and we had met Herman Santiago, along with Bobby Jay and Timothy Wilson, in 2005 when the Teenagers appeared at the Rockin' 50's Fest II at the Oneida Casino in Green Bay, Wisconsin. Lynn and I also saw the Why Do Fools Fall In Love movie when it was released in 1998, but I knew nothing about the tombstone episode until I purchased the book.  Autographed CD from Green Bay

Autographed CD from Green Bay

In Weird N.J., Ronnie was quoted as saying, “Sometimes people will come in to the shop and ask me if I’m a stonecutter and if I can carve a tombstone for them. No, I tell them, I’m just a fan.” Ronnie Italiano sounded to me like a pretty interesting guy, and since Clifton was only a 25-minute car ride from Roselle, we planned to drive over to see the tombstone and possibly meet him at his music store on our next visit to New Jersey.

Back in Jersey several months later, we motored over to Clifton while our son and daughter-in-law were working. Clifton was a city of roughly 80,000 with a tidy downtown area that showed none of the signs of urban decay. Clifton Music was located in the business district on Main Avenue, and the first thing we saw as we walked up to the shop was Frankie Lymon’s headstone in the front window on a riser surrounded by artificial flowers.

Ronnie I’s appearance was what some might expect an Italian guy from Jersey to look like. He was short, with dark hair combed back in a style that was popular in the 1950s. He wouldn’t have seemed out of place in an episode of The Sopranos in which Tony, Paulie, and Sylvio stop by the shop to pick up a couple of their favorite doo wop collections to listen to on their way to whack some wise guys. In fact, some exterior scenes for the popular HBO series were shot in Clifton.

An independently owned music store like Ronnie’s was a throwback to earlier times. It was relatively small, but he made it successful by catering to a niche that was ignored by the larger chain retailers. Ronnie claimed that Clifton Music is the largest retail outlet of vocal harmony records in the world.

Most of us called this type of music doo wop, but not Ronnie I. He disliked the term “doo wop”, which he felt both trivialized and insulted the music he loved and grew up with. He was really swimming against the tide in that respect because doo wop had become the universally accepted term for the vocal group music popular in rock and roll’s first decade. In addition, nearly all of the compilations of vocal harmony groups that he sold in his shop had “doo wop” in their titles. But in Ronnie’s defense, his interest in vocal group harmony predated the rock and roll era. More than 25% of the UGHA’s Hall of Fame honored artists who were making records long before the 1950s.

There was an impressive selection of vinyl records, CD’s, books, magazines, videos and DVDs at Clifton Music. In addition, Ronnie sold t-shirts and jackets with the UGHA logo, vocal group recordings that he produced on his own Clifton label, and DVDs of the many vocal harmony shows he put together over the years.  Lu Pine Records CD

Lu Pine Records CD

As you can probably imagine, almost everything in his shop dealt with vocal harmony groups, although I did find a nice collection of Mary Wells’ songs that she cut after leaving Motown. I also bought the “Golden Era of Doo-Wops: The Groups of Lu Pine Records” CD that highlighted one of Detroit’s independent labels. Lastly, I purchased a copy of Philip Groia’s They All Sang On The Corner, one of the earliest published books about the vocal groups of the 50s from the New York City area.

While speaking with Ronnie, I learned that most of his shows were centered on the inductions into the United In Group Harmony Association’s Hall of Fame. Started in 1991, it contained 84 inductees and almost all of the groups were formed prior to 1960. Since the Chantels were the only female vocal group listed, I asked Ronnie about one of my favorites, the Shirelles from nearby Passaic, New Jersey. He quickly dismissed them, however, stating that they lacked the vocal harmony skills to qualify for induction.

Motown artists like the Miracles, Marvin Gaye, the Supremes, the Four Tops, and the Temptations were all heavily influenced by the early doo wop groups, but no Motown acts were included. Ronnie explained that he felt that Motown was a separate thing from the vocal harmony groups that he loved. In his opinion, Motown was basically dance music, and he was disdainful of the singing ability of the label’s most successful girl group, the Supremes. The only artists from Michigan that were in the UGHA Hall of Fame were the Diablos and the Midnighters.

Ronnie and I also talked about Frankie Lymon and the movie Why Do Fools Fall In Love, the film based on Lymon’s life and the court battle that involved the three women all claiming to be his rightful heir. He didn’t care for the movie, but he was excited about the next show he was producing in Clifton featuring Earl Lewis and the Channels, and he invited us to come. I explained that we were just visiting, but I promised to check out his website and would try to catch one of his shows if we were in New Jersey at the same time.  UGHA 30th Anniversary

UGHA 30th Anniversary

If I lived in the Clifton area, I would have certainly joined Ronnie’s organization. $25 bought a one-year membership in United In Group Harmony Association. It entitled you all club benefits such as discounts on everything sold at Clifton Music. It also included discount admissions for the UGHA’s monthly meetings/shows that usually featured contemporary harmony groups, like the Infernos or the Cliftonaires, who emulated the classic sounds of the past.

The gatherings also provided an opportunity for Ronnie to track down the singers of such great groups as the Cadillacs, Heartbeats, and Five Discs and have them perform, in some cases, for the first time in decades. In a 1998 interview, Ronnie explained “What we do is keep the music alive for the people who love it and the people who made it. There aren’t many other places to hear it.”

It was a fun afternoon both talking to him and checking out Clifton Music, but I also discovered that Ronnie was battling cancer at the time of our visit. I found this out by accident because Lynn and I were the only other people in the shop, and I happened to overhear a phone conversation during which Ronnie described some of the tests that were run on him the previous day.

After we got back to Michigan, I looked up Ronnie Italiano’s name on the Internet and found out some more interesting information about him. On the New York Times website there were several stories about his rock and roll exploits. One involved Joe Frazier, not the fighter but the black lead singer of an interracial group called the Impalas who had a big hit in 1959 with “Sorry (I Ran All The Way Home)." Frazier had lost both of his legs to diabetes, and Ronnie had hosted a benefit for him featuring the Duprees, the Dell Vikings, and the Cadillacs.  Joe Frazier (left) with the Impalas

Joe Frazier (left) with the Impalas

Then there was the story of Gerald ‘Bounce’ Gregory who had performed with the Spaniels for over 45 years. Gregory had sung the “dip-du-dup-dup-dum” riff at the start of the group’s classic recording of “Goodnight Sweetheart Goodnight," but he was buried in an unmarked grave. Ronnie and the UGHA raised $3,000 for an engraved tombstone for his resting place.

Another dealt with lead singer Harry Douglass of the Deep River Boys, one of the four or five groups that defined the black vocal quartet style of the 1930s and 40s. Because of the UGHA, Douglass’ career was revived, and he was able to share his music and his history with a whole new audience.

All these things came at a price, however. Keeping Ronnie's dream alive resulted in a thirty-year struggle to subsidize the UGHA. Travel and production costs for his shows ran into thousands of dollars, which had to be recouped through admissions, raffles, dues, donations, souvenirs, vendor fees, and sales of videotapes and DVD’s. If these things couldn’t cover the costs, Ronnie would go into his own pocket.

“The UGHA was a non-profit organization, and Ronnie put a lot of his own money into it to keep it going," Bill Olb revealed. “No one would do that - put in $30,000 or $35,000 a year to keep it running, and no one in the organization knew he was bankrolling it with his personal funds and putting some on credit. When Ronnie passed there was a great deal of problems that I had to handle. These included debts that were eventually settled, and I put in some money to help settle them. Ronnie didn’t handle money the way you would like it to be handled. The store had debts as well as the UGHA. Ronnie ran shows, but didn’t charge enough money to cover paying for the acts and then covered the losses on credit cards. Sandi had no clue as to what was going on, but I had a lot of experience in that area. I worked with an attorney to resolve all of the estate issues.”

I hadn’t seen or talked to Ronnie since our first meeting. Early in the summer of 2008, we were planning a trip to New Jersey, and we intended to set aside a day to drive down the Garden State Parkway and visit Ronnie at his Clifton Music Store. Unfortunately, we didn’t get the opportunity. While going on Clifton Music’s web site to check the store hours, I saw the memorial notice that Ronnie had died in March from liver cancer.

I’m not sure why I felt so bad reading of Ronnie’s death. I didn’t get to know him well, and Lynn and I only met him by chance after we traveled to Clifton to take a look at the Frankie Lymon tombstone. While reading more about him, however, I learned that Ronnie Italiano took the vocal group harmony that he loved and he found a way to make it his life. In the process, he also helped make the world a little better place to live for the people who made that music and for those who shared his love of it - a pretty good example of a life well-lived.

Sadly, Clifton Music lasted just five more years after Ronnie’s passing. Following his death, the store was run by his widow Sandi until finally closing its doors forever on March 23, 2012. “His widow tried to keep it going, but she hadn’t really been that involved while Ronnie was alive,” Christine Vitale recalled. “Sandi was overwhelmed and didn’t really know how to service the market that she had so little to do with in the first place.”

Ronnie’s old friend Bill Olb was with him when he bought his store on January 22, 1972, and he was at the store the last day it was open. Olb basically ran the store for five years after Ronnie passed. “I did all the ordering because Sandi wasn’t really interested in working in the store,” Old said. “I had my bank job, but on Saturdays I would work all day at Clifton Music. It was busy with people who came to the store and wanted to talk to someone who knew the music, including collectors and enthusiasts.”  Removing the tombstone from Clifton Music

Removing the tombstone from Clifton Music

The tombstone stayed in the store until early 2012. By then, it was clear that it was time to sell the building and get out of the business. “When Sandi decided to sell the real estate containing the store, she contacted the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame about the Frankie Lymon tombstone but there was no interest,” Olb stated. “She also tried the Smithsonian in Washington D.C., but the people in charge had no knowledge of the Teenagers or any of the other early vocal harmony groups.”

After Sandi Italiano asked if she would take it, Pam Nardella organized the move of the tombstone to her yard in Elmwood Park. “I told her that it was too heavy to bring into my house, so I said I would put it in my garden," Pam recalled. "In February of 2012, I had a friend of mine make a cement base for the stone, and then I called Paterson Monument to transport it. I didn’t want to see it go to a rock pile. The fans donated $3,000 to have the tombstone made. It was very emotional to move it from Clifton because it had been there a long time. I paid for the move myself, but I did have some musical friends who contributed and made donations. Paterson Monument only charged me $250 for the move, and the fellas that moved it were very compassionate.” Pam Nardella's garden

Pam Nardella's garden

A couple of Pam’s neighbors were concerned when the tombstone was placed in her yard. “They thought I had either buried my dog or that there was a person there. They called the building department at Elmwood Park, but fortunately I knew the building inspector,” Pam said. “I told them that it was just a piece of history, and I showed them the article in Weird N.J. Once I explained it, everything was fine and one of them even came to my first ceremonial barbeque.”

“One hundred people from the UGHA came to the first barbeque that summer to celebrate the tombstone. There was a lot of music, but with all the food, preparation, and cooking, I was just exhausted. I continued to do it every year thereafter, but the number of people dwindled with each passing year.”

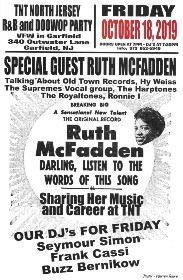

TNT Doo Wop PartyIn addition, Tony Oetjen and Tommy Harford started the TNT Doo Wop Party after the UGHA ended. “We played records every month at the local VFW,” Pam said. “It was an off-shoot of UGHA so that the people could get together. We’d meet once a month on Friday nights and have guest DJs. Ruth McFadden came to one of our meetings.”

TNT Doo Wop PartyIn addition, Tony Oetjen and Tommy Harford started the TNT Doo Wop Party after the UGHA ended. “We played records every month at the local VFW,” Pam said. “It was an off-shoot of UGHA so that the people could get together. We’d meet once a month on Friday nights and have guest DJs. Ruth McFadden came to one of our meetings.”

After Ronnie’s death, several former friends and members of the UGHA also kept his spirit alive by setting up a yearly Sunday afternoon tribute to him called “Rhode Island Island” at Lead East, the largest classic car and oldies festival in the Tri-State area of New York, Connecticut, and New Jersey. “Everyone there rented a spot, and the Rhode Island people called their spot the Rhode Island Island,” Pam said. “Tony Oetjen did the tribute to Ronnie I, and they set up turntables, speakers, and microphones; and groups came there to sing.”

Tony Oetjen and Pam Nardella at the Ronnie I Tribute at Lead EastAll of these events continued each year until they were interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Through it all, the original Frankie Lymon tombstone remained firmly planted in Pam Nardella’s garden, surrounded by irises and tulips. It seemed to all concerned that that the tombstone had found a final resting place, but it was moved once again on a sunny December afternoon in 2020.

Tony Oetjen and Pam Nardella at the Ronnie I Tribute at Lead EastAll of these events continued each year until they were interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Through it all, the original Frankie Lymon tombstone remained firmly planted in Pam Nardella’s garden, surrounded by irises and tulips. It seemed to all concerned that that the tombstone had found a final resting place, but it was moved once again on a sunny December afternoon in 2020.