The failure of their equipment to arrive in time for their first Michigan gig in the summer of 1967 led to a friendship between The Who and SRC and an offer for the Ann Arbor band to record for The Who's record label.

1967 would be important for The Who, but at the beginning of the year the band was in debt. They were pop stars in England as a result of five consecutive Top Ten singles and one Top Ten album released in 1965 and 1966, but success in the lucrative United States market had eluded them thus far. Only “I Can’t Explain” (# 93) and “My Generation” (# 74) had managed to chart on the Billboard Hot 100, and the band had yet to appear in North America.

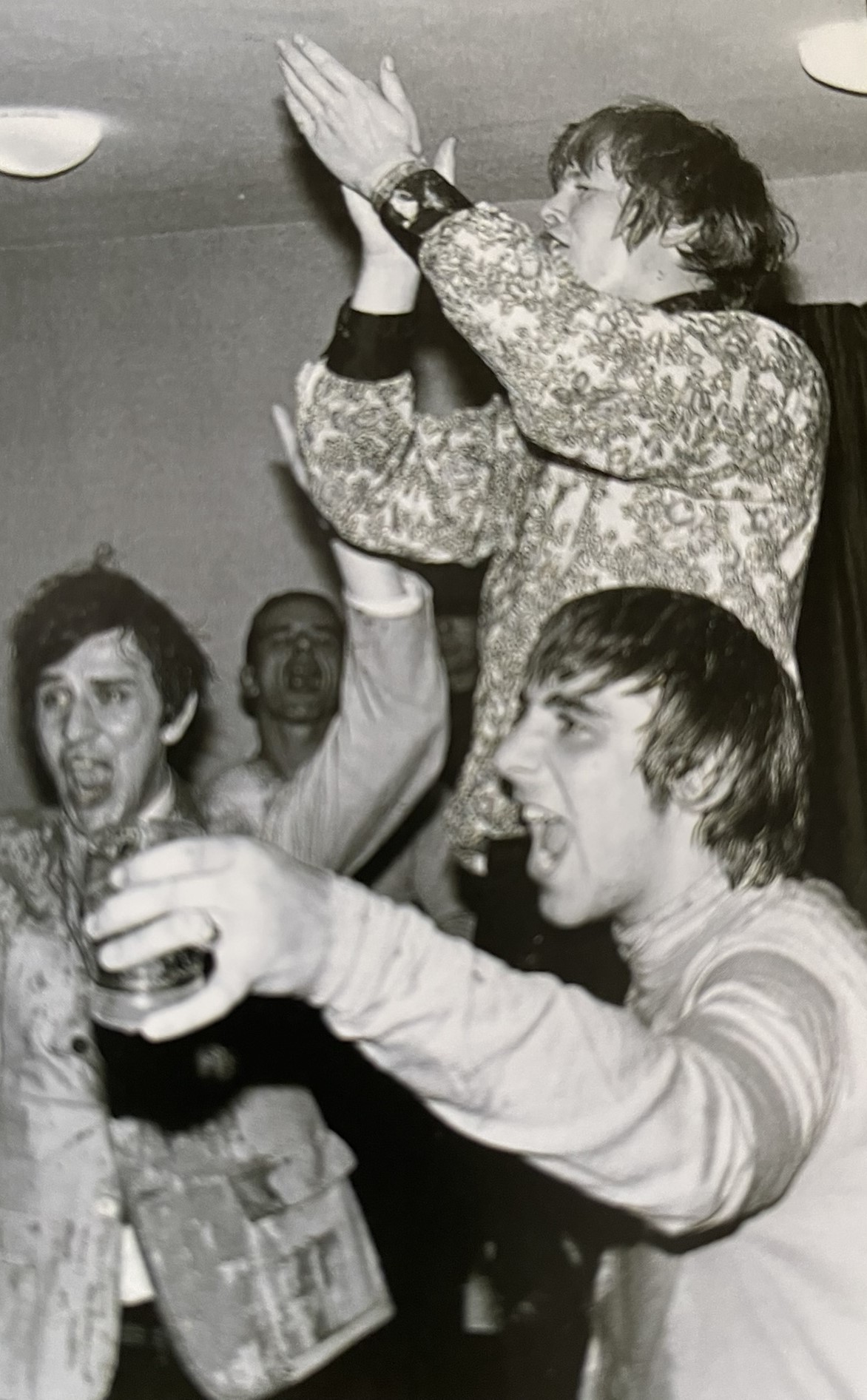

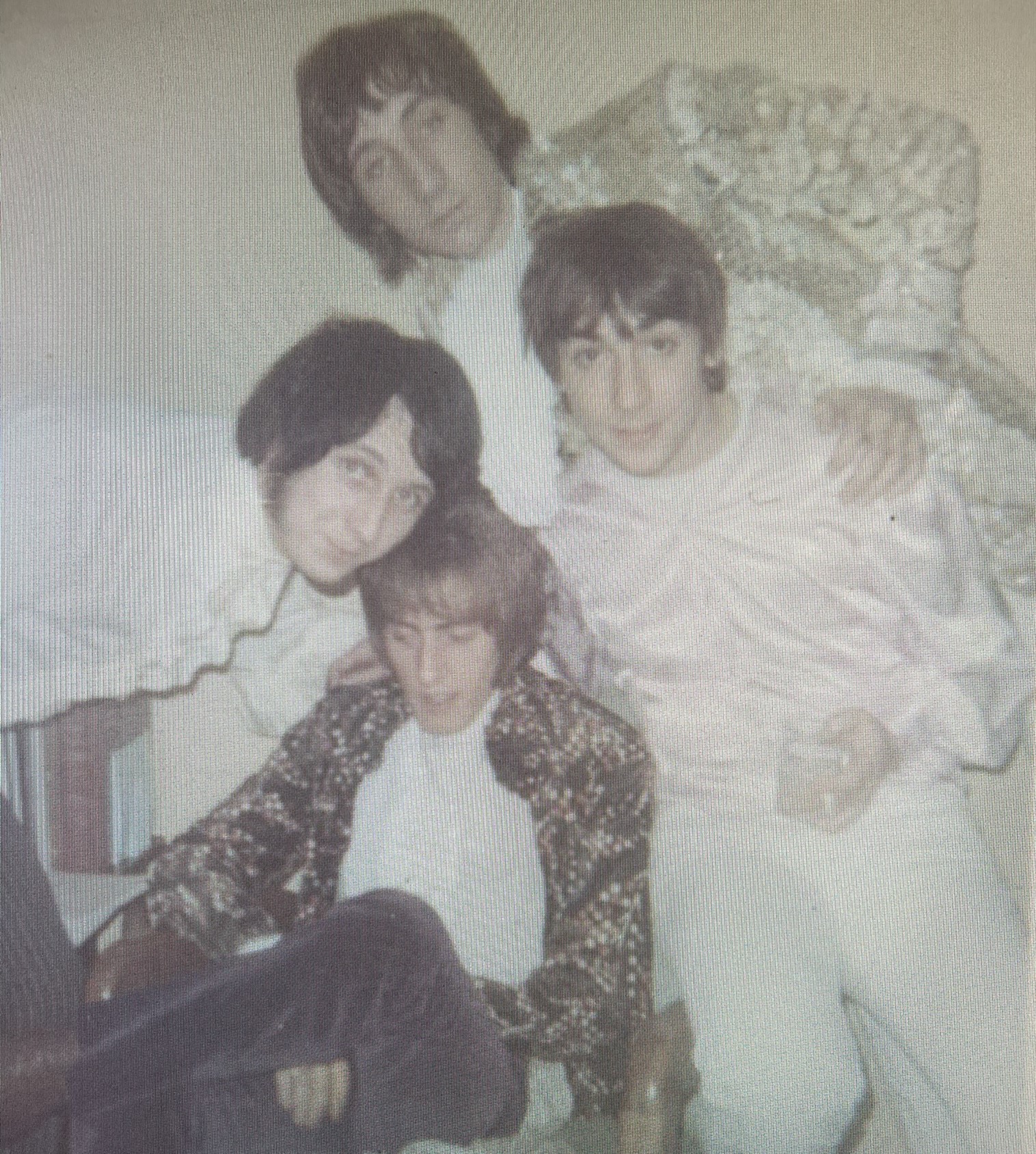

Roger Daltry, John Entwistle, Keith Moon, Pete Townshend

Roger Daltry, John Entwistle, Keith Moon, Pete Townshend

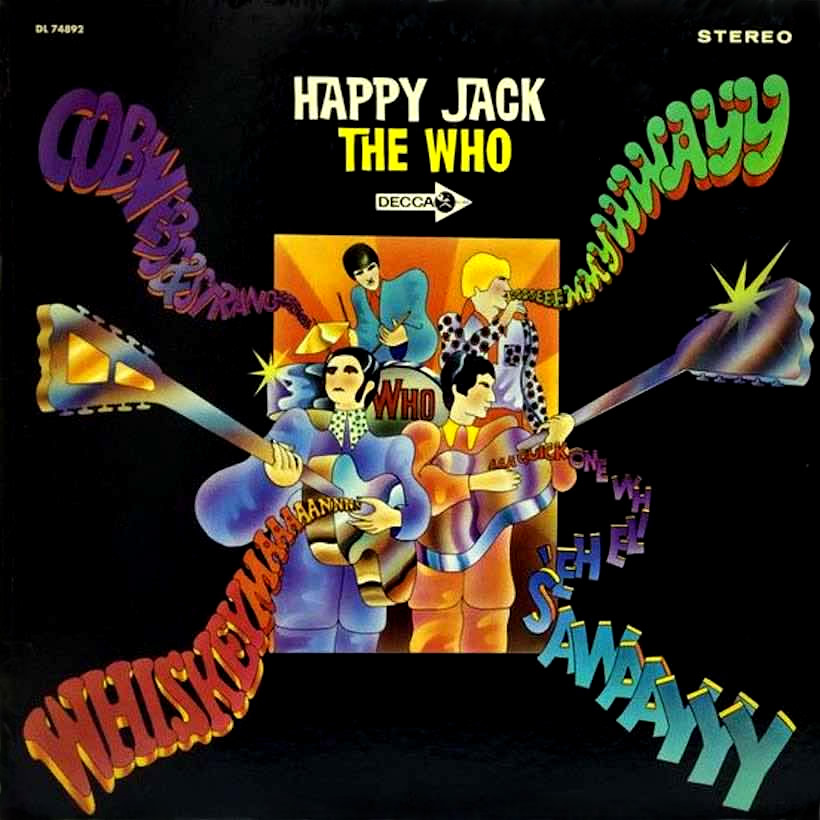

The new year saw The Who turn things around in a major way. They enjoyed their first Top 40 single in the United States, and they released their second album that contained a nine-minute suite of songs called "A Quick One, While He's Away" that was a precursor to their rock operas “Tommy” and “Quadrophenia.” The Who also launched their first tour of the United States at a teen club in Ann Arbor, Michigan, albeit with the borrowed equipment from a local band soon to be named SRC.

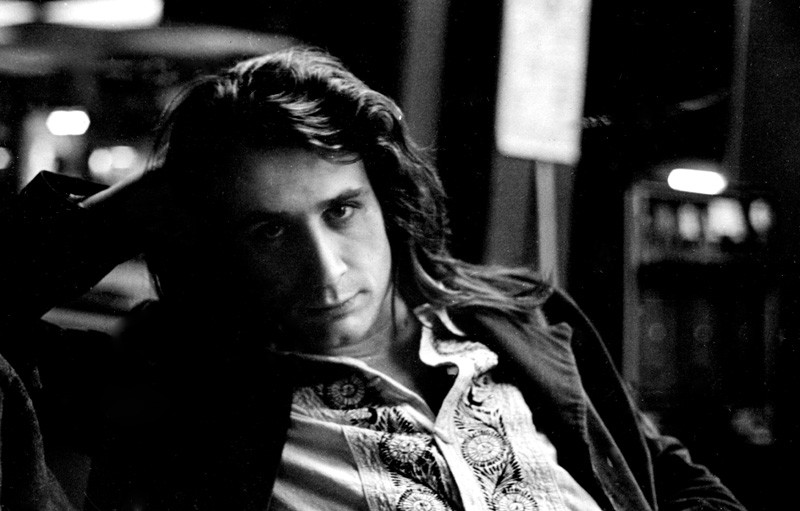

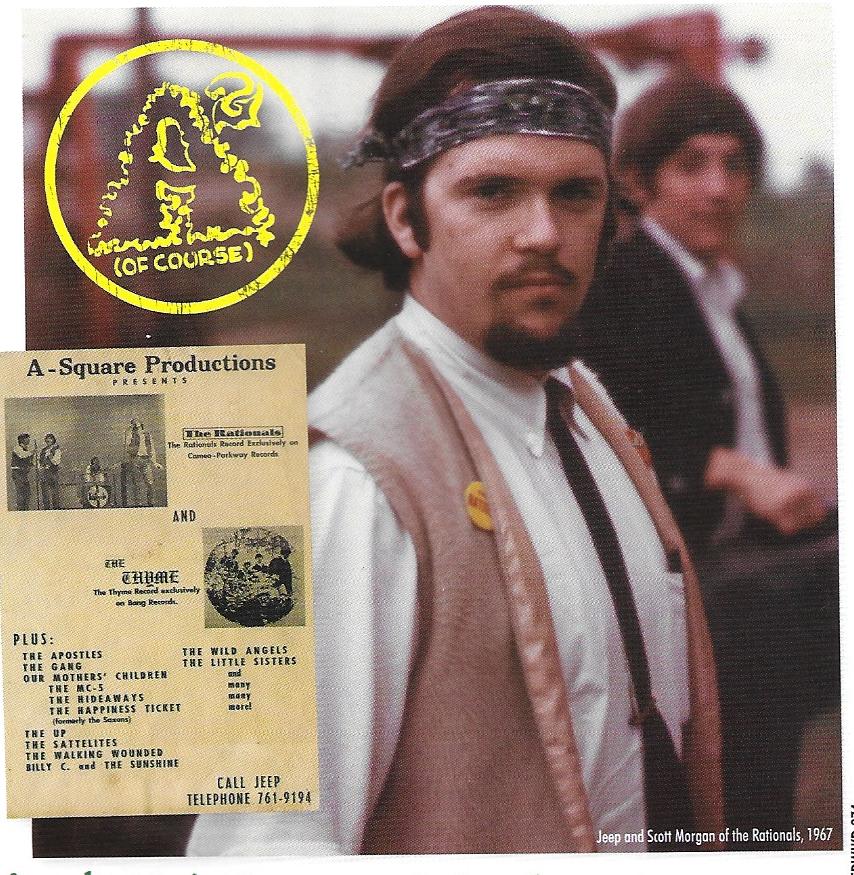

That band came together in late 1966 under the mentorship of Hugh “Jeep” Holland, the owner of local booking company called A-Square Productions and also the A-Square record label. Holland, an avid record collector, also managed the Ann Arbor branch of Discount Records. Holland had made a name for himself as the manager of The Rationals, the popular Ann Arbor band that had charted on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1966 with their cover of “Respect,” six months before Aretha Franklin’s version.

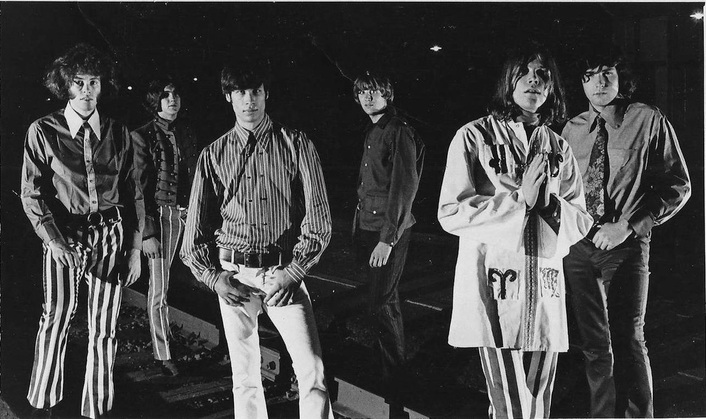

Holland started assembling the future SRC band with four members from The Fugitives: Steve Lyman on guitar, E.G. Clawson on drums, and brothers Glenn and Gary Quackenbush on keyboards and guitar respectively. Although The Fugitives had gone through a number of lineup changes, they had already recorded two singles on the small D-Town label and released an album, “The Fugitives at Dave’s Hideout,” on Dave Leone’s Hideout label.  (L-R) Robin Dale, E. G. Clawson, Scott Richardson, Glenn Quackenbush, Steve Lyman, Gary Quackenbush

(L-R) Robin Dale, E. G. Clawson, Scott Richardson, Glenn Quackenbush, Steve Lyman, Gary Quackenbush

Needing a lead singer, Holland and the Quackenbush brothers recruited Scott Richardson, the dynamic front man from The Chosen Few, a band that included future Stooges’ Ron Asheton and James Williamson. The new band’s lineup was completed when they added Robin Dale, a friend of Richardson and Holland, on bass guitar.

All of the members were fans of British rock, especially The Who. Steve Lyman recalled that he liked The Who back when he first joined The Fugitives. “The Quackenbush brothers had a copy of The Who’s first album,” Lyman recalled, “and we covered several of their early songs.”

Scott Richardson agreed. “We were all huge, really big Who fans,” he said. “I bought the first copy of ‘I Can’t Explain’ at Marty’s Records in Birmingham. I always carried it with me, and when we got the band house on Broadway Street in Ann Arbor, we were listening to their early stuff and really loving it.”

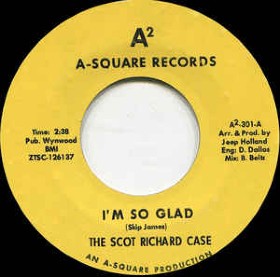

The band hadn’t yet settled on a name when Jeep Holland booked them into the United Sound Systems Studio in Detroit to record their first single in early January. “Who Is That Girl?” was an original song written by Richardson and Lyman, and the flipside was a cover of “Get The Picture” by The Pretty Things.

Because of his job at Discount Records, Holland was able to obtain a copy of Cream’s debut album that was issued in England a month before its release in the United States. The band loved Cream’s version of the Skip James’ song “I’m So Glad” and quickly made it part of their repertoire.

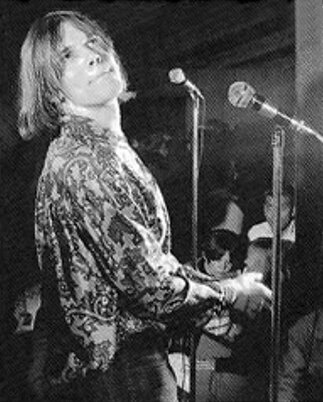

The band still did not have an official name when they played a gig hosted by Bob Dell of WTAC at the Fenton Community Center in Genesee County. The crowd reaction to “I’m So Glad” was so strong that it convinced Holland to bring the band back to United Sound Systems to record it. It replaced “Get The Picture” as the A-side of their debut single when it was released in the spring.  Steve Lyman

Steve Lyman

“It was Jeep Holland’s idea that the band be named after the lead singer,” Lyman recalled. “Scott had the idea to shorten his name to Scot Richard for his stage name, and Holland believed that a band name centered on the singer would create more attention for the group and help get our locally released record played on Detroit radio stations.”

“I changed my name to Scot Richard but I hated the idea of naming the band after me,” Richardson said. “I didn’t want to do it and everybody sort of tried to talk me into it.”

Steve Lyman remembered that they had to decide on something quickly. “Somebody in the band stumbled on my middle name (Case) as a word, and we decided the Case (or situation) about Scot Richard had an interesting ring to it.”

The Scot Richard Case quickly established itself as one of Michigan’s top bands during the next few months with impressive appearances at the Grande Ballroom, the Hideout teen clubs as well as others around the state including The Place, Crazy Horse, the Tanz Haus, the Silverbell Hideout, and Mt. Holly. There were also two events at Cobo Hall and gigs at some National Guard armories along with a variety of fraternity events on the campus of the University of Michigan.  The Fifth Dimension in Ann Arbor

The Fifth Dimension in Ann Arbor

On Saturday, March 25th, the band played at the Fifth Dimension teen club in Ann Arbor for the first time. The venue was located on the northeast corner of W. Huron and First streets. Built in the 1950s, the building originally housed the Twentieth Century Lanes bowling alley. In the mid-1960s, architect Rich Ahern acquired the property and redesigned its interior with hippie splendor. Scott Richardson remembered the Fifth Dimension fondly. “They rechristened it the Fifth Dimension because of The Byrds’ album that had just come in the summer of 1966 when all of that stuff was very fashionable.”

The cutting-edge teen club opened in October 1966, and Frank Uhle on the Ann Arbor Chronicle website described the venue as “a psychedelic showplace with trippy pulsating lights, a huge spinning Op-art wheel at the entrance, splatter-painted wall panels, carpeted sitting mounds, a sunken soda bar, and a mod clothing store.” In addition, Ahern converted the lane’s former pro shop into a dressing room directly behind a small stage that was so low that fans could stand within arm’s reach of the performers. Eight months after its opening, the Fifth Dimension would be where The Who would meet the Scot Richard Case.

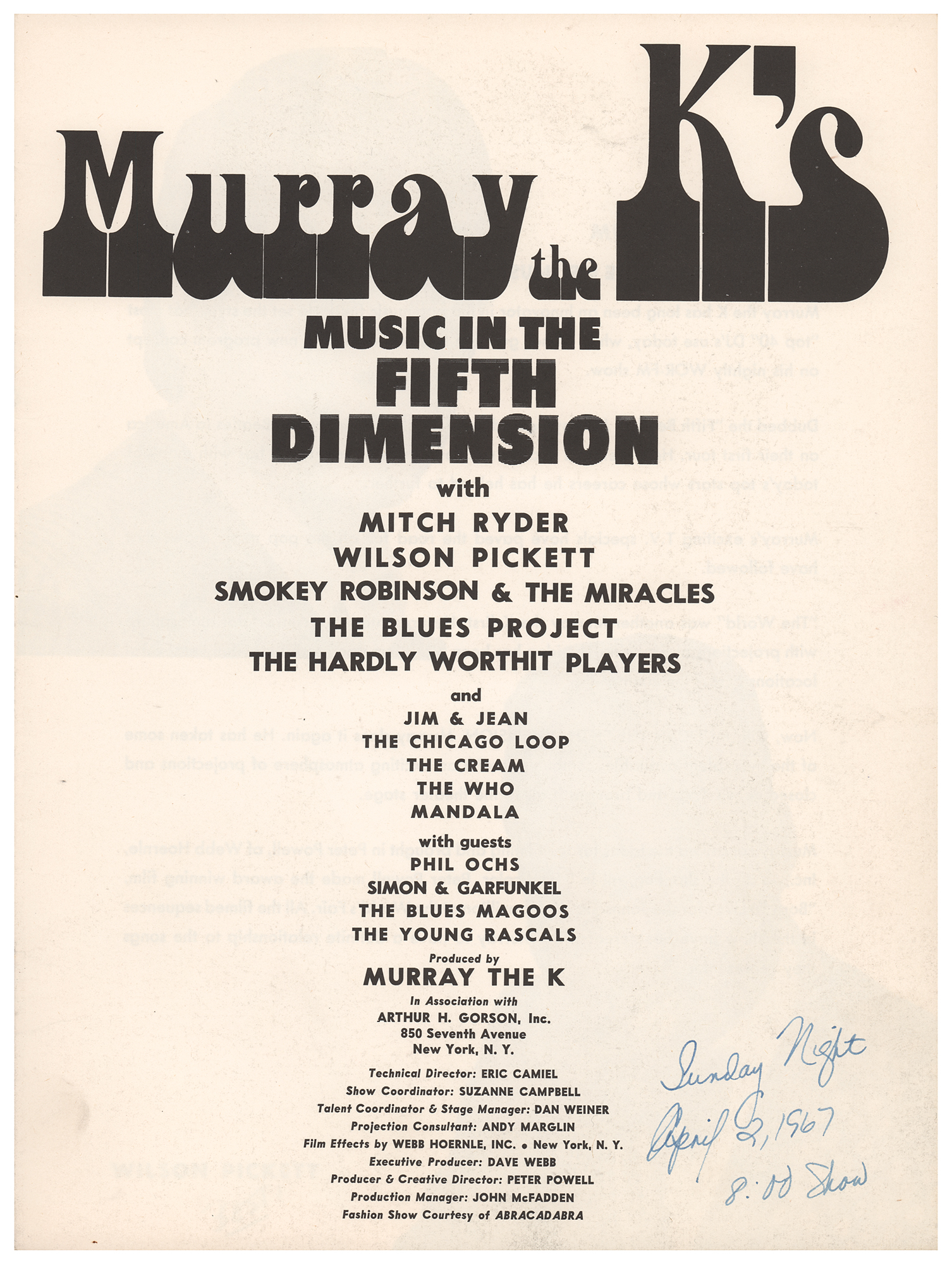

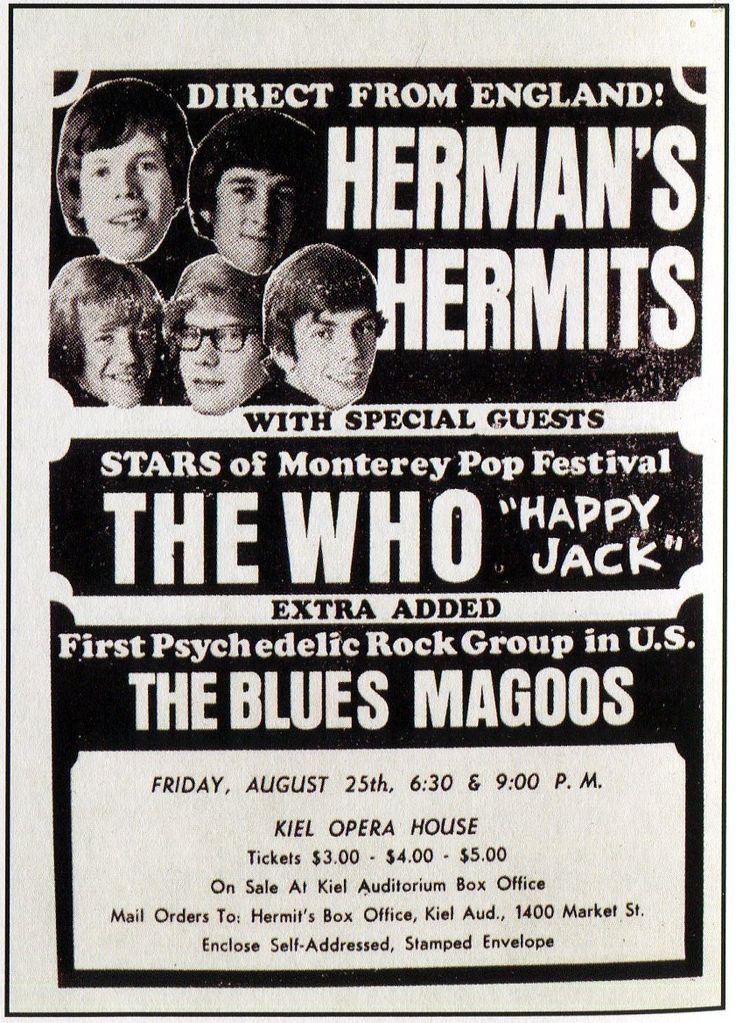

In December of 1966, The Who released their latest single, “Happy Jack,” in England, and it soon became the band’s sixth Top Ten hit there. Hoping to finally break the band in America, Decca Records planned to mount a publicity campaign in advance of the record’s release. It would be in coordination with The Who’s first U.S. appearance as part of a package show run by New York DJ Murray the K, titled Music in the Fifth Dimension.

Set to start March 25, 1967, and run for nine days at Manhattan’s RKO 58th Street Theater, the event was headlined by Mitch Ryder and also featured Wilson Pickett, the Blues Project (with Al Kooper), and Cream who was also making its U.S. debut. In addition, the special guests that appeared on certain dates included Simon & Garfunkel, the Blues Magoos, the Young Rascals, and Phil Ochs.

Not only did the concert have to find time for all of these acts, the whole performance took place five times a day, every day – from 10 a.m. until past midnight. As a result, both Cream and The Who were allotted only 12 minutes to deliver their tunes at each performance. “We were smashing our instruments up five times a day,” Townshend recalled in Musician magazine.

In England, The Who and the Small Faces were the bands most closely associated with the Mods. It was a movement that began with fashionable young people in London who were interested in clothes and R&B music. It soon spread throughout Great Britain, but during the “Swinging London” period of the late 1960s, the popularity of the original Mod styles began to fade. At the same time, the psychedelic hippie style grew in influence, impacting the look of Mod bands, including The Who.

This was reflected in the stage clothes the band wore on their appearances on Murray the K’s Music in the Fifth Dimension shows. Purchased from the Granny Takes A Trip boutique on Kings Road in London, items included velvet and satin trousers along with jackets, shirts, and ties with bold floral patterns. Pete Townshend wore a self-designed electric jacket consisting of tiny flashing lights that were connected to the same circuit as his guitar.

The Who’s New York debut and the publicity campaign that preceded it seemed to work as “Happy Jack” reached # 24 on Billboard’s Hot 100, becoming The Who’s first Top 40 hit in the U.S.A. The single also drove the American release of the band’s second album that had already been issued in England as “A Quick One” in December. The album was released in America five months later and retitled “Happy Jack” to take advantage of the single’s success. It became the first Who LP to chart on the Billboard 200 when it reached # 67.

While the band was in America, managers Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp were putting the finishing touches on their own label, Track Records. Besides The Who, the new label had signed two then-unknown acts, The Jimi Hendrix Experience and The Crazy World of Arthur Brown. They also began making plans for The Who’s first American tour in the summer to promote the band’s next single.

A-Square Records released the “I’m So Glad single in May. WKNR-FM helped break the record into a Top Ten hit in Detroit, and it reached # 1 on Flint’s influential WTAC-AM. Although the band wasn’t completely happy with the recording, the airplay increased their draw and playing fee.

“After “I’m So Glad” became a hit, a lot more people started coming to the gigs.” Steve Lyman recalled. “The amount we were paid went up as well. The early gigs might have paid us around $100 for the whole band. It might have gone up to $500 after the hit.”

As the summer approached, the Scot Richard Case hired two roadies to help with the band equipment. Tom Shoemaker had attended high school in Royal Oak and knew Glenn Frey when he was in The Subterraneans. Frey spoke to Scott Richardson and recommended Shoemaker and his friend Barry Bollock for the jobs.

“The Scot Richard Case came to my house and picked us up in their 1966 Dodge van with the band name on the side,” Tom Shoemaker remembered. “They took us to the band house in Ann Arbor and explained to us what they wanted. ‘I’m So Glad’ was a big hit that summer. At that time, they played all covers, no original songs. The hit made the Scot Richard Case the band to see, and we had standing room only crowds all over the place. Our job was to put up all of the amps and the small P.A. that we had and then break everything down. We had a little trailer for the equipment. It was a lot of work, but it was so much fun.”  The Broadway Street house in Ann Arbor (L-R) Gary Quackenbush, E. G. Clawson, Robin Dale, Scott Richardson

The Broadway Street house in Ann Arbor (L-R) Gary Quackenbush, E. G. Clawson, Robin Dale, Scott Richardson

“The band house of Broadway had one room that was covered with cardboard egg cartons. If you went outside, which was about five feet to the sidewalk, you could barely hear them rehearsing,” Shoemaker recalled. “That was the way they wanted it. They didn’t want to disturb anybody. Barry and I lived in the house with the six band members.”

“Every musician in the band was excellent, and their popularity was off the charts,” Shoemaker said. “They were bigger than Seger, The Rationals, anybody in Michigan. At the time, the Scot Richard Case was ‘the band’ in Detroit along with Mitch Ryder and The Detroit Wheels. They played on Swinging Time at least a half dozen times while I was there. Robin Seymour really liked them, so he gave them a lot of exposure.”

Manager Jeep Holland stressed the importance of live performances, and he helped the Scot Richard Case develop a stage presentation that combined stellar musicianship with plenty of showmanship and visual flair. “I loved Jeep. He was a good guy, but he was hard,” Shoemaker said. “We would come back from a two or three-day tour around Michigan at 1:00 in the morning, and he would say: I heard that you guys didn’t play that well, so get out your gear and we’re going to practice for a couple hours.”

Following their appearance with Murray the K in New York, The Who flew home to record their new single, “Pictures of Lily.” The band then began a two-month tour of Germany, Scandinavia, and England before a planned return to America in the summer.

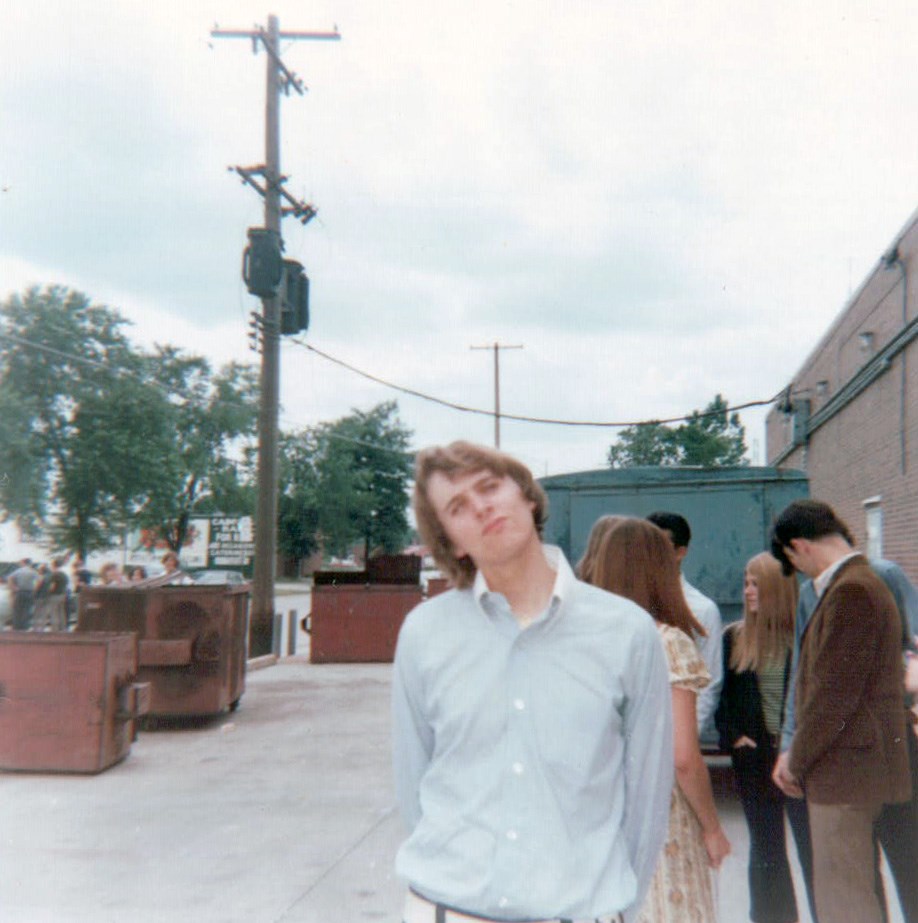

After arriving in Detroit on June 13, The Who reportedly partied with Mitch Ryder who had headlined the shows in New York with Murray the K. The following day, The Who was booked to do two shows at the Fifth Dimension club in Ann Arbor.  Pete Andrews

Pete Andrews

It was local impresario Pete Andrews that booked The Who’s first Michigan show. Andrews had started out booking bands for fraternity and sorority events at the University of Michigan, and that was how he met Jeep Holland. Andrews opened Mother’s in 1965 in the Ann Arbor Armory on Ann Street. It was the city’s first teen club, and Holland helped Andrews line up the bands. This led to a partnership between the two men wherein Andrews co-managed The Rationals, The Thyme, and The Chosen Few.

The Who was scheduled to play afternoon and evening shows at the Fifth Dimension on June 14th, but their equipment didn’t arrive at Detroit’s Metro Airport in time for the early show. “We had some pretty good equipment that included a sound system that was portable enough to bring down to the Fifth Dimension, and we had volunteered it ahead of time so it was there when The Who arrived,” Steve Lyman recalled. “The Who was able to play the afternoon show because the Scot Richard Case volunteered its equipment that included a Vox Super Beatle amplifier, a Sunn amp, and E.G.’s drums for Keith Moon.”  Hugh "Jeep" Holland

Hugh "Jeep" Holland

The Thyme, opened for The Who at the Fifth Dimension. The band had formed in Kalamazoo as The Hitch Hikers before changing their name and basing themselves in Ann Arbor under the direction of Jeep Holland. Early in 1967, The Thyme recorded an excellent version of Neil Diamond's "Love To Love," and Holland managed to to secure a national release for the record on Bert Berns' Bang label. Later in the year, The Thyme opened for both the Jimi Hendrix Experience and The Yardbirds at the Fifth Dimension.

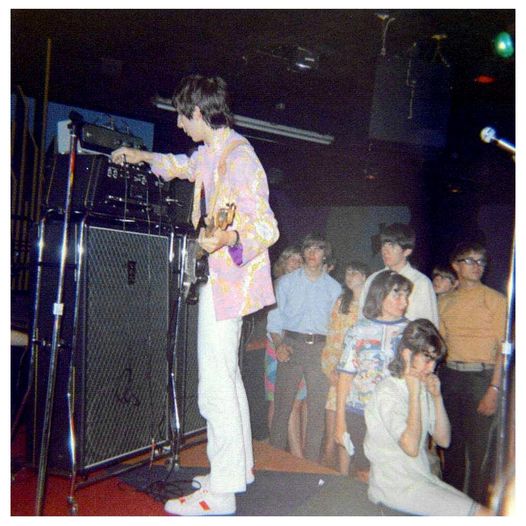

The Who’s equipment arrived in time for the evening performance, and it was at that show that they fully demonstrated their power as a live act. “They used buckets of dry ice with coloring added to produce clouds during ‘My Generation’ with Keith Moon going nuts on the drums and kicking over things,” Tom Shoemaker recalled. “The place was packed with guys and girls screaming. It was awesome!” Steve Vandenberg of The Thyme also clearly remembered The Who's closing number. "It was just chaos," he recalled. "The security guards had not been informed that Townshend was going to be smashing his guitar and Moon was going to kick over his drums. They thought the band had lost its mind."

Pete Townshend on stage at the Fifth Dimenson

Pete Townshend on stage at the Fifth Dimenson

“Scott Richardson became friends with Pete Townshend at the Fifth Dimension,” Shoemaker said. “Townshend asked him if there was any place they could store their guitars since he didn’t trust the hotel they were staying. Scott told him about the band house in Ann Arbor and offered to keep them overnight. The Who came to the house and dropped off the guitars and then left to party at their hotel with the Scot Richard Case.”

“The Fifth Dimension was only two miles from our rented house,” Steve Lyman said, “and the hotel where The Who stayed was less than a mile from our house. The one thing I remember of Townshend was that he stayed in his room while we were hanging out at their hotel’s swimming pool. We heard that he was writing a rock opera.”

“Barry and I stayed behind,” Shoemaker remembered. “We opened up Townshend’s guitar case and there was blood all over the guitar, probably from twirling it and hitting the strings with his fingers. The one guitar that he used to smash on stage was kind of built up so that it wouldn’t completely disintegrate – the same with John Entwhistle’s bass. He was all over that bass, and it was covered with different stickers from the places they played. The Who wasn’t real well known at that time, and neither was Jimi Hendrix.”

That would change four days later when both The Who and the Jimi Hendrix Experience closed the third and final day of the Monterey International Pop Festival. The Who’s dramatic performance of “My Generation,” and the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s incendiary cover of “Wild Thing” were both captured by filmmaker D.A. Pennebaker and were highlights of his Monterey Pop documentary film.

After the festival, The Who flew back to England for John Entwistle’s marriage and to work on songs for a new album. They also recorded covers of two Rolling Stones’ songs, “The Last Time” and “Under My Thumb,” to show their support of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards who had been convicted of drug offences and were facing harsh prison sentences.

On July 13th, The Who returned to the United States to begin a ten-week, coast-to-coast American and Canadian tour in support of Herman’s Hermits. On August 23rd, the tour played Atwood Stadium in Flint, Michigan, with the Blues Magoos and The Who as the opening acts. In his book Local DJ, Peter C. Cavanaugh wrote that The Who’s powerful, take no prisoners performance completely overshadowed the headliners.

Following the concert, the tour celebrated Keith Moon’s 21st birthday with a wild party at the Holiday Inn where they were staying. Although everyone is in agreement that the party had quickly gotten out of hand, there is some disagreement over whether the event’s most infamous incident actually happened.

According to unconfirmed and possibly exaggerated reports, the sheriff’s office was notified after fire extinguishers were turned on cars in the parking lot, televisions were thrown in the swimming pool, and two changing cubicles were damaged. Premier Talent and Decca Records had presented Moon with a five-tiered cake, which he proceeded to hurl around the party. Moon was said to have mistakenly hit the sheriff with a piece of the cake after the person he was aiming at ducked.

Barbara Bacon was a shy 16-year-old when she attended the party with her older sister, Char. They didn’t go to the concert, but she said her sister was friends with Ron and Scott Asheton and various Ann Arbor group members. “It was likely the SRC connection got us into the party,” Barbara recalled. “We knew their manager, Peter Andrews. It was very exciting. I did see Herman (Peter Noone) of the Hermits start throwing the cake, but I wasn’t there when the cops showed up. I didn’t see the Keith Moon incident but I certainly heard about it.”  Pete Andrews, Peter Noone, and Keith Moon at the Flint Holiday Inn birthday bash

Pete Andrews, Peter Noone, and Keith Moon at the Flint Holiday Inn birthday bash

In a 1972 interview, Keith Moon told Rolling Stone magazine that he had stripped to his underwear during a food fight at the party and ran out when the hotel manager stormed in. Moon was so drunk that he tripped while running around the room and chipped off part of a front tooth. The sheriff later drove Moon to a local dentist who had to operate on him without any anesthetic because he was so inebriated.

“I ran out, jumped into the first car I came to, which was a brand-new Lincoln Continental, " he told writer Jerry Hopkins. "It was parked on a slight hill, and when I took the handbrake off, it started to roll and it smashed straight through this pool surround (fence), and the whole Lincoln Continental went into the (Holiday) Inn swimming pool, with me in it."

Bassist John Entwistle, however, claimed that it never happened; and in 2013, the Huffington Post published an article that debunked it as an urban legend. But Peter C. Cavanaugh wrote in his book that Moon had driven the car into the pool after the post-concert party had “deteriorated into a birthday cake-throwing food fight.” He stated it again in an interview with the Flint Journal in 2013. “I was there. I saw it halfway in the pool and halfway on land.”  Scott Richardson

Scott Richardson

Scott Richardson attended both the concert and the birthday party. “I got to be friendly with Pete Townshend, and there are several stories about this,” Richardson recalled. “One is Keith Moon driving the Lincoln Continental into the pool at the Holiday Inn. I was there and I witnessed it. I was sitting next to Pete Townshend when it happened.”

“There were four of us, Pete Townshend, Teddy Thompson, one other person and myself sitting by the entrance in the nine-person Dodge van. It was the vehicle that our band traveled in,” Richardson recalled. “Pete had a hash joint. It was what they used to smoke it those days. It was hashish and tobacco rolled together, and it was a favorite of English musicians. While we were smoking this joint, Pete was complaining that their recent single, “Pictures of Lily,” was a complete bomb, only reaching # 51 in the United States.”

“As we’re having this conversation, ‘boom, bang, bang!’ Keith drives into the pool with this Lincoln Continental after smacking into three or four cars to go through the archway of the Holiday Inn. We saw the whole thing happen,” Richardson said.

Keith Moon was back at it on September 15, when The Who taped a guest appearance on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour in the CBS Television Studios on Sunset Boulevard. The band mimed an edited version of their exciting new single, “I Can See For Miles,” followed by a recut version of “My Generation” with Roger Daltrey’s live vocal and a feigned smash-up ending.

Unbeknownst to anyone in the studio, Moon had filled one of his bass drums with flash powder well in excess of safety levels. When it was set off at the climax of “My Generation,” the explosion literally shook the cameras and blew out the studio monitors. Pete Townshend, who was closest to the blast, took the full brunt and temporarily lost his hearing, while Moon suffered a three-inch gash in his arm.

The episode aired two days later on September 17th. It was a very memorable debut on national television for The Who, and Decca Records rush-released the “I Can See For Miles” single the following day to take full advantage of their appearance. Watch The Who's "My Generation" performance on The Smothers Brothers:

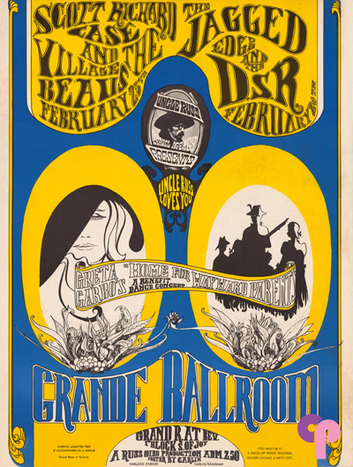

It was during this time that the Scot Richard Case underwent some major changes, including the decision to shorten the band’s name to SRC. “The mistakes in spelling the Scot Richard Case might have been part of the reason for changing the name to SRC,” Scott Richardson said. Misspelling of the band name, usually by adding and extra ‘t’ to Scot, were printed on numerous posters and newspaper ads for gigs, including their first at the Grande Ballroom.

“We didn’t make a point of demanding it be spelled correctly,” Steve Lyman recalled. “Even after we shortened to SRC, people would put periods behind the letters like initials. We didn’t want that. We wanted just the three letters and no “The” before them. The primary reason behind it is, as a band, we came to the idea that the band shouldn’t be named after just one person. It should represent the whole group. By that point, a lot of people were abbreviating it to the three letters anyway.”

The band also replaced Holland as their manager with Pete Andrews. In his book, The Joint Was Jumpin’: A Promoter’ Story, Andrews wrote that the band’s problem with Jeep was over artistic control. He stated that he liked Holland and his music business smarts, but they had different work styles and the partnership ended when he took over the exclusive management of SRC. Pete Andrews was a good fit for SRC at this time. He was skilled at booking gigs for the band, and he didn’t interfere with their music.

“We went into another phase that had to do with psychedelics and things like that,” Richardson said. “The breakup with Jeep Holland came about because the direction the band was moving musically was completely counter to what he wanted us to do.”

“We were ensconced in the hippie mythos of cooperation with everyone because that was what was happening at the time in the music we were making and in the cultural revolution that was taking place,” Richardson said. “It was really intense. The summer of 1967 was when Pink Floyd’s “Piper At The Gates Of Dawn” was released along with Procol Harum’s “Whiter Shade of Pale”, Jimi Hendrix and “Are You Experienced”, and of course “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.” They all happened that summer, and it was so influential for us. We could play that music. Not a lot of other bands could.” (L-R) Glenn Quackenbush, Robin Dale, E. G. Clawson, Steve Lyman, Scott Richardson, Gary Quackenbush

(L-R) Glenn Quackenbush, Robin Dale, E. G. Clawson, Steve Lyman, Scott Richardson, Gary Quackenbush

“SRC was influenced by the great English bands, and they were the most classically Mod of all the Detroit bands,” Andrews wrote in The Joint Was Jumpin’. “It wasn’t unusual for the group to go to New York to shop for clothes. They had boots custom made in Toronto. No Michigan band could match their equipment or style.”

“We got a lot of our stage clothing from New York at Paul Sargent’s and the Brick Shed House in Greenwich Village, and at Granny Takes A Trip in London,” Scott Richardson recalled. “We used to have a friend, a mystical figure in Detroit named Steve McCann, who would travel to London and buy snakeskin boots, velvet pants, and jackets and bring them back for us.”

“The British look was part of our appeal,” Steve Lyman said. “Scott Richardson had a flashing light jacket. It was really Christmas lights that were sewn into the jacket, and he was plugged into a 100-volt outlet through a couple of extension cords. I’m not sure when he started wearing it, maybe in the fall after seeing The Who. We also started using colored (yellow, red, and green) smoke bombs in the fall of 1967.”

Following their Smothers Brothers’ appearance, The Who returned to England to undertake a theatre tour with Traffic, The Tremeloes, and The Herd, featuring 16-year-old guitarist Peter Frampton. They also finished recording tracks for their upcoming album, “The Who Sell Out,” that was scheduled to be released at the end of the year.

On November 15th, The Who flew to the United States for a two-week visit. “I Can See For Miles” peaked at # 9 on Billboard’s Hot 100 the week they arrived; and it was the first time that American audiences saw them play the song live.

The Who’s fifth appearance on their American visit that fall was a concert at the Southfield High School gymnasium. It was their third and final Michigan show of 1967, and it featured opening sets by the Unrelated Segments and the Amboy Dukes. The members of SRC attended the show, and that may have been when plans were hatched to fly to the East Coast to see The Who’s concert at Union Catholic High School in Scotch Plains, New Jersey.

“The reason for the flight out East was two-fold,” Scott Richardson recalled. “We wanted to see The Who and also visit the Ultra-Sound studio on Long Island where Shadow Morton often worked. We were interested in the records he did with The Shangri-Las.”

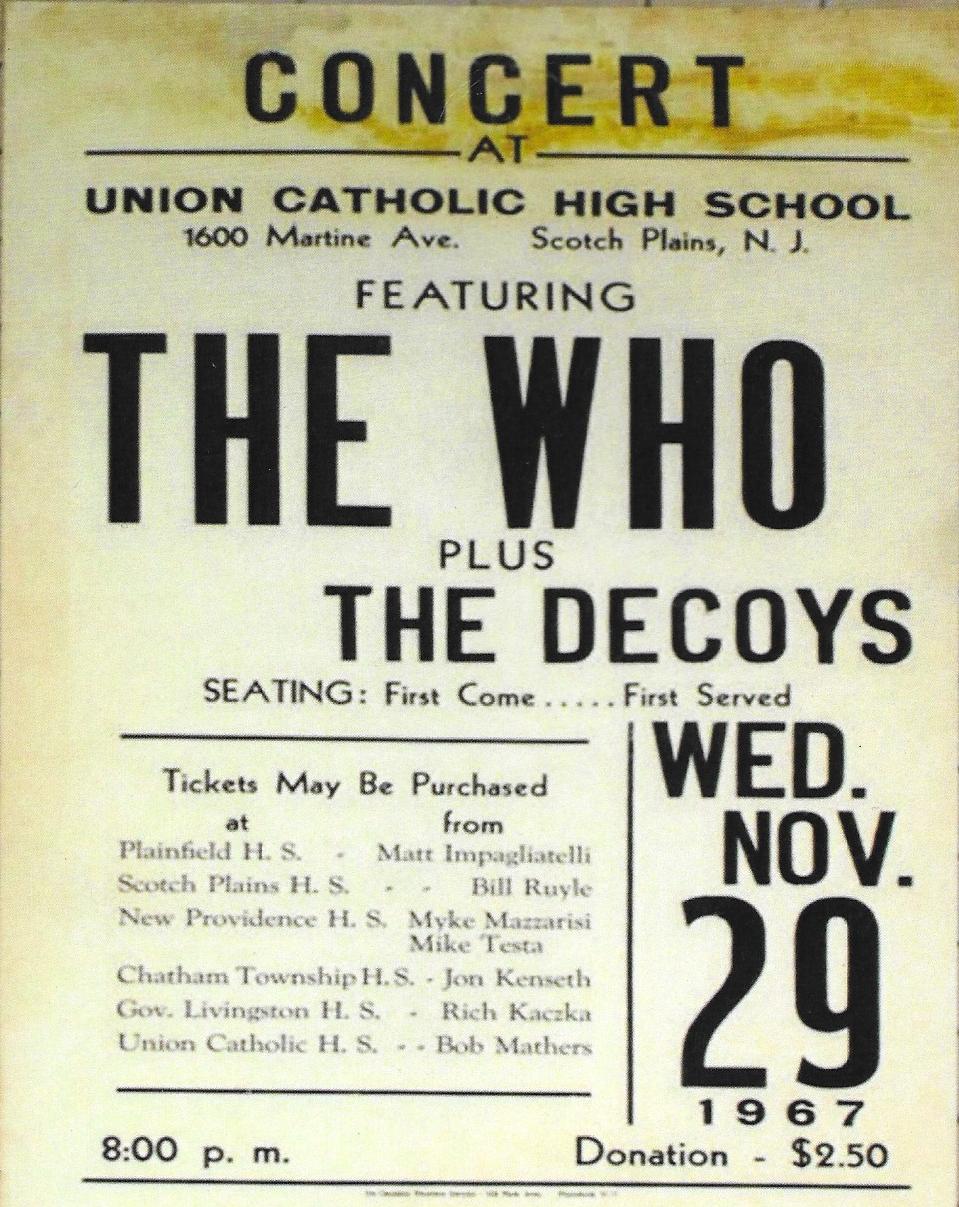

Union Catholic was probably the most unlikely place to host The Who during their American visits in 1967 but, thanks to a die-hard Who fan named Michael Rosenbloom, we have more information about the band’s appearance there than at any other venue that year. After completing a great deal of research that included numerous interviews with the people who organized and witnessed the event, Rosenbloom wrote a short book titled When Stars Were In Reach: The Who At Union Catholic High – November 29, 1967.

Published in 2013, the author revealed a behind-the-scenes look at one of the band’s concerts during a more innocent time, before rock and roll became a big business and The Who was still in the early stages of climbing the ladder to commercial success in the United States.

Opened for the 1962-63 school year, Union Catholic was located about 30 miles west-southwest of Manhattan. It housed separate boys’ and girls’ high schools with separate faculties and administrations. Rosenbloom described it as a regional high school that served the educational needs of Catholic families from all over Union County, and it was populated by college-bound young people from mostly white, middle class suburban families.

The U.C. boys’ school was run by Marist Brothers, a teaching order within the Catholic Church with a mission to encourage their pupils to think for themselves. The students who organized The Who’s concert lived up to that mission by forming a concert committee, contacting a booking agent in New York, and presenting the idea to the administration as fundraiser for the school.

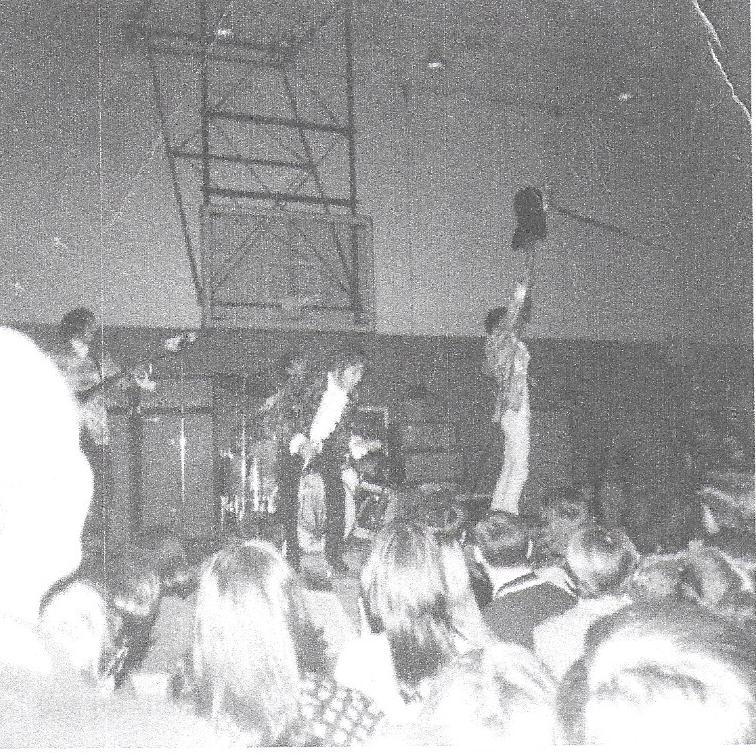

Their proposal was accepted, and they were allocated a total budget of $3,000, which included $1,800 for The Who and the rest for the expenses of staging the concert. With tickets priced at $2.50, the concert attracted a crowd of 2,200 who witnessed an electrifying performance by the headliners that included Pete Townshend smashing his guitar during the “My Generation” finale. (L-R) John Entwistle, Keith Moon, Roger Daltry, and Pete Townshend about to smash his guitar at Union Catholic

(L-R) John Entwistle, Keith Moon, Roger Daltry, and Pete Townshend about to smash his guitar at Union Catholic

Not only was The Who concert the most exciting event that had ever taken place at Union Catholic, it was also very profitable. Rosenbloom wrote that the concert grossed over $6,000 and, after deducting expenses, the school enjoyed a profit of $3,100. In addition, the success of this first event led to a series of concerts during the next few years at U.C. that featured appearances by Cream, The Lovin’ Spoonful, Iron Butterfly, Chicago, Blood Sweat and Tears, The Association, Steppenwolf, and Black Sabbath. They ended in 1971 when rising costs put the school out of the concert business.

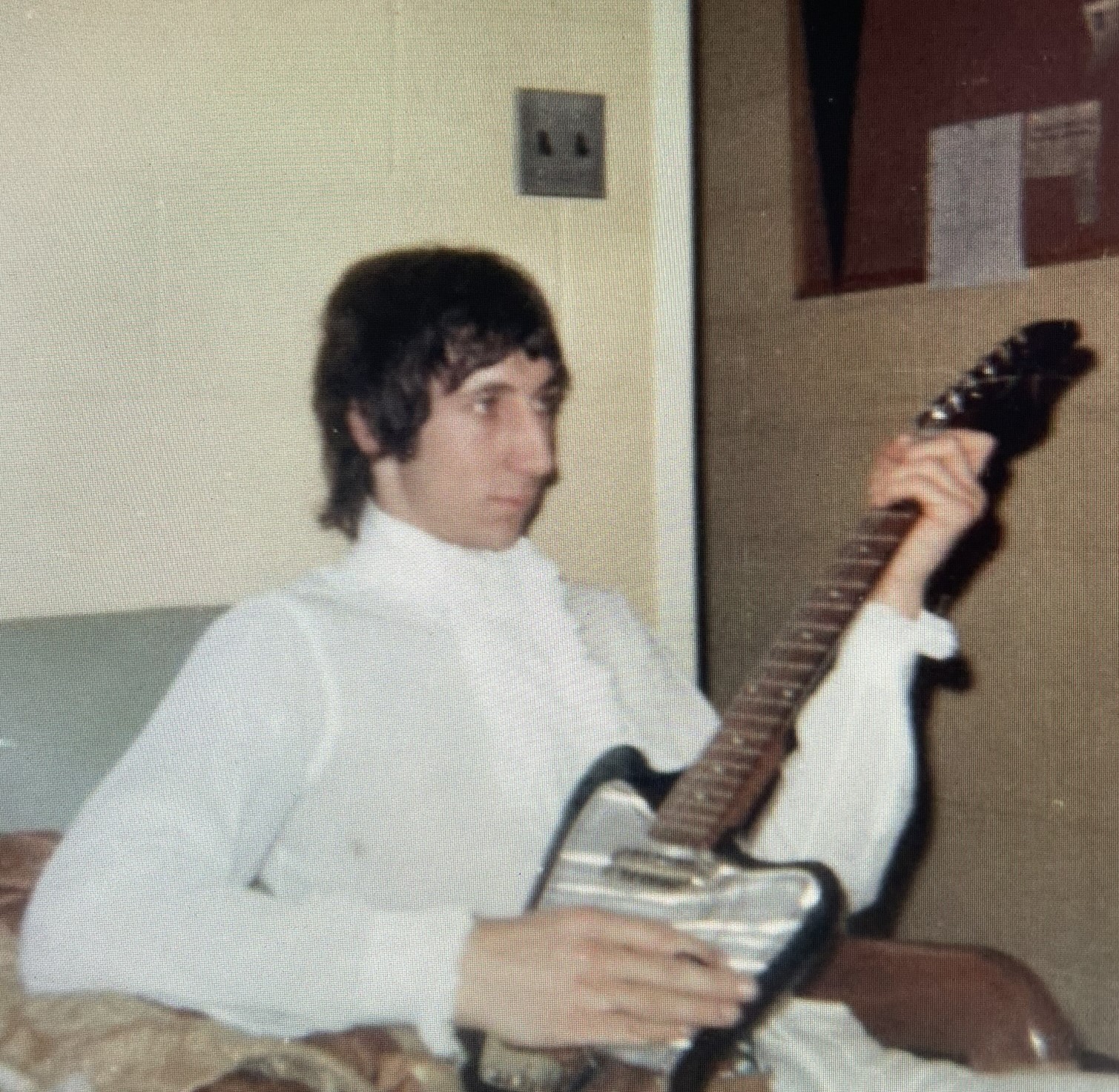

A review of the Who concert, titled 2,200 Witness A "Who” Happening In High School Gymnasium, appeared a few weeks later in The Terrier, the Union Catholic’ boys' newspaper. The members of SRC and their manager must have made quite an impression because a full paragraph in the report was devoted to them: “Perhaps the most outstanding part of the entertainment was that provided by about a dozen of The Who’s personal friends – bearded, in lace, shag-eared, hippy, and from Michigan. Although this long-haired group, who occupied most of the first row of seats in the audience, seemed in a state of suspended animation while The Decoys played, they came to life when The Who vaulted to the stage. Punctuating shouts of ‘The Who’ with an occasional scream, they gyrated in wild ecstasy to ‘My Generation’ and ‘Pictures of Lily’.”  Townshend with his Cornet Hornet guitar in the Union Catholic teachers' lounge that was used as The Who's dressing room

Townshend with his Cornet Hornet guitar in the Union Catholic teachers' lounge that was used as The Who's dressing room

“We got in early before the crowd arrived,” Steve Lyman recalled. “We were near the front of the stage, and because we were dressed in Mod style with long hair, we were sure that The Who would notice us. The entire band plus Pete Andrews and possibly one of our roadies were there.”

“We didn’t talk to The Who after the show, but we followed their bus in a rented car,” Lyman continued. “It pulled over to the side of the road and Pete got out of the bus while we were parked several car lengths behind; and he yelled “Are you the guys from Ann Arbor?” and Scott Richardson yelled ‘Yeah’. Townshend then put his fist in the air and yelled ‘Yeah’ in return. They then headed to their hotel and we drove back to our hotel because we had to get up early to go to Long Island.” It was the last time the two bands would see each other in 1967, but their interactions would lead to a very intriguing offer in early 1968.

The Who played one more American show in Long Island on December 1, before returning to England for the release of “The Who Sell Out” album. The band’s most creative and psychedelic album yet was a collection of songs interspersed with fake commercials recorded by the group to give the impression of a pirate radio station broadcast. Although it received some glowing reviews and was preceded by its hit single, “I Can See For Miles,” the album’s concept was mostly lost on record buyers in the United States; and “The Who Sell Out” peaked at # 48 on the Billboard 200.  The Who at Union Catholic High School

The Who at Union Catholic High School

In the meantime, SRC was looking for a record deal. “John Rhys was part of the connection with Capitol Records,” Steve Lyman remembered. “He was a local producer in Detroit who had worked with Edwin Starr and had produced the hit “Oh How Happy” by The Shades of Blue for Harry Balk’s Impact label.”

“When Pete Andrews found out about him, he took us over to Rhys’ apartment in Detroit to meet him in early 1968. I recognized him as the same producer I had met back in the summer of 1965 when my former band, The Ravens, had visited the Golden World Studios.”

“After John Rhys came to hear us practice and listen to our ideas, he contacted Herb Hendler who was pretty high up at Capitol Records and was the head of Beechwood Music, which was Capitol’s publishing company,” Lyman said. “He told Hendler to come to Michigan to hear our band play.”

“Hendler flew to Michigan, met us, and came to a couple of gigs. He was excited about us. We thought we were going to become really big, but you never really know,” Lyman said. “We were trying to figure out what was the best kind of recording deal to get. Capitol Records had really good distribution, but there was also an interesting offer from The Who’s label, Track Records.”  Chris Stamp and Kit Lambert of Track Records

Chris Stamp and Kit Lambert of Track Records

“Pete Townshend had become interested in us, and later at the Fifth Dimension we had a private audition for their manager, Kit Lambert, who flew over to Michigan from England to see us,” Scott Richardson revealed. “He loved us and then came to the house with his briefcase and told us about his new label, Track Records, that was going to have The Who on it. He also had two acetates with him, and he said these are two artists I also have on my label. The first he played for us was ‘Fire’ by The Crazy World of Arthur Brown and the second was ‘Hey Joe’ by The Jimi Hendrix Experience.”

“Kit Lambert told us that Pete wants you to go to England, and he wants to produce you in England and tour over there.” Richardson said. “Kit told us, ‘Your band is phenomenal, I just love your band!’ We had a choice between taking that deal, and this is the cosmic moment that happens in the case of many bands, where there comes a crossroads and a decision to make in what direction you are going to go.”

“At the same time, we got the offer from The Who’s label to be the first American band to be signed by Track Records, we also had an offer to sign with Capitol Records and have John Rhys produce us,” Richardson said. “We ended up voting and choosing Capitol because they were distributing The Beatles. We thought that’s that, and so we passed on that opportunity. I love John Rhys and the records he made with us, and I love what happened to us and where we went, but who knows what would have happened if we had Pete Townshend produce our first single. It’s just one of those things you’ll never know, but it’s an interesting thing to contemplate.”

“It was very unusual in the rock and roll business for artists to have friendly relationships with other bands. Everyone was in competition so it was really unique and cool that Pete had taken an interest in us,” Richardson said. “It was really great but, unfortunately, we didn’t act on it. It’s just one of those things in history where who would have known what could have happened? At the time, it was mind-blowing for us to be able to hang out with The Who and get that kind of feedback and have those crazy adventures,” Richadson said.

“When we started talking to Track Records, we really liked the idea of them being connected to The Who and other British groups, but they didn’t have the worldwide distribution that Capitol had through EMI,” Lyman said. “That’s probably why we settled on Capitol. We thought we were getting a good deal but like with all recording contracts, you find out later that we got screwed.”  John Rhys

John Rhys

SRC released its self-titled debut album on Capitol Records in September of 1968. It was recorded at the Tera Shirma Studios in Detroit and produced by John Rhys. The “SRC” album was a big hit in Michigan, and it sold enough copies nationwide to spend four weeks on the Billboard 200 where it peaked at # 148. Capitol also issued a shortened version of “Black Sheep” as a single. It was also a big hit in Michigan but it failed to chart nationally.

The band’s second album, “Milestones,” was released in March, 1969. The album spent nine weeks on the Billboard 200, peaking at # 134, but once again, SRC did not come up with the hit single necessary to push the album into the Top 40. The band's lineup had gone through some changes by the time that their third album,"Traveler's Tale," was released in 1970. When it failed to chart, SRC was dropped by Capitol Records.

“I wasn’t happy with the way that Capitol promoted the band or how any of that was handled,” Richardson said. “I realize now that we were shot-gunned, and that Track Records would have been the artistic way to go. But it was totally scary for us in that our home base was in the Midwest, and we had a really good business going. People loved us live, we were making money, and we were living communally like the band Love was out in L.A. and how people were living in San Francisco too.”  SRC later lineup (L-R) Al Wilmot, Gary Quackenbush, Glenn Quackenbush, Scott Richardson, E. G. Clawson

SRC later lineup (L-R) Al Wilmot, Gary Quackenbush, Glenn Quackenbush, Scott Richardson, E. G. Clawson

“We were living that dream of being in the same house as our music, making it all day long, and succeeding at it. The story of SRC boils down to one thing and one thing only,” Richardson said. “We didn’t have strong enough management. Pete Andrews was a great promoter of shows and getting us booking, but as far as the artistic idea of management that came in later in the rock era, we were all making shit up at that time. It was all brand new; nobody had ever done this before.”

In his The Joint Was Jumpin’ book, Pete Andrews wrote: “I have to say that Capitol Records never did anything to promote the group. Even though the band sold what today might be considered a lot of records, it wasn’t enough then to continue the relationship with Capitol. As it turned out, we probably should have signed with Track, but we couldn’t know at that time. We took what we thought was a safer bet.”

Of his time managing the band, Andrews wrote that he only had fond memories. “My experience managing SRC I would never take back. Those great guys taught me a lot. It was an exciting time!”

Afterword:

I became interested in this story after Steve Lyman revealed on the Michigan Music History Podcast that SRC had traveled to New Jersey in 1967 to see The Who’s performance at Union Catholic High School in Scotch Plains. My oldest grandson, Connor, attends the school; and I was curious to see if the school had any record of the concert.

A few weeks later, my son Brennan noticed that the school had an enlarged copy of the article in The Terrier about The Who’s appearance from 1967 in one of the glass cases that display the school’s history along the second-floor hallway, and he sent me a photo. I was intrigued by the paragraph devoted to what the writer described as “The Who’s long-haired group of personal friends from Michigan.”

I purchased a Kindle copy of Michael Rosenbloom’s book, and I read it before my wife and I scheduled a meeting with some of Union Catholic’s current administration on December 4, 2023. Rosenbloom had no way of knowing that the Michigan fans in the article in the school paper was SRC, so there was no mention of them. It’s too bad because I’m pretty certain that he would have reached out to the surviving band members, discovered the interesting story of their connection with The Who and included it in his book.

On the morning of December 4th, my wife and I met our grandson for the annual Grandparents’ Breakfast in the school cafeteria. Following the breakfast, Lynn and I met with Assistant Principal Dr. James Reagan and Information Director James Lambert who led us on a tour of the school where we met Percylee Hart, the Union Catholic Principal, and Nancy Foulks, the Director of Alumni. Nancy showed us the Witness Yearbook from the 1967-68 school year that had two full pages of photos of The Who and the concert. She also generously sent me a file of those photos.

Union Catholic High School is much the same as it was in 1967. It’s a beautiful, well preserved learning institution in an idyllic setting. The school is now co-educational, and the Marist Brothers have not been in charge since 1975. Although there have been some additions to the school over the years, it felt a little like we were entering a time capsule during our visit. The gymnasium where the concert took place is almost exactly as it was back in 1967.

A week after our visit, Lynn and I attended a Union Catholic basketball game. We sat in bleacher seats at the end of the gymnasium where the stage was set up for the concert. It would have been to the left of the stage on the side closest to where John Entwistle stood.

I had only witnessed The Who perform in very large venues in Michigan, and I was struck by how close I would have been to the band if I have been in the very same seat back in 1967. I also pondered how lucky those concert attendees had been to see The Who that night at the cusp of becoming one of the most important bands in rock and roll.

Sources:

Interviews by phone and/or text with Barbara Bacon, Steve Lyman, Scott Richardson, and Tom Shoemaker.

The Fugitives SRC webpage by Bruno Ceriotti

Anyway Anyhow Anywhere: The Complete Chronicle of The Who 1958 – 1978 by Andy Neil and Matt Kent

When The Stars Were In Reach: The Who at Union Catholic High School November 29, 1967 by Michael Rosenbloom

The Joint Was Jumpin’: A Promoter’s Story by Pete Andrews

Local DJ: A Rock "n" Roll History by Peter C. Cavanaugh

The Fifth Dimension, Ann Arbor Chronicle by Frank Uhle

Photos taken by Joan Hadley McCartney of The Who at Union Catholic