Mitch Ryder was born William Levise Jr. in 1945, the second of eight children in the mainly Polish working-class city of Hamtramck, Michigan. While he was still quite young, Mitch's family moved to Warren, Michigan, near 9 Mile Road. The Levise family would eventually move to houses located on both 12 Mile and 11 Mile Roads while Mitch was growing up.

Mitch’s father, William Levise Sr., was a Big Band era singer who performed on radio in the late 1940’s and worked for a few small record companies in the Detroit area. Mitch's mother was not only a housewife, but an aspiring songwriter as well. There was always a lot of music in the Levise household, either from William Sr.’s collection of 78-rpm records, or on the family radio. It was on that radio that an 11-year-old Mitch would first hear the new sounds of Rock and Roll.  Billy Lee & The Rivieras: Billy Levise, Earl Elliott, Joe Kubert, Jim McCarty, John "Bee" Badanjak

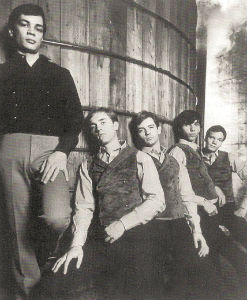

Billy Lee & The Rivieras: Billy Levise, Earl Elliott, Joe Kubert, Jim McCarty, John "Bee" Badanjak

In junior high, Mitch befriended Joe Kubert, a budding guitarist. The boys shared a mutual love of music, especially Rhythm & Blues. Mitch and Kubert would go on to form a band when they got into high school called the Tempest.

Mitch's first taste of performing came during his sophmore year at Warren High School. He sang the Johnny Mathis hit "Chances Are" during a school assembly, and he was immediately hooked by the audience's applause and cheering. His high school music teacher then entered Mitch in a tri-county music tournament. His victory earned him a scholarship to a summer music camp.

From that point on, Mitch began singing whenever he could, at any venue that would have him. He shortened his last name and began performing as Billy Lee. His father had always been supportive of his son’s interest in music, and when Mitch turned seventeen, his dad put up the money for him to record a Billy Lee single.

The record was put out on a small independent black-owned label called Carrie Records. Owner James Hendrix had only issued a few gospel records on his tiny label. Hendrix wrote a song called “That’s The Way It’s Gonna Be” for one side of the 45-rpm, and Mitch wrote a blues ballad called “Fool for You’ for the other. Although the record got only minimal airplay, it opened some doors for Mitch.

Mitch began hanging out at a Detroit music club called The Village, located on Woodward Avenue. There, he began performing in an interracial vocal group called the Fabulairs along with two black singers who worked at the club, Joe Harris and Ronnie Abner. Besides singing together at the Village, the Fabulairs sang a capppella sets on the boat to Bob-Lo Island, the famous Detroit River amusement park. Soon after, Harris and Abner would add Tom Storm to their line-up and rename themselves the Peps.

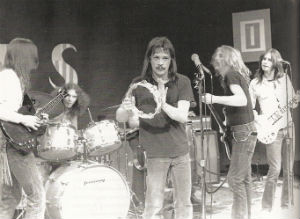

Inspired by the success of the Beatles, Mitch and his old pal Joe Kubert joined forces with the Rivieras, the house band at the Village. The Rivieras were made up of guitarist Jim McCarty, bassist Earl Elliott, and drummer John Badanjek. Calling their new group Billy Lee & the Rivieras, the band rehearsed in the Badanjek attic at John’s parents' house, and soon landed a regular gig at the Bamboo Hut teen club. Mitch Ryder & The Detroit Wheels: Jim McCarty, Earl Elliott, Mitch Ryder, John "Bee" Badanjak, Joe Kubert

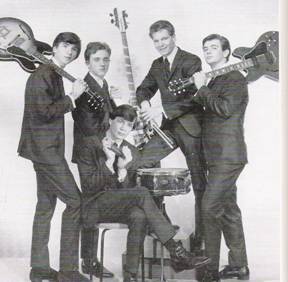

Mitch Ryder & The Detroit Wheels: Jim McCarty, Earl Elliott, Mitch Ryder, John "Bee" Badanjak, Joe Kubert

The band also became a regular attraction at the Walled Lake Casino. The Casino, built in 1919, had reopened in 1962 for package music shows hosted by Detroit deejays. Billy Lee & The Rivieras first performed in “battles of the bands” in 1964, before quickly graduating to featured act status at the venue.

Their sets would start off with some instrumentals featuring McCarty’s guitar, and then Mitch would come on with his searing vocals, knee drops, leg kicks, and anything else that would get the teen crowds going. Billy Lee & the Rivera’s hard-rocking versions of R&B and soul classics attracted a large Detroit-area following, and also the ear of Motor City deejay Bob Prince.

Prince recognized both Mitch's and the band's potential, and he began booking the group in larger venues. Their performances were so hot that they soon started headlining over even Motown artists.

Billy Lee & the Rivieras recorded their first single in 1964 on the local Hyland label. Again, Mitch’s father financed the recording of the single, “You Know" backed with "Won’t You Dance With Me”. Although it got some Detroit-area radio play, it was not the hoped-for hit record.

Bob Prince also had the band record a demo at Badanjek’s rehearsal space that eventually got into the hands of the Four Seasons’ producer, Bob Crewe. Crewe was impressed with what he heard, and he came to Detroit to watch Billy Lee & The Rivieras’ performance as the opening act for the Dave Clark Five. Crewe signed the band, and then had them move to New York City, his base of operations. The contract they signed with Bob Crewe would open the door to success, but it would come at a hefty price.

Because another group called The Rivieras had already charted with a hit called “California Sun”, the band name was the first thing to be changed. Supposedly, Billy (Mitch) was leafing through a Manhattan phone book when he happened upon the name ‘Mitch Ryder’. Thus, a new stage name was born. The band then changed their name to the Detroit Wheels, and Crewe had publicity photos taken of the group on top of oil barrels, surrounded by piles of automobile tires, to drive the Motor City image home.

Crewe lodged the five band members in two tiny rooms at the Coliseum House hotel in New York City. He kept them busy with gigs at Greenwich Village clubs and Times Square bars playing three sets per night, five days a week.

While they were building a name for themselves in the Big Apple, Mitch Ryder And The Detroit Wheels’ released their first single on Crewe’s New Voice label. “I Need Help” did not capture the excitement of Mitch and the band on stage, however, and it sunk without a trace. But their second single, “Jenny Take A Ride”, started them on a two-year journey of hits that brought the band fame and fortune, but also ended up tearing them apart.

“Jenny Take A Ride” combined two oldies, Chuck Willis’ “C.C. Rider” and Little Richard’s “Jenny, Jenny”, into a new and instantly recognizable sound that peaked at # 10 on Billboard’s Hot 100 in early 1966. According to James A. Mitchell’s book, It Was All Right, Crewe had to be talked into releasing the song as a single by Keith Richards and Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones. Richards and Jones had been guests in the studio when “Jenny Take A Ride” was recorded, and they spoke up for the song’s potential as a hit single with Bob Crewe afterwards.

The band underwent its first personnel change at this time when bassist Earl Elliott joined the Marines. He was replaced by Jim McCallister. Joe Kubert would become the next casualty as he began shooting drugs in an attempt to avoid the draft. This would lead to an addiction that would not only cost Kubert his place in the band, but also his life in 1991.

After quickly releasing their first album, “Take A Ride”, to capitalize on their hit single, Mitch and the band proved they weren’t just one-hit wonders with their next release, “Little Latin Lupe Lu”, in the spring of 1966. It became a # 17 hit, and earned the band a spot on the grueling Dick Clark’s Caravan Of Stars bus tour that summer.

Following the tour, Crewe sent the Wheels home to Detroit while he kept Mitch in New York to do photo shoots, interviews, attend meetings, and even take grooming and dancing lessons. It was the first indication that Mitch and his band were soon to be separated permanently. Mitch, who had married before leaving for New York, managed to finally break away and find the time to buy a house in Southfield, Michigan, for his wife and their baby daughter.

After the band’s next two singles, “Breakout” and “Taking All I Can Get”, achieved only minor chart success, Mitch Ryder And The Detroit Wheels went back to the formula that was so successful on “Jenny Take A Ride”. The band combined Shorty Long’s “Devil With A Blue Dress On” with another Little Richard hit, “Good Golly Miss Molly”. The combination proved to be the band’s biggest single when it peaked at # 4 in late 1966. The hit served to make Mitch an established star. Crewe quickly put out a second album, “Breakout”, to take advantage of this latest success.

Crewe’s plans for a solo career for Mitch became apparent when he repackaged the best songs from the band’s first two LPs into an album with the misleading title of “All Mitch Ryder Hits”. Later that same year, Mitch and the Wheels would record a new album titled “Sock It to Me!” that featured a close-up of just Ryder on the cover. Furthermore, it placed Mitch’s name in larger letters than the album title, while ‘the Detroit Wheels’ was mentioned in the smallest print. The photo of the band was relegated to the back of the album.

On the Top 40 front, Mitch Ryder And The Detroit Wheels quickly followed “Devil With A Blue Dress On & Good Golly Miss Molly” with another big hit. “Sock It To Me-Baby!” was released as a single in early 1967. It reached # 6 on the Hot 100 despite being banned on several radio stations for being “too sexually suggestive”. In spite of the initial flap, the term ‘Sock it to me’ ended up becoming a national catch-phrase when it began to be used weekly on the hit TV comedy show, Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In.

At this point, Mitch was now a big enough star to have a tiny ‘Mitch Ryder’ doll put on the market by the Hasbro Company as part of its ‘Show Biz Babies’ series. Crewe, by now, had disposed of McCarty and Badanjek, who went back to Detroit with some hard feelings over the way they had been treated. Ryder was not happy either, but Crewe’s contract gave him full creative control over Mitch’s career, and his master plan was to make Ryder a mainstream singing star.

McCarty and Badanjek joined up with some other musicians and recorded two singles on the Inferno label under the name the Detroit Wheels before breaking up. Jim McCarty went on to play in the Siegel-Schwall Blues Band and the Buddy Miles Express before becoming a founding member of the group Cactus. Badanjek played in a local group called Blueberry Jam. During the 70’s, McCarty and Badanjek would reunite to form the Rockets.

Crewe’s first true solo recording with Mitch was the “What Now My Love” album from 1967. Producer Crewe was obviously not tuned into the musical changes in the air during that pivotal year, nor was he in touch with Mitch’s intense desire to be an outstanding R&B singer. The resulting album was an unsatisfying mix of theatrical tunes like the title track along with some rock and roll songs played by New York session musicians. Mitch was frustrated by both the finished product and by the fact that Bob Crewe was not allowing him to create and write his own material.

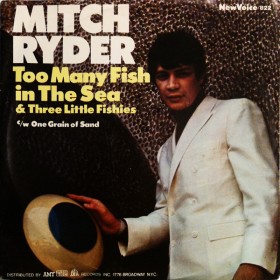

Although they were defunct, there was one last charting single credited to Mitch Ryder And The Detroit Wheels. 1967’s “Too Many Fish In The Sea & Three Little Fishes” was a medley that combined a Marvelettes’ hit with an old Kay Kyser song from 1939. The unlikely combination achieved a very respectable # 24 showing on the Hot 100.

Bob Crewe’s grand plan for Mitch Ryder’s solo career did not come close to equaling the success he enjoyed with the Detroit Wheels. The first single, "Joy", was released in the summer of 1967. It didn't stray too far from the sound of his previous hits but only reached # 41 on the Hot 100. Mitch's follow-ups, however, including the string-laden and out-of-character ballad “What Now My Love”, as well as his version of the old country song, “You Are My Sunshine”, were a far cry from the quality of the recordings Ryder made with the Detroit Wheels.

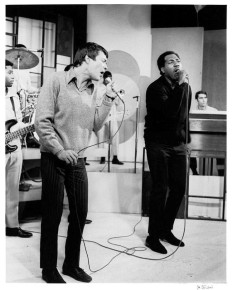

On December 9, 1967, Mitch appeared on the Upbeat television program in Cleveland along with fellow guest Otis Redding. He and Otis sang a duet on the Eddie Floyd hit, “Knock On Wood”. Mitch would be the last artist to ever perform with the soul music icon, as Redding was killed in a plane crash on route to a show in Wisconsin the following day.  Mitch Ryder and Otis Redding performing on the Upbeat television show

Mitch Ryder and Otis Redding performing on the Upbeat television show

Ryder’s last charting single with Bob Crewe again reverted back to the medley concept. This final time they combined Lloyd Price’s “(You’ve Got) Personality” with the Big Bopper’s “Chantilly Lace”. The magic of his collaborations with the Detroit Wheels was missing, however, and the song peaked at a disappointing # 87 in 1968.

Mitch was now performing live with a nine-piece horn-driven show band complete with costume changes and slick lighting and stage production. Ryder was paying the band's salaries and transportation costs, and quickly fell deep in debt. Despite selling roughly six million records for Crewe's label, Ryder had only been paid a $15,000 advance and one royalty check for $1,000.

Mitch was very unhappy with the way he felt Crewe had treated him financially. But after Crewe learned of Ryder's displeasure, he threatened that if Mitch tried to leave him, Crewe would see to it that Ryder "died musically".

Mitch and Crewe did part ways later in 1968 after Ryder took him to court to recover the royalties he believed Crewe owed him. Although Mitch lost his case, their partnership was irreparably damaged. Crewe sold Ryder’s contract to the Paramount label as a result.

Boot Hamilton first hooked up with Mitch Ryder when he was called to play keyboards at a gig in Montreal in 1969 where Mitch was being backed by several New York session musicians. Hamilton, who was born in Lincoln Park, had been playing for the past two years in drummer Sam Lay's blues band, The Mojo Workers. Following the Montreal gig Ryder, Hamilton, and the New Yorkers returned to Detroit and recorded covers of Ray Charles' "Night Time" and Chuck Berry's "Let It Rock" at the Terra Shirma Studio, but the songs were never released.

Shortly thereafter, the seeds of what what would soon grow into the band Detroit began to germinate when Ryder, Hamilton, drummer John Badanjek, bassist Tony Suhy, and guitarists Joe Kubert and Ray Goodman began rehearsing upstairs in the third floor space of the building that housed Creem Magazine. Barry Kramer, publisher of Creem, hoped to build a band around Mitch in the wake of his disheartening experience with Bob Crewe. Kramer's idea was to try to reunite the original Detroit Wheels, but he was only able to recruit Badanjek and Kubert.

Still bitter over his experiences with Crewe, and in the middle of rehearsing with the new band, Mitch left for Memphis and recorded his next album with Booker T. & The MG’s and the Memphis Horns. Titled “The Detroit Memphis Experiment”, the 1969 album was an interesting failure. “Sugar Bee” was released as a single from the sessions, but Mitch’s favorite cut was “Liberty”, his musical declaration of independence from Bob Crewe.

Following the completion of the album, Mitch was still under contract to Paramount. He returned to the Motor City to join forces with his new manager, Barry Kramer, and a revised Detroit Wheels that now included Mike McClellan and Chuck Florence on horns. The Detroit Wheels # 2 started out playing a string of small clubs, and then they undertook a short tour of the South with the musicians traveling in a 1967 Fleetwood Limousine trailed by a U-Haul truck carrying their equipment.

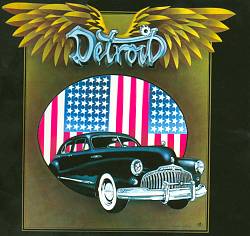

Following their less-than-successful tour, the band's name was revised. The group name was shortened to just Detroit, and the game plan was to downplay the hits that Mitch had with the Detroit Wheels and present him as simply the singer in the band as they went on a ten-day sojourn for concerts in Puerto Rico in 1969.

Boot Hamilton remembered that the band went through an assortment of guitar players as the band developed and continued to tour. Besides Kubert and Goodman, Wayne "Tex" Gabriel, Mark Manko, and Brett Tuggle also played guitar in Detroit, but finding Steve Hunter came about almost by accident.

When looking to replace Tony Suhy on bass, Boot Hamilton suggested John Sauter, who he had met in Chicago while playing with Sam Lay. Sauter was from Decatur, Illinois, and when he learned that Detroit was also looking for yet another guitar player, he suggested fellow Decatur native Steve Hunter who joined in 1971.  Detroit on stage: (L to R) Steve Hunter, John "Bee" Badanjak, Mitch Ryder, Ron Cooke, Brett Tuggle

Detroit on stage: (L to R) Steve Hunter, John "Bee" Badanjak, Mitch Ryder, Ron Cooke, Brett Tuggle

Although the turnouts at many of their shows were less than expected, the band played before roughly two hundred thousand fans at the massive Goose Lake Festival in Southern Michigan. Unfortunately, with rampant drug use and sexual debauchery being the order of the day, Detroit turned out to be undisciplined on both the road and in the recording studio. To make matters worse, the people who came to see them were unhappy that they weren't playing the old hits like "Jenny Take A Ride" and "Sock It To Me-Baby!"

The band recorded its first and only album in Chicago and Toronto with producer Bob Ezrin for the Paramount label. Hamilton and Sauter became fed up by the antics of several of their band mates, however, and left the group after recording just four songs: "Long Neck Goose", "It Ain't Easy", "Let It Rock", and "I Found A Love". They were replaced by Harry Phillips on keyboards and Ron Cooke on bass, and the album was eventually completed.

Titled “Detroit Featuring Mitch Ryder”, the LP had some stunning moments including the first single, “Long Neck Goose”, and a cover of the Rolling Stones’ “Gimme Shelter”. By far, the most successful cut, however, was the band’s cover of a Lou Reed song from his days in the Velvet Underground called “Rock ‘N Roll”. Released as a single, “Rock ‘N Roll” was a significant radio hit throughout Michigan and the Midwest in early 1972, but it reached only # 107 nationally on the Billboard Bubbling Under Chart.

Despite some positive reviews, the album failed to vault Mitch back to the position he held with the original Detroit Wheels as one of the top rockers in the country. "Detroit Featuring Mitch Ryder" only spent six weeks on the national album charts and peaked at a disappointing # 176.

After Barry Kramer stepped down as manager, Detroit was taken over briefly by John Sinclair, who first gained fame as the manager of the MC5. When Sinclair and Ryder failed to click, Mitch turned to Bud Prager, who also managed Leslie West’s power trio, Mountain. Although Prager was able to get Ryder out of his Paramount contract, he didn’t work out either.

Mitch Ryder was left without a record label or reliable management. His experiences during the last five years had left him completely discouraged. As a result, at the age of 28, one of Rock and Roll’s most promising singers decided to quit the music business and move his family to Colorado.

Although they have been passed over by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Mitch Ryder And the Detroit Wheels were among the first artists voted into Michigan Rock and Roll Legends Hall of Fame in 2005. In 2008, the band’s biggest hit, “Devil With A Blue Dress On & Good Golly Miss Molly” was voted one of Michigan’s Legendary Songs. "Sock It To Me-Baby!" was voted a Legendary Michigan Song in 2011 and "Jenny Take A Ride" in 2016.

Dr. J. Recommends:

“Rev Up: The Best Of Mitch Ryder And The Detroit Wheels”, Rhino CD. This 20 track collection has all the hits with the Detroit Wheels, along with Mitch Ryder’s key solo tracks and his two singles with Detroit. Mitch’s three original albums with the Detroit Wheels mentioned above are now available on CD with bonus tracks. All of these are worth picking up.

On the Bookshelf:

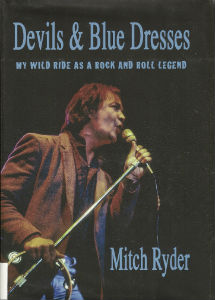

Devils & Blue Dresses. By Mitch Ryder, 2011. Published by Cool Titles, Beverly Hills, California. Ryder's no-holds-barred autobiography is probably one of the most honest books ever published about a rock and roll star. Ryder bares his heart and soul as he attempts to come to grips with the reasons behind his often self-destructive behavior and the personal carnage often left in its wake.

He also uses his book as a platform to express his still simmering rage at the music industry as a whole and at individuals such as Bob Crewe, Robert Stigwood, and Bud Prager, that screwed him over and damaged his career. Ryder learned much about himself during his journey into the heart of darkness and has emerged triumphant on his own terms as a result. Those who purchase the book also get a free download of Mitch's latest CD, "The Promise", produced by Don Was.

It Was All Right – Mitch Ryder’s Life In Music. By James A. Mitchell, 2008, Wayne State University Press, Detroit Michigan. This book provides the inside story on Mitch’s time with the Detroit Wheels, and it also covers his much longer solo career. There are a number of factual errors in the book, however, that could have been easily corrected before the book went to press. Mitchell obviously needed a fact checker for this project that knew something about Rock and Roll history. Unfortunately, the errors had the effect of spoiling an otherwise compelling story.