Honorary Inductions to MRRL were started in 2008 to give credit to the people behind-the-scenes who were significant contributors to the history of Michigan rock and roll. These include artists, photographers, label owners, publicity directors, music promoters, session musicians, songwriters, and record producers – important people who may not be household names to most Michigan music fans.

Al Abrams was selected to be a Michigan Rock and Roll Legends Honorary Inductee in 2011. Al’s work as the national promotion director for Tamla Records and Jobete Music, and later as director of advertising and public relations for Motown was instrumental in helping the company become one of the most successful record labels in the history of popular music. Past Honorary Inductees from the Motown family include label owner Berry Gordy Jr. in 2009, and the songwriting/production team of Holland-Dozier-Holland in 2010.

Abrams’ efforts benefitted almost all the stellar list of Motown artists who have been inducted into MRRL from 2005 through 2011: Marvin Gaye, the Four Tops, Martha & The Vandellas, Smokey Robinson, Stevie Wonder, the Supremes, the Temptations, Mary Wells, the Miracles, Jr. Walker & The All Stars, the Marvelettes, the Funk Brothers, and Diana Ross.

He also promoted or did publicity for the majority of the Motown recordings that have been voted Legendary Michigan Songs from 2007 through 2011. These include “My Girl”, “Do You Love Me”, “The Tracks Of My Tears”, “Dancing In The Street”, “Money”, “My Guy”, “Baby I Need Your Loving”, “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough”, “Shotgun”, “Please Mr. Postman”, “Heat Wave”, “ Baby Love”, and “I Can’t Help Myself”.

Al, the only child of Harry and Mildred Abrams, was born in Detroit in February of 1941. He was raised in a small Jewish community in a neighborhood in the area of Michigan Avenue and 29th Street. The Abrams family home was a two-family flat that was shared with Mildred’s parents. The house was a straight shot from downtown and Briggs Stadium, the home of the Detroit Tigers, and the Cadillac auto plant.

During the 1940’s it was a bustling, mainly Polish, working-class community with thriving businesses such as the Warsaw Bakery. There was a synagogue on the corner of 29th Street almost kitty-corner from the Crystal Theatre, where young Abrams would attend movies on the weekends, and a number of Jewish-owned businesses on Michigan Avenue including Fogelman Furs, owned by Al’s Uncle Harry Fogelman.

His father, Harry Abrams, owned two large semi-trucks. He was a produce wholesaler of potatoes and onions and would travel throughout Michigan and Ohio buying crops from farmers which he would sell to grocery chains in Detroit. Harry Abrams was one of the first independent truckers to hire an African-American driver. Young Al remembered that when the local motels refused a room, the driver slept on the Abrams’ couch and ate his meals with them.

Abrams’ father died when he was 11, and his mother went to work in the kitchen of a popular restaurant. She and her son were forced to move into homes shared by four families because of their reduced circumstances.

As Abrams was growing up, he became attuned to what were then called “race records”. He used to listen to WLAC out of Nashville, Tennessee, on his tiny transistor radio in bed every night before he went to sleep. Two of the station’s disc jockeys, “Hoss” Allen and “John R” Richbourg, played the rhythm and blues records you couldn’t hear anywhere else on the radio.  Joe Von Battle in his record store

Joe Von Battle in his record store

When he saved enough money, Abrams would take a streetcar to and from black-owned record shops including Joe Von Battle’s on Hastings Street in Detroit’s old Black Bottom neighborhood. There he would buy 78s like “You Tickle Me Baby” by the Royal Jokers and “Gee” by the Crows. If he spent all his money on records, he would walk all the way back home, eager to share his new sounds with his friends. They would often memorize the lyrics and stand on the corner at night and sing a cappella until the people in the apartments started screaming at them from their windows.

By the the age of 14, he was attending Central High School. Abrams went down to the local black newspaper, the now defunct Detroit Tribune, and told them he wanted to be a reporter. They gave him a press card and let him write a column that featured high school news and music gossip called the Central Chatterbox. He was the only white face at the Tribune.

Being a bright student who graduated from high school at 15, Abrams was interested in pursuing a career in labor relations but was too young to attend college. He lied about his age to get a job with the Handleman Company, a distributor of phonograph records to retail operations. Abrams stayed there two years, spending most of his paycheck on records he could get at a discount, before the company discovered his true age and let him go.

He claims that he was influenced by the 1957 film Sweet Smell Of Success to go into the field of press relations. The film starred Burt Lancaster as a ruthless gossip columnist and Tony Curtis as a press agent who would do just about anything to curry his favor. In Abrams’ mind, the film portrayed the glamorous lifestyle of the profession, and his knowledge of what the job entailed initially came from that movie.  Devora and Jack Brown of Fortune Records

Devora and Jack Brown of Fortune Records

Again lying about his age, Abrams got a job in the mailroom of an advertising agency in Detroit. But he had been bitten by the music bug, and he kept looking for opportunities in the field he loved. He frequently dropped by to see Jack and Devora Brown at their Fortune Records studio and store on Third Avenue and tried to convince them to hire him as a promotion man for the label. Worn down by his pestering, the Browns finally relented and gave Abrams a business card that he proudly filled out with his name and the “Promotions” title. He was only given one copy of “Jail Bait” by Andre Williams to promote; but he was soon to make a contact that would end his brief relationship with Fortune Records and set the course for the rest of his life.

In an extensive interview for the Living Music project of the University of Michigan with a young high school student named Dylan Morris, conducted under the tutelage of Dr. Mark Clague, Al Abrams related the story of how he came to be hired at Motown. In 1959, Abrams looked into taking a job for $15 a week to drive artists to record hops. This was a form of payola whereby record promoters supplied artists to perform for the DJs in the hope they would get airplay. This led him to a job interview at a residence at 1719 Gladstone where Berry Gordy Jr. and Raynoma Liles were living. They had formed a business called the Rayber Music Writing Company whereby for $100 they would make a recording of an aspiring artist and press it onto a vinyl record.  Berry Gordy Jr. and Raynoma Lyles

Berry Gordy Jr. and Raynoma Lyles

Abrams interviewed with Berry Gordy for the job. Not really interested in hiring someone so young, Gordy gave Abrams a record called “Teenage Sweetheart” by a Yugoslavian immigrant who recorded it under the name Mike Powers with dreams of becoming a singing idol. Gordy told Abrams he could have the job if he could get the record on the air. The song was awful, and Gordy thought Abrams would never get it played.

The next day (Memorial Day) Abrams took the record to a remote broadcast being done by Larry Dixon of WCHB out of Inkster, Michigan. He badgered Dixon for nearly four hours out in the heat to play “Teenage Sweetheart”. Finally, the only way Dixon could get rid of him was to play the record. Unbeknownst to Abrams, Gordy and Liles happened to be driving on Belle Isle, a park located on the Detroit River, listening to WCHB when the song came on the radio. Gordy reportedly almost lost control of the car and said, “Oh my God, the white kid got the record played. Now we’re going to have to give him a job.”

Abrams agreed to start work for $15 a week and all the chili he could eat. It was prepared by a woman employee named Lillie Hart who was taking care of Gordy and Liles’ child and cooking as well. After the move to 2648 West Grand Boulevard, she later cooked daily hot lunches for all the employees and artists at Hitsville. Abrams was named national promotion director of tiny Tamla Records and Jobete Music Company, which Gordy had just started.

Young Abrams pulled off his share of outrageous PR stunts in his new position. A memorable one involved him wearing a turban, fake beard, and white sheet while visiting Detroit DJs to promote a two-part instrumental on Tamla called "Snake Walk" by the Swinging Tigers. Abrams also brought along a snake charmer's basket and a large rubber snake to add to the fun. Abrams promoting "Snake Walk"

Abrams promoting "Snake Walk"

Besides promoting recordings at local radio stations, his responsibilities soon included writing the first Jobete and Tamla advertisements for Billboard, Cashbox, and other music business publications. Abrams couldn’t type, so he wrote the releases on a legal pad. In the days before copying machines, he would take around handwritten material to media outlets. On a trip to New York he took one to the legendary Walter Winchell. Winchell grabbed the sheet of paper out of Abrams hand, and he told him that he had to sit down and type it out. Abrams typed it in Winchell’s office with one finger, a technique he still employs today.

Abrams wrote all of the artist bios for the label as well as liner notes for albums. Some of what he wrote looks pretty hokey today. If one looks at the back of the Marvelettes’ first album, “Please Mr. Postman”, there’s a personal letter to the fans that was supposed to be written by the group. Apparently very few of the fans noticed “liner notes by Al Abrams” printed at the bottom.

He also came up with a variety of memorable phrases to promote Motown. He had no formal training, but along the way he produced a few legends. The most memorable of these was “The Sound Of Young America.”

When Motown started in 1959, the strategy was to get stories into the black press to create hype about the black artists on the company’s roster. Since Motown was a fledgling company with only regional appeal, Abrams’ early public relations work was directed toward an African-American audience. He learned what to do from a variety of professionals in the business, so that by the time the company had grown to the point that it was ready to go to the larger white audience, he had the know-how to approach major publications like Time and Newsweek.

In the early days, Abrams used to travel with the Miracles, Barrett Strong, and even served as road manager for a brief period for Motown’s legendary doo wop group, the Satintones. The first big public relations break for the Tamla label involved the Miracles. The group used to travel in an old Volkswagen bus. There were so many fans in the street for their appearance in St. Louis that their vehicle couldn’t get through when they arrived at the venue. The police had to come to the scene and Abrams called Gordy in Detroit to tell him about the incident. Gordy asked if Abrams could get the story into JET (a weekly magazine targeted toward African Americans). Abrams not only got it into JET but also the Michigan Chronicle. Because the label’s early publicity was directed toward the black media, the Michigan Chronicle and the Detroit edition of the Pittsburgh Courier were very important newspaper contacts for Abrams and Motown at that time.

This aspect of his job quickly became his favorite endeavor, and Abrams gradually moved away from record promotion to concentrate his efforts on publicity and press relations for Motown.

His first big breakthrough in the mainstream white media was the Detroit Free Press. Mort Persky was the Sunday editor, and Abrams could usually rely on him to recognize the value of and print any worthwhile story on Motown and/or one of its artists. Once Motown got rolling in the early 60’s, the label and its artists became hometown heroes. They were adopted by the Free Press, and Abrams was placing 5 to 7 stories a week in the paper. Many appeared in the Detroit Free Press Sunday edition’s Detroit Magazine. To reciprocate, Berry Gordy always made sure that the local media was taken care of. When the Free Press started a teen page, Motown had Marvin Gaye record a commercial for free.  Abrams and Eddie Holland

Abrams and Eddie Holland

Abrams worked for the most part singlehandedly. He didn’t trust anyone else to do the job that he knew he could do. He came up with a variety of interesting ways to promote the label, including using CKLW-TV movie host Bill Kennedy. Abrams would bring Motown stars like Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, or the Supremes to appear live on the program. In another early promotion, Abrams took two of the label’s artists, Marv Johnson and Eddie Holland, down to Hot Sam’s clothing store and made a trade. If the store gave them suits, they would plug Hot Sam’s when they went on TV wearing them.

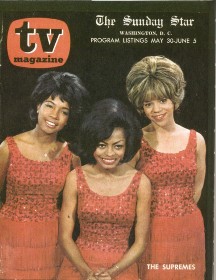

The newspaper that he had a lot of trouble cracking was the Detroit News. Abrams revealed in the Living Music interview how he finally managed to achieve it. After the Supremes had notched their third # 1 hit, it was driving Abrams crazy that he couldn’t get them on the cover of the TV magazine that the paper put out. Finally, Abrams went to see the features editor at the Detroit News. The editor pulled him aside and said, “I gotta ask you – what’s a nice Jewish boy like you doing working for a bunch of niggers like them? Shouldn’t it be the other way around?” Abrams had been waiting for some kind of racial slam so he replied, “Well let me tell you the truth: you know how these black people like to play dice? Well, I really started Motown Records, and one night I got into a craps game with Berry Gordy, and I lost the whole thing. But they let me stay on and do the publicity anyway.”  Supremes TV Magazine cover

Supremes TV Magazine cover

The editor bought the story completely and said, “That’s the saddest story I ever heard.” Then he told his staff, “From now on, I want you to do whatever you can to help this guy.” As a result of Abrams’ tall tale, the Supremes became the first African-Americans to be on the cover of a TV magazine.

Abrams stated that a year later the Detroit News did a big story about Motown and that same editor wanted to meet Berry Gordy. Abrams arranged it, and the editor arrived at Gordy’s Hitsville office in a chauffeured limousine. At the meeting he said to Gordy, “I’ve wanted to meet you. You know, my maid listens to your music all the time.” Abrams claimed that Gordy enjoyed the attention of the white media, but racially insensitive remarks like that one must have made him shake his head.

In the early days of the label in 1959 and 1960, Abrams was primarily involved in getting airplay for Motown releases. The technique he commonly used in Detroit was to buy some high quality liquor and bring it to a station like WCHB along with a new recording by a Motown artist. He would walk right into the studio, give the disc jockey the bottle, and Abrams would put the record on the DJ’s turntable and the DJ would play it on the air.

When Abrams traveled to New York with a copy of Barrett Strong’s single, “Money”, to try to get famed DJ Alan Freed to play it on WABC, he had to use a different approach. The benches outside the studio were filled with promotion agents, so when Abrams got in, he gave Freed the record and $100. This was Freed’s “consulting fee” for giving his opinion of the record’s merits. The practice had its consequences, however. Soon after, Alan Freed became one of the first disc jockeys to be indicted for payola.

In another instance, Abrams compensated DJ Chuck Daugherty for helping to break Barrett Strong’s “Money” on WXYZ in Detroit by recruiting Motown’s young black songwriting and production team of Holland-Dozier-Holland to help Daugherty move. After they had packed and moved him, all of them decided to take a break. The five of them went to a restaurant in Farmington, but they refused to serve Brian and Eddie Holland, or Lamont Dozier. Abrams had to buy carry-out hamburgers for Motown’s soon-to-be millionaire songwriters.

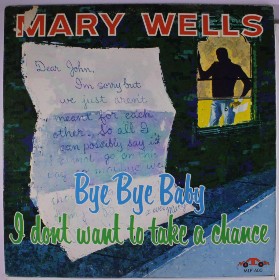

In the days prior to the Civil Rights legislation Abrams sometimes had to walk a fine line in regards to publicizing Motown’s roster. A decision was made on both the Marvelettes’ “Please Mr. Postman” and Mary Wells’ “Bye Bye Baby” albums not to put their pictures on the cover. Instead, cartoonish representations were produced for the respective covers; a mailbox with a spider web for the “Please Mr. Postman” L.P. and a ‘Dear John’ letter, written by Abrams, for the “Bye Bye Baby” album.

Abrams claims that the company did not want to over-promote the blackness of its artists. Motown figured everybody knew about it anyway, but the emphasis was to try to get into the white market without boldly announcing that they were black.

Another factor in these decisions was Gordy’s belief that most record stores at that time would not prominently display albums that featured pictures of black artists. As a result, the covers of the “Greatest Hits” collections issued for Motown artists in the 60’s showcased the song titles rather than photographs of those who sang the hits.

Despite the growing appreciation of Motown artists and their songs, black and white audiences were segregated on the early Motortown Revue tours in the South. In theatres, one group would be seated in the balcony and the other in the floor seats. In auditoriums, the color barrier was enforced by a rope that divided the dance floor.

The racial prejudice faced by Motown artists was common in both the North and South. Abrams recalls staying in a hotel in Chicago for a show Smokey Robinson was doing with The Miracles. Robinson came to pick Abrams up and Abrams got a knock on the door – it was the hotel manager. He said, “I’m sorry sir, you’re going to have to leave the hotel – you can’t have any colored guests.” Abrams checked out and went to stay in Smokey’s hotel. He claims to have never stayed in a whites-only hotel again. He had more fun staying with Berry Gordy and the Motown artists.

Abrams told the Living Music interviewer that he and Gordy were like brothers in the early days, and like an older sibling, Gordy would often give Abrams clothing from his own wardrobe. Abrams claimed that Gordy even learned Yiddish, just to communicate with his mother.

The pair had a lot of fun together. One example occurred in Washington D.C. Abrams and Gordy wanted to see the movie Ben-Hur, but at that time the theatres in Washington were segregated. Abrams knew about the African diplomat exemption, so he had Gordy speak African gibberish at the box office. Abrams then explained that Gordy was an African diplomat, and they got in to see the movie together.  Abrams co-wrote Marv Johnson's hit

Abrams co-wrote Marv Johnson's hit

In another instance, Abrams was in the backseat of a car with Gordy and Robert Bateman coming back into the United States from Canada through the Detroit-Windsor tunnel. John O’Den and Raynoma Liles’ brother Mike Ossman were in the front seat. They along with Abrams and Gordy had just written a song for Marv Johnson called “I Love The Way You Love”. It would earn a gold record for Johnson in 1960. (“I Love The Way You Love” was the only hit song Al Abrams would ever have a part in writing.) The customs officer on the U.S. side asked the pair in front who they were, and then shined his flashlight in the back and asked, “Who do we have here in back?” Gordy answered, “Ain’t nobody here but us niggers.” The agent looked at Abrams and seemed to be thinking, “Wait a minute, did I hear that right?” Then he just shook his head and walked away. The bond between Al Abrams and Berry Gordy was, like white on rice or black on coal, as close as close can be.

That closeness even extended to Motown business meetings. Abrams has said that they always started them by singing a song called “Hitsville U.S.A.”, with an opening line of “Oh, we are a swinging company here at Hitsville U.S.A.”. Everyone was expected to sing it, and if Gordy thought you were faking the lyrics, he would choose that person to lead the song. This approach was never taught in business school, but it helped keep the family feeling in the organization.

The same family feeling existed between Motown and the city of Detroit. There was a love affair between the label and the city. Part of it was due to the accessibility of Hitsville U.S.A., its artists, and Gordy himself; and the other was the pride the city took in the incredible success that Motown enjoyed. Jerry Cavanagh, the mayor of Detroit and George Romney, the Governor of Michigan would both appear with Motown artists such as the Supremes at the Michigan State Fair or other events, basking in the glow and reaching out to touch and be part of the Motown phenomenon.

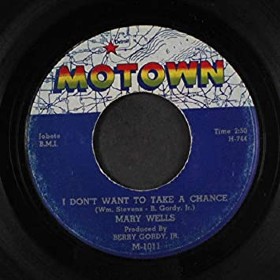

Berry Gordy’s initial releases had been issued of the Tamla label. He first launched the Motown record label in the fall of 1959 for the Miracles’ second single, “Bad Girl”. The Motown name was a hip reference to Detroit’s nickname of the Motor City. The Motown label was originally pink with black lettering, and Abrams remembers that there was some reluctance to switch to the now-famous blue logo with the map of Detroit. There was worry that putting the city’s name on the label might backfire.

The map label was first issued on Mary Wells’ second single, “I Don’t Want To Take A Chance”, issued in July of 1961. The new label, showing a map of southeast Michigan with “Detroit” in large print and marked with a large red star, was an immediate hit and a source of great pride for the people of Detroit.  First single using the Motown map label

First single using the Motown map label

Another reason for the warmness and acceptance the city exhibited towards the company was the way Motown gave back to Detroit. There were a lot of free appearances in the community that were never mentioned in the press because they weren’t done for publicity. Motown and Berry Gordy were also very generous and ready to help friends and others in need. These things, along with the endless stream of hit records being churned out of the famed Studio A on West Grand Boulevard, led to what Abrams has described as “Motown and Detroit becoming almost synonymous.”

This was undoubtedly helped by the media; especially television, the disk jockeys, the Free Press, and eventually the News. It was unparalleled the way the city embraced the label and how everyone wanted to play a part in it. This is the area where Abrams played such a big role in the label’s success. His public relations work helped make Motown something that Detroit could be proud of, and Motown, in return, had a great deal of pride in the city.

Serendipity played a role as well. The timing was perfect as Motown’s ascendency came at the same time as the incredible success of the Beatles and the British Invasion. The Beatles said some very complimentary things about Motown; and they, along with the Dave Clark Five and the Rolling Stones, covered the label’s songs, giving Motown artists instant hipness and credibility with white teens and increased airplay on all the white radio stations.

Once Motown started to become a household name with nationally famous stars the company made a decision to concentrate more on white America. The focus of Abrams’ job became feature stories. Abrams did a lot of ghostwriting for stories that appeared in teen magazines and were purported to have been written by Diana Ross, Mary Wilson, or Florence Ballard. Abrams says that the type of things he was writing could be described as basically public relations hype, but in that more innocent time the fans of the Supremes, the Four Tops, and fans of Smokey and the Miracles took it as the gospel truth.

Gradually the stories he produced took more of a Hollywood slant – publicizing shows at the Copacabana, promoting appearances of Motown stars in movies or on network television, meeting established stars like Judy Garland, or hyping European tours. Although this type of material was directed at the national white media, Abrams claims that he always kept the black publications in the loop.

Motown also started signing people for PR purposes. Las Vegas-styled artists like Billy Eckstine and Tony Martin had great talent and reputations but they were not going to revitalize their careers with a Holland-Dozier-Holland song. The label even tried to sign one of Lyndon Johnson’s daughters. None of these types of signings ever produced a hit; and although they generated a good deal of publicity for Motown among white audiences, they also represented the beginnings of a move away from the company’s roots and the dynamics that had made it great.

By the end of 1966, Abrams began to suffer what he described as a bout of Jewish self-doubt. He asked himself whether all the PR success Motown and its artists enjoyed was a direct result of his efforts, or if anyone could have done it given the extraordinary amount of talent and genius at the label.

There was also the issue that Abrams was earning less at Motown than others working in public relations in the entertainment industry. He almost left the label to take a job as a publicist for United Artists to work on the James Bond films; and although Berry Gordy gave him a raise for staying at Motown, Abrams’ days at the company were drawing to a close.

In November of 1966, Abrams was contacted by New Worlds Inc., the public relations firm that was promoting a Dick Clark show at the Michigan State Fair Grounds starring Gary Lewis and The Playboys, The Yardbirds, and Sam The Sham and The Pharaohs. The PR guys were looking for a gimmick and hired Abrams because of his many successful promotions at Motown.  Abrams' Mod Wedding promotion featured Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground

Abrams' Mod Wedding promotion featured Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground

Abrams came up a concept called the Carnaby Street Fun Fair which would highlight the world’s first Mod Wedding. The bridal couple (Randi Rossi and Gary Norris) was found through the Detroit Free Press Action Line. The pair earned the chance to exchange their vows in the highly publicized ceremony after the original couple, who had won the wedding competition on the popular Detroit radio station WKNR, had to withdraw.

To insure maximum press coverage for the event, Abrams contacted Andy Warhol to stage a “happening” at the Fun Fair for $1,500. That brought Warhol’s traveling music, film, and light show extravaganza called the Exploding Plastic Inevitable to Detroit, including the rock and roll music of the Velvet Underground with Lou Reed and Nico.

The highlight of the affair, which was covered in newspapers around the world, had Warhol giving away the bride, attired in a specially designed mini-skirt wedding dress set off by thigh-high boots. Other press-worthy stunts included a member of the Warhol crew smashing a car with a sledge hammer as a statement about Detroit, and Warhol applying paint and ketchup to a woman’s paper dress while she was wearing it.

Two weeks later on December 7, 1966, Abrams was fired from Motown by Michael Roshkind, one of the new white executives brought in by Berry Gordy as the company expanded. Abrams had angered Gordy by questioning Roshkind’s credentials, and that led to his dismissal. Because of his close relationship with Gordy, he was offered the same deal as several Gordy family members who were put out to pasture. He could remain on the Motown payroll indefinitely if he did not speak to the media, only coming to the office every two weeks to pick up his paycheck.

Abrams stayed on through the Christmas holidays and then joined New Worlds, Inc. Early in 1967, he resigned from that company and founded his own public relations firm, Al Abrams Associates. His first clients were Ollie McLaughlin’s Ann Arbor-based Karen and Carla Records, Florence Ballard, and the popular Stax/Volt label out of Memphis.

In 1969, Abrams began working with Holland-Dozier-Holland’s Invictus/Hot Wax labels, first through their attorney in their lawsuit against Motown, and then as PR Director. He continued working as a music publicist for a variety of clients, including James Brown, until he switched the focus of his agency to representing non-music clients such as the Perry Drug Store chain, new home builders, and political candidates.

Abrams kept his hand in the music business, however, and in 1972 he wrote the first-ever press biography for Bob Seger after he recorded his "Smokin' OP's" album for Punch Andrew's Palladium label. He also settled his differences with Michael Roshkind at Motown and did some well-paying but off-the-books assignments for the label.  Abrams at Motown's 50th

Abrams at Motown's 50th

By this time, Motown had abandoned Detroit and moved its headquarters to Los Angeles. Many people felt betrayed when the company that was so closely associated with the Motor City left it behind. Although Motown would go on to sell millions of records in California and achieve some success in motion pictures, the move would prove to be a mistake. Straying from its roots, the label would no longer be the force in black music that it was in the 60's.

In 1974, Abrams joined Gale Research, then North America's third-largest publisher of reference books, as their PR Director. He was promoted to editor of their Journalism Department in 1976; and the company published the first three of his books.

Abrams went on to open Gale's Great White Bureau in Canada in 1981, and he lived in Toronto and Windsor while holding "landed immigrant" status. He also started writing for newspapers and magazines including the Windsor Star, Detroit Free Press, and the Toronto Globe and Mail, before joining the Windsor Star as a reporter in 1985.

Abrams returned to the US in 1990 and worked as a gossip columnist and book page editor through 1994 before going back to free-lance writing. He was also employed as a publicist for major global and industrial clients and for a start-up computer storage application in Isreal.

Memories of Motown, a musical that he co-wrote and appeared in with his old Motown colleague William "Mickey" Stevenson, debuted in Berlin in 2009 to coincide with Motown's 50th anniversary. A downsized version is scheduled to be performed with the Reno (Nevada) Philharmonic in May 2012.

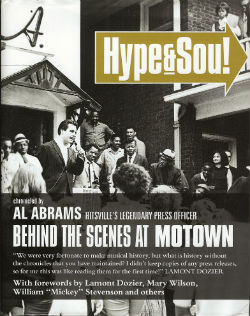

Al Abrams was inducted into the MRRL Hall of Fame in June 2011; and his memoirs, Hype & Soul: Behind The Scenes At Motown was published in the UK in September 2011 by Temple$treet Publishers. It is the twelfth book Abrams has written during his remarkable career.

Sadly, Al Abrams passed away from cancer in 2015 at the age of 74 at his home in Findlay, Ohio. Motown Black & White, an impressive collection of Abram's Motown materials, is currently being exhibited around the world in his memory.

Dr. J.Recommends:

"Hitsville USA - The Motown Singles Collection 1959 - 1971" 4 CDs. This incredible collection of songs covers the years that Al Abrams worked for the label and Motown was headquartered in Detroit. Anyone serious about collecting the music of the Motor City's greatest label should start here.

On The Bookshelf:

Hype & Soul: Behind The Scenes At Motown by Al Abrams. TempleStreet Publishers UK, 2011. A very unique and interesting look at the most successful black-owned record label in history. There have been many books written about Motown and its great artists, but there is nothing out there quite like Hype & Soul.

Al Abrams was there at the beginning, and he shares his vintage press releases, unpublished photos, and some great stories of his days and nights with Motown. This is an absolute treat for the eyes, and a must-read for any fan of popular music.