Harry Balk was one of the early movers and shakers of the Detroit music scene as a manager, record producer, and label owner. His first important contribution was the discovery of Little Willie John, and, as his manager, guided the young singer through his early R&B recordings, including the # 1 hit "Fever". Balk went on to establish the Twirl, Impact, and Inferno record labels, and he discovered a number of other important artists including Johnny and The Hurricanes, the Shades of Blue, and Sixto Rodriguez. After forming Embee Productions, Balk enjoyed his greatest success as the co-producer of "Runaway" and the other early recordings of Del Shannon. In the late 1960s, he became the head of A&R at Motown Records and was influential in establishing its Rare Earth subsidiary label.

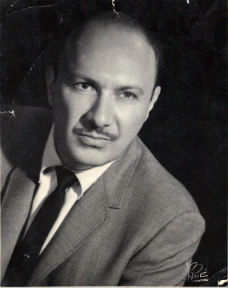

Balk was born October 1, 1925, in Detroit, Michigan to Lena "Leah" and Max Balk, Russian Jewish immigrants. Harry's older brother died at birth, so to his mother thought he was a miracle and, because he was the only boy in the family, she and Harry's three younger sisters showered him with affection. His grandparents lived right across the street, and his grandmother's great love for her only grandson was something he spoke about often.*  Harry Balk

Harry Balk

His father Max was sick most of Harry's life so Leah had to support the family, working several jobs at a time, barely making ends meet. Harry grew tired of watching his mother suffer and, as soon as he was able to get a driver's license, he dropped out of school and went to work. He sold shoes and appliances in a department store.*

Balk wasn't challenged by his sales jobs, however, nor was he satisfied with the money he was making. He was a skilled pool player, and his real love was hustling in the pool halls. The more money he made, the more he did it. But when he would come home with a little too much cash in his pocket, his mother knew he'd been hustling, and her disappointment was something Harry couldn't handle. She was the judge and jury of his success and failure in life. Balk relied on her wisdom and he inherited her faith. Leah's belief in God was the basis of her life, and her love and faith in Judaism was something Harry emulated all his life.*

Harry Balk was also a ladies man, and he loved to hang out in the jazz clubs in the black neighborhood where he lived. According to his granddaughter, Laura, he embraced the culture to the point where if you closed your eyes while he was talking, you'd swear he was black. Not only his talk, but his walk and his mannerisms made the black men in his neighborhood call him "a brother turned inside out."*

Balk's uncle owned several movie houses. Balk had grown up in the projection booth running the movies for his uncle, and he became an expert - able to quickly fix any film issue that came up. These technical skills would help him later when he started producing songs. At the age of 30, Balk purchased one of his uncle's theaters that was located in a predominantly black area of Detroit. *

By the mid-1950s, however, television had become the major factor in the decline in motion picture admissions across the country. In order to bring in more business to his theater on slow nights, Balk was approached by local promoter Homer Jones with the idea of holding amateur talent shows at the venue on Tuesday and Thursday nights. They were an immediate hit with lines around the block on the nights the talent shows were held.

A young singer named William Edgar John seemed to win every contest, and his successes gave Balk the idea that he might be able to make some money in the music business. John had moved to Detroit at a young age and had been performing with other family members, including his sister Mable, in a gospel quartet called the United Four.**

Balk signed the teenager to a six-year management contract and was able to get the singer a recording contract in 1955 with Syd Nathan's King Records in Cincinnati, one of America's leading independent record labels. Nicknamed Little Willie John because of his short stature, the 18-year-old made an immediate impact with his first release, "All Around The World", which reached # 5 on the Billboard R&B chart in late 1955.

Balk was in the studio during the recording of Willie's "All Around The World" with producer Henry Glover. Balk watched Glover closely and decided that he could do what the producer was doing. In fact, he gave Glover advice during that first session. "I said, the sax should be doing this and that and they all looked at me like I was crazy," Balk told an interviewer, "but a few minutes later Henry would say, 'have the sax do this or that', and the next time Willie was supposed to go in the studio he told the head of King Records to make sure that his manager is with him."*

Little Willie John emerged as a major R&B artist in 1956 with his next release, "Need Your Love So Bad". The single reached # 5 on the R&B chart and its flipside, "Home At Last", also charted at # 6. His biggest hit in 1956, however, was "Fever". The single was released in April of 1956 and spent three weeks at # 1 on the R&B chart. In addition, it became Little Willie John's first record to cross over to the pop charts when it peaked at # 24 on Billboard's Hot 100. It also became Willie's second two-sided smash when its flipside, "Letter To My Darling", became a # 10 R&B hit.

Despite all his chart success, which included 1958's big hit ballad "Talk To Me", Little Willie John's short temper, along with his propensity to abuse alcohol and wave his gun around, made his manager's life difficult. In a 1999 interview with John Rhys, Harry Balk recalled his time with the volatile young singer: "Willie was kind of a problem child on the road, always shooting up the hotel rooms." Tired of dealing with all the drama, Balk cut his ties with Little Willie John despite having three years left on his six-year contract.**

Balk also managed Kenny Martin, another Detroiter who recorded sides on Syd Nathan's Federal label. Martin had a Top 20 hit on the R&B chart in late 1958 with the pleading ballad "I'm Sorry". Balk had become more interested in the recording process and, back in Detroit, he gained some valuable experience running some sessions at Fortune Records.**  Balk producing a session

Balk producing a session

According to author David A Carson, Balk joined in a partnership in 1958 with Irving Micahnik, a former furrier with no musical background. The two formed a booking and management company called Artists Inc. While Harry focused on the talent, Micahnik kept track of the money. Described as "cool and upbeat, with a porkpie hat and an ever-present long, thin cigar in his mouth," Balk fit the image of a "boppin'" fifties record man.**

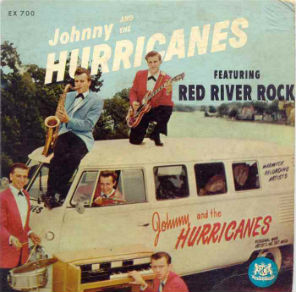

The Orbits were an instrumental band that had become popular playing sock hops and local dances in Toledo, Ohio. They traveled to Detroit to be interviewed by Balk and Micahnik at their offices at 20 Alexandrine, just west of Woodward. The two men signed the band to a long-term contract, and Balk renamed them Johnny and the Hurricanes. Johnny Paris's wailing saxophone over a rocking organ beat gave the group its trademark sound.**

For just sixty dollars, Balk produced the group's first record, "Crossfire", in Stuart Gorelick's small studio inside the Carman Towers Theater on Schafer Road in Dearborn, and he used the vacant cinema to provide echo on the recording. Balk and Micahnik then drove in a beat up car to New York to try to sell the song. They went to every big record company but they all turned them down. Instead of giving up, Harry turned to Irving and said, "How much do you think it costs to put a record out?" After discovering that it cost less than two hundred dollars, Irving and Harry got the money together, pressed the record, and put it out on their own Twirl label. Harry had built up good relationships with Detroit DJ's because of Little Willie John, and he was able to get airplay on several Motor City stations.*

After the record took off, the same people who had turned them down in New York were now approaching them for a deal, but Micahnik came up with a great idea. Instead of selling the song, they leased the master recording for a limited time to Morty Craft, who had just formed Warwick Records. By using this approach, their record could be distributed across the country and, after a period of time, the rights would revert back to Micahnik and Balk. This way they retained control over the masters. "Crossfire" became a national hit, reaching # 23 on the Billboard Hot 100 in June 1959.*

Balk and Micahnik then formed EmBee Productions, and the arrangement they made with Warwick Records made them Michigan's first successful independent record producers. They were also the first company to manage the acts, write the songs, produce the sessions, and own the copyrights to their master recordings. In a later interview, Harry said the only thing Irving refused to do was buy a studio to record the songs. He preferred to go to New York to Bell Sound studios to record so they could be around all of the big music talent that recorded there.*

In no time, Balk had Johnny and the Hurricanes in Bell Sound to record a follow-up. During a break in the session, Balk heard the organ player fiddling around with a note. Harry called out to the musician, "Do it again, play that again." The notes came together and formed "Red River Rock", a revved up version of the old western song "Red River Valley". Leased to Warwick, it became a smash, going to # 5 in Billboard and making Johnny and the Hurricanes one of the best-known instrumental bands of the era.**

On the composition side, Micahnik, who had gone to law school but never practiced law, had the idea to record out-of-copyright songs like "Red River Valley" so they could own the publishing and also receive writing credit using pseudonyms. They formed two publishing companies, one named Amy Music, after Micahnik's daughter, and Vicki Music, after Balk's daughter. They then proceeded to take writing credits with Micahnik listed as 'Ira Mack' and Balk as 'Tom King'. The pair continued to do this on other hits by Johnny and the Hurricanes culled from the public domain, such as "Reveille Rock" and "Beatnik Fly".*

According to Balk, the musicians were receiving a 6 percent royalty rate on sales of their records. At the same time, however, Johnny and the Hurricanes were paying 15 percent to their New York booking agent and 20 percent to Balk and Micahnik. In addition, hotel, transportation, and other expenses were deducted from their earnings. There were some EmBee artists who complained about unfair contracts, low percentages, and missed royalty payments. In an interview with John Rhys, Balk stated that many times he and Micahnik had their own problems when trying to collect money from distributors. "Most artists of the day were okay when they signed," Balk said, "but after getting a hit, they wanted out."***

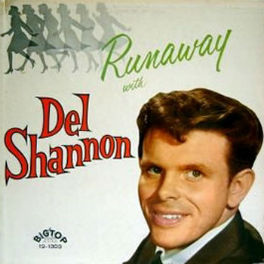

In 1960, Micahnik and Balk cut loose Warwick and Morty Craft to sign a new pact with Johnny and Freddy Bienstock, executives at Big Top Records. Big Top was owned by the Aberbach brothers, Jean and Julian, who also owned the massive Hill & Range Publishing arm. Johnny and the Hurricanes were huge at this time, and Balk and Micahnik added several new acts to their stable including Liza Smith, Mike Drummond, the Five Teenbeats and most importantly, in the summer of 1960, Del Shannon and Max Crook.**

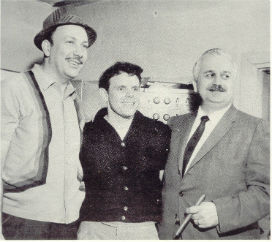

"We never had to really search out acts." Balk explained, "We got a lot of foot traffic to our door. If we liked them, we signed them, and if not, Hit the door!" Ollie McLaughlin, who was a deejay in Ann Arbor, brought in Del Shannon and Max Crook. "Ollie and Max were friends and that's how we signed Del," Balk recalled.**  (L-R) Max Crook, Ollie McLaughlin, Del Shannon

(L-R) Max Crook, Ollie McLaughlin, Del Shannon

Del Shannon's real name was Charles Westover, and he was born on December 30, 1934. He grew up in the West Michigan farming community of Coopersville. At fourteen, he took up the guitar and started performing at local school shows. After graduating from high school, he was drafted, got married, and by 1960 was selling carpets during the day and fronting a band at a rough and tumble Battle Creek bar at night.

After changing his name to Del Shannon, he formed a partnership with the band's keyboard player, Max Crook, and they began writing songs and recording demos with the hope of getting a record deal. Crook knew popular Ann Arbor disc jockey Ollie McLaughlin and convinced him to drive to Battle Creek to see Shannon and the band perform. McLaughlin made a tape of the performance and brought it to Balk and Micahnik in Detroit. Not only did they like Shannon, but Balk was also intrigued by the sound Crook made on a high-pitched, custom-built keyboard instrument he had created called a 'musitron'.

Both Shannon and Crook were signed to contracts, but it took until 1961 for the pair to come up with a song called "Runaway" that Balk thought had hit potential. He booked a session at Bell Sound in New York but Balk was unhappy with Shannon's vocal. Balk sent them back for a second session, but again Shannon's vocal was too flat to satisfy Balk. An engineer in the studio fixed things when he sped up Shannon's vocal to get him on key, and "Runaway" was issued on Big Top in March 1961.

The song, with its distinctive musitron solo, was a gigantic hit, spending four weeks at # 1 on the Hot 100 and earning Billboard's Song of the Year honor for 1961. "Runaway" made Shannon an instant star. He appeared on American Bandstand; and his bio was written by Irving Micahnik, who changed the married 26-year-old singer with two kids into a 21-year-old milk drinking superstar, unmarried and available to all young women. When wife Shirley traveled with Shannon on tour, she was billed as his sister.*

Del Shannon followed it up with three more Top 40 hits on Big Top in 1961: "Hats Off To Larry", "So Long Baby", and "Hey! Little Girl". Micahnik set up the same deal with Shannon's recordings that he had done earlier with those of Johnny and the Hurricanes. After a certain period of time, Big Top returned the masters of the recordings and 100% of the publishing to EmBee Productions.

By 1962, Johnny & The Hurricanes' hits were drying up. Del Shannon's hits had tapered a bit as well, but he continued to crank out Top 40 hits for the Twirl stable under the Big Top banner well into 1963. Shannon was especially popular in England where he had Top 10 hits with "The Swiss Maid", "Little Town Flirt", and "Two Kinds Of Teardrops".

Twirl struck gold in 1962 with the duo of Don & Juan when "What's Your Name" climbed into the Top 10 as a Big Top release. They also had a sizeable hit with "Misery" by the Dynamics in 1963. "Leasing records to major labels minimized our risks," Balk recalled. "They would take a cut, of course, but their distribution systems were far superior to what we could pull off having released on Twirl alone. Irving managed most of the live booking gigs for the acts," Balk explained, "and he managed to do a pretty good job of keeping the acts on the road and on tour, especially when they had a hit record. Sometimes he traveled with them overseas, such was the case with Del Shannon on European and Australasian tours."****

In August of 1962, Balk and Micahnik attempted to take Twirl to bigger heights by issuing more recordings on their own label. Included on their "2000" numbered series were the Young Sisters, Patti Jerome, Maximilian (Max Crook), Grant Higgins, the Four Imperials, Ronnie Putirka, Eddie Reid, Vivian Jones, and the Royaltones.****

By late 1963, however, things got ugly. Irving Michanik, who allegedly was a habitual gambler, had many unpaid debts in New York and Detroit, including unpaid recording time. Recording studios Bell Sound and Mirasound were pressuring Big Top Records for payment. In the end, Johnny Bienstock paid the outstanding bill but, as a result, severed ties altogether and denied Irving access to the masters.****  Balk, Shannon, Micahnik

Balk, Shannon, Micahnik

Del Shannon broke free from the Twirl stable at this time because royalties that were due were not being paid out to him. In retaliation, Micahnik attempted to blackball Shannon in the industry, threatening lawsuits against anyone who would sign him. Del's response was to form his own label, BerLee Records, and he took Twirl Records to court. Fires were eventually put out after Shannon's BerLee sales failed and all parties realized everyone was a loser in the break up. Matters were settled, and Shannon came back to Twirl in early '64, with his subsequent recordings being leased to Amy Records, a subsidiary of Bell Records.****

The Royaltones were playing on most of EmBee Productions at this point. The band's lineup had changed and now included guitarist Dennis Coffey and bassist Bob Babbitt, who would both later become part of Motown's Funk Brothers. They played on Del Shannon's "Handy Man", "Do You Wanna Dance?", "Keep Searchin' (We'll Follow The Sun)", and "Stranger In Town", all released on the Amy label.

By the end of 1965, Irving Micahnik and Harry Balk decided to part ways. As Harry put it, "In the end, nobody was getting paid, and I wasn't getting my royalties either. Things were bad, so I sold out my share of Vicki Music and interests in Twirl Records to Irving for a lump sum, and we parted ways."****  Balk and second wife Patti Jerome

Balk and second wife Patti Jerome

Harry formed a new label, Impact Records, and a new publishing company called Gomba. He took in John Rhys as a junior partner, and they scored a Top 10 hit in "Oh How Happy" by The Shades of Blue. He retained some of the Twirl groups for the Impact label including the Volumes, elements of the Royaltones, Mickey Denton, and Patti Jerome. He also signed new talent that included Sixto Rodriguez (billed as 'Rod Rodriguez'), the Human Beings, the Lollipops, and a folk-rock band from Bay City called the Shepherds that was incorrectly listed as the 'Sheppards' on their only Impact single.

After the split, Irving Micahnik moved the Twirl label to New York. By the summer of 1966, however, Irving was shut down by the Internal Revenue Service and did some jail time for tax evasion. Once released, he went on to manage Chubby Checker, but died suddenly in 1977 of a heart attack.*****

Although Balk and Micahnik's Twirl label had a lifespan of about seven years, it was significant in that it preceded Motown by a few months. It had a major impact with its roots as well, beginning with "race records" a la Little Willie John and Kenny Martin, to early rock 'n roll with Johnny and the Hurricanes, which paved the way to West Coast surf music. Their recordings with Del Shannon also served to bridge the gap in the period following Buddy Holly's death to the British Invasion. In addition, acts like the Volumes, Don & Juan, the Dynamics, and Bobbie Smith & The Dream Girls played a role in doo-wop sounds and R & B evolving into what is now considered Northern Soul.****

Balk went on to establish the Inferno Records in 1967 with John Rhys and Barney "Duke" Browner. The label released singles by the Volumes, Dena Barnes, and the Detroit Wheels before it was bought by Berry Gordy in 1968. Balk then joined Motown as head of A&R, and was given responsibility for setting up a new subsidiary label which would bring rock music acts to the Motown roster. He found a Detroit band called the Sunliners, renamed them Rare Earth, and helped Barney Ales establish the Rare Earth label as a Motown subsidiary.

The band Rare Earth became Motown's most important white act, charting Top 20 singles with "Get Ready", "(I Know) I'm Losing You", "Born To Wander", "I Just Want To Celebrate", and "Hey Big Brother" in 1970 and 1971. The Rare Earth label also recorded the Pretty Things, SRC, Meat Loaf, R. Dean Taylor, and Kiki Dee.

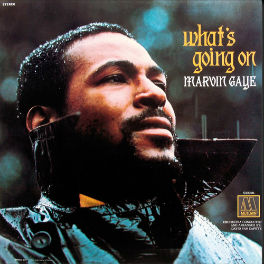

In 1971, Harry was given a stack of acetate records to listen to, and among them was the demo for "What's Going On". Berry Gordy had been asking for a record from Marvin Gaye but he hated the track and wouldn't let it be released.*

At first glance, Harry Balk would seem an unlikely champion for such a progressive record. He was an industry veteran who had guided the careers of such Michigan rock stalwarts as Little Willie John, Del Shannon, and Johnny and the Hurricanes, but he was also overseeing much of Motown's creative department while Berry Gordy spent most of his time in California.*

"One day this Marvin Gaye acetate was sent to me by mistake, mixed in with some white product," Balk explained. "I just fell on the floor when I heard it. I loved it, and made a tape of it before sending the acetate on. I listened to it over and over, and fell more in love with it. I started playing it for people who came into my office. Of course, now everybody will tell you how wonderful they thought "What's Going On" was, but I played it for the hot producers and got nothing but negative opinions. The only one that was really knocked out with it – the only one – was Stevie Wonder," Balk recalled.*

Balk's pitch to Berry Gordy was no more successful. "Berry called me and said we have to get some Marvin Gaye product out", Balk remembered. "I told him I couldn't get Marvin in the studio. He wanted to be football player, a boxer, a lumberjack – anything but a singer. When I brought up "What's Going On" he didn't want to know. 'Ah, that Dizzy Gillespie stuff in the middle, that scatting, it's old', Gordy said. "I told him it wasn't old, that the way Marvin had put it together was new. Nobody wanted to know."*

In the end, it was Marvin's stubbornness that carried the day. "We needed a Marvin Gaye record desperately," admitted executive vice-president Barney Ales. "He made sure that's the one that was released, because it was the only one we had." Harry and Barney Ales released the record behind Berry Gordy's back. Within a month "What's Going On" had gone to the top of the Billboard R&B singles chart and the album of the same name became Motown's greatest selling album of all time.*

The corporate world was hard for Harry, however. Just as he wasn't concerned about going

against Berry Gordy and releasing "What's Going On", Harry often argued with other executives and eventually left Motown in 1977. In one memorable incident, he confronted an IRS agent who came to audit him at the Motown offices, and Harry thought it was appropriate to throw him down a flight of stairs.*  Harry Balk

Harry Balk

After Motown, Harry Balk had a hard time, and the IRS took whatever money he had. In 1978, Harry suffered health problems and was living in a one-bedroom apartment. He sold most of the rights to his hit songs to pay for his doctor bills. Balk was sure his music career was over, but he again made history as the creative consultant to producer Michael Robert Phillips during the recording of the album, "A Tribute To Ethel Waters". The record featured Diahann Carroll with the Duke Ellington Orchestra under the direction of Mercer Ellington, and it was the first commercial digital recording released in the United States.*

Balk lived for a number of years in California, where he set up another record label, Avatar, before returning to Detroit in later life. He died in 2016, at the age of 91, in Oak Park, Michigan.

Because of his many contributions to the legacy of Michigan rock and roll, Harry Balk was inducted into the Michigan Rock and Roll Legends Hall of Fame in 2019 as an Honorary Inductee.

Sources:

*Harry Balk's Biography by Laura McCallister 2019

**Grit, Noise, And Revolution by David A. Carson 2005 University of Michigan Press

***John Rhys Interview www.bluepower.com 1999.

****Twirl Records by Brian C. Young 2009.