Although his career was unexpectedly derailed by a violent act and his death remains shrouded in mystery, Little Willie John is fondly remembered as Detroit’s first solo R&B star. Billed as "the prince of the blues", he was also one of the artists who helped usher in the Rock and Roll movement in American music. While still a teenager, Willie charted 5 songs on Billboard’s R&B chart including the # 1 hit “Fever”. His signature tune also crossed over to Billboard’s Hot 100, the first of 14 recordings that he would place on the chart from 1956 to 1961.

Willie was born in Cullendale, Arkansas, on November 15, 1937, the fifth child born to Lillie and Mertis John. The John family moved to Detroit in 1941, part of the large migration from the South that drew blacks and Appalachian whites to the factories that became the “arsenal of democracy”. When America entered the Second World War, the Motor City needed workers to keep production going twenty-four hours a day, and the opportunity for good paying jobs in Detroit helped increase the city’s black population from 149,119 in 1940 to 300,500 by 1950.  Willie with his parents Lillie and Mertis John

Willie with his parents Lillie and Mertis John

Unfortunately, Detroit was still a segregated city in the 1940s and blacks were relegated to the Black Bottom area located on the near east side of the city. In the overcrowded conditions of that time, the John family was fortunate to have a place of their own. Their project house on Dequindre, which located just south of Six Mile Road, was originally built as temporary housing for wartime workers, but by the mid-1940s, the area had been set aside for Detroit’s black population.

Because the project houses were basically drywall slapped up into square boxes, the area became known as ‘Cardboard Valley’. The neighborhood was safe enough, however, for residents to leave their doors unlocked, allow their children to play in the streets, and spread blankets on the grass in the summer heat to sleep under the stars.

Their house was located across the street from the Stubbs’ family home. Levi Stubbs, later of The Four Tops, was a boyhood friend of Willie John. They both loved to sing, and Levi was no doubt attracted to Willie’s lively personality and penchant for mischief and money-making schemes; but he also experienced some of his friend’s occasional epileptic seizures that could be brought on by fatigue or stress. Despite the shame that was associated with epileptic seizures in the 1940s and 1950s, the disorder did not seem to be a major problem during Willie’s childhood. It was only in his later years, when he was a touring musician, that the seizures would cause difficulties, especially if he wasn’t eating well or if he was drinking too much or taking too many drugs.

Detroit’s exploding black population caused a sharp growth in the number of black churches. The city became a major stop on the gospel circuit, and ministers like the Reverend C.L. Frankiln, Aretha’s father, would host visiting gospel stars such as the Dixie Hummingbirds, the Mighty Clouds of Joy, and the Soul Stirrers featuring Sam Cooke. These black Detroit churches would become proving grounds for a host of local singers, gospel quartets, and choirs.  Willie in the United Five

Willie in the United Five

Willie discovered the power in his voice as a six year-old member of the United Five, a gospel group that included his four older siblings. Willie’s powerful young voice elicited fervent responses among church ladies and resulted in the group being added to gospel programs in Detroit that often featured some of the touring stars of the genre.

Although gospel would always be a part of Willie’s vocal approach, he was also heavily influenced by the jazz and blues he heard on the radio as well as at Joe’s Record Shop, located at 3530 Hastings Street, not far from Willie’s home. Hastings Street was Detroit’s black entertainment center; and from the age of 12 onward, Willie would slip out of his bedroom window at night and make his way to the bright lights of the theaters and clubs that featured Detroit’s hottest music.

Amateur talent shows were very popular in Detroit during the 1940s and 1950s. Willie was an active participant along with future Michigan legends Jackie Wilson and Smokey Robinson. In 1952, Willie was discovered by bandleader and King Records’ talent scout Johnny Otis at the Paradise Theater on Woodward Avenue. Hank Ballard and Jackie Wilson also performed at the same show. Otis ended up signing Ballard to a contract with King because he thought that Willie was too young (15 years-old) to be on the label.

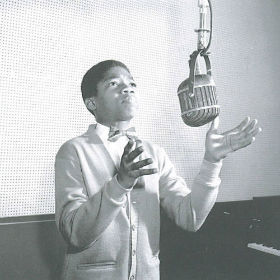

It was at another such event at the Rogers Theatre in 1953 that Willie John was first seen by his future manager Harry Balk. Although he had no prior experience, Balk recognized that Willie was a major talent and, along with his business partner Frank Glussman and record producer Dave Usher, convinced Willie’s parents to sign a managerial contract for their teenaged son.  Little Willie John

Little Willie John

Willie’s first recording was a hokey holiday song called “Mommy, What Happened to Our Christmas Tree?”. He was only 15 years-old and a student at Detroit’s Pershing High School. The song was recorded in November of 1953 at the United Sound studio on Second Avenue in Detroit with a studio band and a group of professional background singers. The record was pressed into hard shellac 78s at the American Record Pressing Plant located on M-21 in Owosso, Michigan, and issued on the Prize label as by ‘Willie John and the Three Lads and a Lass’.

The novelty song was a big hit on Detroit radio and Willie was interviewed by both the Detroit Times and the Detroit News. His managers achieved an even bigger coup in early December when Willie was mentioned in Dorothy Kilgallen’s powerful, nationally syndicated show business column. Flushed with success, Balk and Usher took Willie to New York where he appeared on television and made an impression at a benefit at the famed Apollo Theater in a line-up that included Duke Ellington, Ruth Brown, Nat “King” Cole, and the Drifters. After returning to Detroit, his managers started billing him as 'Little Willie John'. He was then booked on a brief tour in cities where his record was selling and at a big variety show at the Michigan State Fairgrounds.

Willie left Pershing High in early 1954 to go on the road with bandleader Paul Williams. Williams, who had spent his childhood in Kentucky, moved with his family to Detroit at the age of 13. He started his recording career in 1947, and in 1949 had a gigantic hit with his sax-driven instrumental, “The Hucklebuck”, which spent 14 weeks at # 1 on Billboard’s R&B chart. Willie recorded his second single, “Ring a Ling”, with Williams in New York. It was released on George Goldner’s Rama label in early 1955 but did not chart.  Willie with Detroit Pershing High cheerleaders

Willie with Detroit Pershing High cheerleaders

Williams dropped Willie from the orchestra several months later after he began acting up, hanging with a rough element, and getting involved in gambling parties. Willie landed on his feet, however. Besides lining up an audition with King Records, Willie struck up a friend ship with Detroit-born boxing legend Sugar Ray Robinson and his wife Edna and stayed in their home in New York for a time.

Willie was signed to King Records by Henry Glover, the label’s most important producer and A&R man. Just hours after he had been signed, Willie was in the Beltone studio in New York to record his first King single, the bluesy “All Around The World”, with a top-notch group of session players that included Mickey “Guitar” Baker, Willis “Gatortail” Jackson on tenor sax, and “Champion” Jack Dupree on piano. In the song, Willie lists all the things that couldn’t be true if he didn’t really love his baby (If I don’t love you, grits ain’t groceries, eggs ain’t poultry and Mona Lisa is a man). "All Around The World" quickly became a major hit, soaring up to # 5 on the R&B chart. In 1969, Little Milton would cover the song under the title “Grits Ain’t Groceries (All Around the World)” for a # 13 R&B hit.

The success of “All Around The World” put Willie at the top of the bill for a week in September at the Apollo Theater before embarking on the Lucky Seven rhythm and blues bus tour of theaters on the East Coast that comprised part of the chitlin circuit for black artists. The grueling run of one-nighters, which included Michigan stops in Detroit and Saginaw on the Midwestern leg of the tour, also played in a host of cities in the South before moving on to more dates on the West Coast.

His second single, “Need Your Love So Bad”, was recorded in New York shortly before Willie went out on the Lucky Seven tour. Much of the song had been written by Willie’s older brother, Mertis Jr, while he had been stationed in Korea. Willie finished the song his brother brought to him and recorded the definitive version of "Need Your Love So Bad" in September of 1955. It was released two months later in the midst of the tour and peaked at # 5 on the Billboard R&B chart early in 1956.

Despite his hits, Willie wasn’t making much money from his record sales. He soon discovered that Syd Nathan of King Records would buy him a new Cadillac in lieu of cash payment, and Willie quickly obtained the first of many new Cadillac vehicles. Touring was where the real money was for black artists in the 1950s, and Willie performed at the Second Annual Rock ‘n’ Roll Jamboree in Los Angles on a bill with B.B. King, Smiley Lewis, and Otis Williams and the Charms. The following month he joined the Rhythm & Blues Review with The ‘5’ Royales, Roy Brown, Joe Tex, and Percy Mayfield.

There is some dispute as to whether Willie’s biggest R&B hit, “Fever” was recorded in New York or Cincinnati, but there is no doubt that it was his signature song. There is also some controversy as to who wrote the song. Most agree that Otis Blackwell wrote at least part of “Fever” using the pseudonym of John Davenport because he was under contract to another company. Blackwell has stated that his friend Eddie Cooley brought him a rough version of the song and that he finished it; but Blackwell has also stated on another occasion that he wrote “Fever” with Little Willie John.

“Fever” was released in April, 1956, and was an immediate hit. It topped Billboard’s R&B chart for five weeks and became Willie’s first crossover hit when it went to # 24 on the Billboard Hot 100, eventually selling over one million copies. Willie also charted with “Fever’s” b-side, “Letter From My Darling”, which was a # 10 R&B hit. There one other statistic that is even more telling of “Fever’s” immense popularity. The song was the # 6 most played jukebox song of 1956, according to Billboard. What makes “Fever’s” showing even more impressive is the fact that 1956 was Elvis Presley’s breakout year in which he completely dominated the music business. Elvis charted an amazing 17 songs on the Hot 100 including 5 # 1 singles, as well as 6 Top Ten hits on the R&B chart.

The song has had an interesting history well beyond Little Willie John’s classic recording. Two years later in 1958, Peggy Lee recorded a version of the song with altered lyrics and a different musical arrangement. Lee’s “Fever” was a bigger pop hit than Willie’s, reaching # 8 on the Hot 100. It was also nominated for Record of the Year and Song of the Year at the 1st Grammy Awards in 1959 and is widely regarded as Lee’s signature song.

In addition, Elvis Presley recorded a version of “Fever” for his “Elvis Is Back!” album in 1960. Five years later, The McCoys had a # 7 hit with “Fever” as their follow-up single to “Hang On Sloopy”. Rita Coolidge also charted with the song in 1973, peaking at # 76 on the Hot 100. In 1992, Madonna recorded a version of “Fever” for her “Erotica” album and it became# 1 hit on the Hot Dance Club chart as well as a popular video. “Fever” has also been recorded by both Bette Midler and Beyonce; and it was one of the featured numbers in the hit Broadway musical Million Dollar Quartet which opened in New York in 2010.

Unfortunately, neither Willie nor King could come up with a follow-up hit to match the success of “Fever” for almost two years. “Do Something For Me” was released as a single in November of 1956 but it was only a # 15 R&B hit. For the next year and a half, however, Willie experienced a dry spell in which all seven of his singles failed to chart.

Despite this fallow period, Willie, who was now billed as “the prince of the blues”, continued to be the consummate live performer who appeared on bills in venues all across the country. Whenever possible, Willie tried to avoid performing in the segregated South. During the summer months some of his favorite bookings were in the clubs at Idlewild, Michigan. The lake town was located south of Ludington and near the Lake Michigan shore. Its hotels, motels, nightclubs and stores were largely owned by black people and attracted a high caliber of black entertainment including Willie’s boyhood friend Levi Stubbs and the Four Aims.

In 1957, Willie met dancer Darlynn Bonner at the Apollo Theater. The pair fell in love and married that summer in Detroit. The couple had their first son, Kevin, the following year.

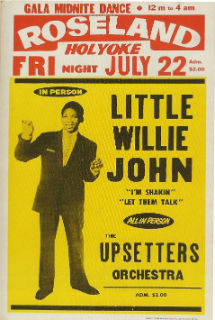

After Little Richard abruptly quit rock and roll and enrolled in a seminary, Willie hired his fabulous band, the Upsetters, to back him on the road, thereby making his live act even more dynamic.

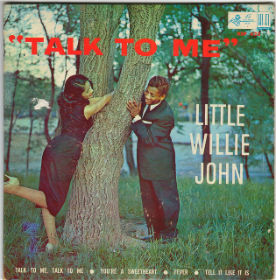

Willie finally returned to the charts in the spring of 1958 with his classic ballad, “Talk To Me”. On May 6th, he made his debut on American Bandstand lip syncing his new hit as well as “Fever”. “Talk To Me” became his biggest hit in two years, reaching # 5 R&B and crossing over to # 20 on the Hot 100.

Little Willie John’s next two singles in 1958, the ballad “You’re A Sweetheart” and the bluesy “Tell It Like It Is”, were R&B hits but did not cross over to the Pop charts. During this time, Willie’s older sister, Mabel John, had begun working with songwriter Berry Gordy Jr. Gordy reportedly offered Willie some of his songs, but Willie turned them down. Jackie Wilson, on the other hand, took Gordy’s songs and the Detroit native had four consecutive Top Ten singles on the Billboard R&B chart, including the # 1 hit “Lonely Teardrops”. After Berry Gordy formed Motown, Mabel John became the first female solo artist to be signed by the company.

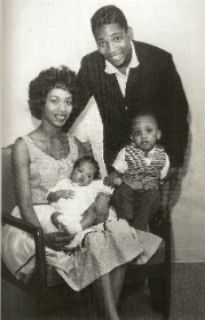

The rocking “Leave My Kitten Alone” was Willie’s first hit of 1959, peaking at # 13 R&B and crossing over to # 60 on the Hot 100. It’s easily one of Willie’s best recordings with the “meows” of the female backing vocals surrounding Willie’s dire warnings to a romantic rival of what would happen to him if he didn’t leave his girl alone. “Leave My Kitten Alone” was a big favorite of John Lennon and the Beatles, who often performed it live in 1961 and 1962 and recorded a cover version in 1964.  Willie and family (L to R) Darlynn, Keith, Kevin

Willie and family (L to R) Darlynn, Keith, Kevin

1960 was a good year for Little Willie John. His second son, Keith, was born in late January. The next month, his ballad “Let Them Talk” reached # 11 on Billboard’s R&B chart and managed to reach # 100 on the Hot 100.

Willie’s next single, “Cottage For Sale” did not make the R&B chart but hit a respectable # 63 on the Hot 100 in the spring. It’s hard to believe that the record’s tremendous b-side, “I’m Shakin’”, wasn’t a hit. One of Willie’s best rockers, it is usually missing in action on most of the anthologies of the singer. Many music fans heard the song for the first time on the four-CD Rhino Records box, “Loud, Fast & Out of Control: The Wild Sounds of 50’s Rock”. In 2012, Detroit-born rocker Jack White also brought attention to one of Willie's underappreciated tracks when he recorded a great cover of “I’m Shakin’” on his hit album “Blunderbuss”.

In June of 1960, Willie recorded the sizzling “Heartbreak (It’s Hurtin’ Me)”. With its piercing, soulful wail, a trio of funky saxophones chugging behind him and a wild organ that seemed to be torn between the church and the saloon, the song became Willie’s first Top 40 single since “Talk To Me". “Heartbreak (It’s Hurtin’ Me)” rose to # 11 on the R&B chart that summer and quickly became a show-stopping number on stage for Willie and The Upsetters.

Willie wanted to use the Cincinnati Symphony for his recording of “Sleep”, an old song that had been a # 1 hit for Fred Waring’s Pennsylvanians in 1924. When Willie found out he would have to pay for the symphony, he settled for a string quartet that was overdubbed three times on the final recording. Somehow it all worked out, and “Sleep” became his biggest hit on the Hot 100 in the fall of 1960 when it reached # 13. The song also earned the # 10 spot on the R&B chart; the seventh time Willie had placed a single in the Top Ten.

Strings were also prominent on “Walk Slow”, Willie’s follow-up to “Sleep”, released late in 1960. The pleasing ballad didn’t chart as high as its predecessor, however, peaking at # 21 R&B and # 48 on the Hot 100.

After Johnny Preston issued a cover of “Leave My Kitten Alone” on the Mercury label in January of 1961, King Records re-issued Willie’s original version of the song. Preston’s version peaked at # 73 on the Hot 100 while Willie’s re-issue hit # 60, the exact same chart position that the original release of “Leave My Kitten Alone” had achieved back in 1959.

“The Very Thought Of You” followed the same pattern as “Sleep” in that it was a decades old song that had originally been a hit for Ray Noble back in 1934. Willie’s update of the song reached # 61 on the Hot 100 but the tastes of the record buying public were starting to change and some of King’s biggest stars, including Hank Ballard and the Midnighters and Little Willie John, were selling fewer records.

Willie tried to update his sound when released the spritely single “(I’ve Got) Spring Fever” in the spring of 1961. It fit right in with other current teen-oriented releases, but it only reached # 25 on the R&B chart and # 71 on the Hot 100. The single’s b-side, “Flamingo” used the same basic formula as “Sleep”, and the string-drenched recording actually did better than the a-side on the R&B chart, peaking at # 17.

Little Willie John’s last successful record was “Take My Love (I Want To Give It To You)” backed with “Now You Know”. The rocking “Take My Love” was a big R&B hit for Willie, spending 11 weeks on the chart and peaking at # 5. Both sides charted on the Hot 100 with Take My Love reaching # 87 and “Now You Know” # 93.

Nothing that Willie released in 1962 clicked with record buyers. “Mr. Glenn”, which was about astronaut hero John Glenn, the country tune “She Thinks I Still Care”, and covers of previous R&B hits, including “The Masquerade Is Over” and “Every Beat Of My Heart”, were all sales flops. He also tried re-releasing two of his old hits; “Fever” and “Need Your Love So Bad”, but nothing was selling. The charts were now dominated by a bevy of young Motown artists, Phil Spector’s 'Wall of Sound' recordings, solo artists including James Brown, Dion, and Gene Pitney, and new vocal groups like the 4 Seasons and the Beach Boys.

Little Willie John had always been a party animal on the road, but the years of heavy drinking and drugging seemed to be taking their toll. Willie’s first big scrape with the law came when he was taken to court for racking up almost a thousand dollars in long distance charges on a phony credit card.

Like many other entertainers during the 50s and 60s, Willie carried a gun for protection and sometimes to deal with dishonest promoters. But there were also troubling incidents in which Willie was very careless in the way that he brandished the firearm, especially if he had been drinking.

Five more singles were released in 1963. The catchy “My Baby’s In Love With Another Guy” had solid hit potential, but by this time Willie had completely fallen out of favor with the teen audience. As his record sales dwindled, he was no longer getting the best gigs. Worse, he was missing more and more scheduled appearances. Because Willie’s schedule was becoming more and more erratic, the Upsetters began backing up Sam Cooke, Chuck Jackson, and the ‘5’ Royales between 1963 and 1964.

Willie’s downward spiral seemed to intensify after he split with his dynamite backing group, the Upsetters. They were a well-known show band, and without them, Willie’s gigs were smaller and the pay less. The beginning of the end came after a weekend booking in October of 1964 at a dumpy club called the Magic Inn in Seattle. After the last show, Willie was partying with a couple of women and ended up at an illegal drinking establishment. An argument ensued; and an ex-con punched Willie who apparently retaliated by stabbing the man in the chest with a steak knife, resulting in his death.

Willie was booked on suspicion of murder. He pleaded not guilty and posted a $10,000 bond. Willie continued to perform while out on bail and awaiting his trial. By all accounts the eventual trial was something of a fiasco. Multiple witnesses changed their stories and Willie’s defense attorney did not pursue a self-defense verdict in a situation where the victim was almost twice the size of Willie. In addition, there were no witnesses to the actual stabbing. Instead, his primary defense was that Willie suffered an epileptic seizure and couldn't remember the events of the fateful evening.

His defense attorney also did not seem to adequately prepare Willie for the witness stand where he came off as arrogant and boastful to the middle class, all-white jury. Although he had been charged with second-degree murder, Willie was convicted on the lesser charge of manslaughter.

Pending sentencing, Willie posted a $20,000 bond and left the state to fulfill some tour dates and generate some much-needed cash before he was due back in court. His attorney filed for a new trial, but that was denied. He then filed an appeal, but claimed he couldn’t find Willie to get the $1,500 deposit. Willie was returned to Seattle by federal marshals in May and shortly thereafter dismissed his defense attorney. The appeal was dismissed on May 6th for lack of action.

While he was awaiting sentencing, Willie signed a recording contract with Capitol Records. He had not recorded for King in 1965 and thought that his contract with his old company was over. Capitol was Frank Sinatra’s former label, and Sinatra had long been one of Willie’s idols, both for his recordings and for his style of dress.

Willie recorded 11 tracks for an album with David Axelrod and HB Barnum; but before he had a chance to overdub his vocals, King Records threatened to sue Capitol claiming that Willie was still under contract. As a result, Capitol put Willie’s recordings on the shelf in their vault where they would remain for over 40 years. In 2008, Ace/Kent Records in Britain licensed the songs from Capitol and released the CD “Nineteen Sixty-Six – The David Axelrod and HB Barnum Sessions”. It was only available in America as an import.

Willie was sentenced to eight to twenty years at the Washington State Penitentiary. The sentence seemed extremely harsh in light of the lack of evidence. A letter writing campaign asking for his parole was undertaken, but Willie died unexpectedly in the prison hospital on May 26, 1968. The cause of death listed in the prison medical examiner’s report and on his death certificate was “massive acute myocardial infarction” or heart attack.

Just four months earlier, Willie had written his wife saying that he was in good health. Since he had no apparent history of heart disease, it seemed unusual and suspicious that a man of 30 years would so suddenly succumb to a heart attack. Although the death certificate stated that an autopsy was performed to determine the cause of death, there is no copy of any such autopsy report. There were rumors of murder and conspiracies but the mystery surrounding his death will most likely never be solved.

By 1995, Little Willie John had been nominated seven times for induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame without being voted in, but his eighth nomination proved to be the charm. The Hall of Fame’s Class of 1996 included Willie along with Pink Floyd, David Bowie, the Velvet Underground, Gladys Knight and the Pips, and the Shirelles. Stevie Wonder gave Willie's induction speech and shared that, as a little boy, he grew up listening to the music of Little Willie John on the radio. Stevie also spoke of the joy he felt being the one to induct a great talent, someone who inspired him to be an artist, into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

In 2016, Little Willie John was selected as a Historical Inductee to the Michigan Rock and Roll Legends online Hall of Fame.

SOURCE: Most of the above information was taken from the excellent biography Fever: Little Willie John – A Fast Life, Mysterious Death and the Birth of Soul by Susan Whitall with Kevin John. 2011. Titan Books.