In a perfect world a Detroit native who recorded the first Tamla single and whose hits helped establish the Motown Record Corporation would not be left out of the label’s illustrious history. Al Abrams, Motown’s former director of advertising and public relations, states it best; “The main thing to me is that Marv Johnson is an unsung hero of Motown. It’s criminal that he’s not mentioned or acknowledged in Berry’s play (Motown The Musical). There’s no mention of Marv, of “Come To Me”, or United Artists. Come on, there wouldn’t have been a Motown without Marv Johnson!”

The man that Motown has forgotten was born Marvin Earl Johnson on October 15, 1938 in Detroit, Michigan to Elizabeth and Johnny B. Johnson. Marv showed an aptitude and love for music at an early age after he was exposed to gospel music in Baptist churches and R&B from the recordings of Louis Jordan that he heard on the radio.

For a short time during his early years, Marv was sent to live with an uncle in Crenshaw, Mississippi. There he was exposed to rural music and developed a fondness for the blues of Sonny Boy Williamson. Returning to Detroit while still in elementary school, Marv would be further influenced by the sounds of early rhythm and blues recordings by Ruth Brown, The Clovers, and The Drifters.

By the time Marv graduated from a study program of auto-aero mechanics at Cass Technical High School, he had acquired rudimentary skills as a pianist and had joined a singing group composed of boys from his neighborhood called The Junior Serenaders.

Homer Jones, a local band manager who had at one time handled both Jackie Wilson and Little Willie John, took a liking to the young group and got them booked as a midway attraction at the Michigan State Fair in Detroit. From there, The Junior Serenaders followed the black tent show circuit and played many small towns in the Midwest and South. After several original members wearied of the grind and dropped out, Marv soldiered on as a solo act. He wanted to stick with music and was paying his dues on the road when he was involved in a terrible automobile accident that took the lives of several of his traveling companions.

According to biographer Joseph F. Laredo, Marv returned to Detroit in 1958 and took a job at the Prince Adams Record Mart on 12th Street and Hazelwood, an area that later figured prominently in the riots of 1967. There he met Sonny Woods, a local producer who had performed with Hank Ballard & The Midnighters. Woods was working with a group called The Downbeats and invited Marv to a rehearsal at Specialty Studio. Marv performed some original material and was invited to join the group. At this time, his main stylistic influences were Jackie Wilson, Clyde McPhatter, and Sam Cooke.

It’s not certain where Berry Gordy first saw Marv Johnson sing, but many Motown experts believe that Gordy’s Rayber Voices (Raynoma Liles, Brian Holland, Robert Bateman and Sonny Sanders) did the backing vocals on Marv’s first single. “My Baby-O” was a Sonny Woods’ composition that was issued on Robert West’s Kudo label in 1958. Marv’s debut was recorded at United Sound in Detroit and backed by the band of Harold “Beans” Bowles. “My Baby-O” would represent both Johnson’s and Gordy’s initial step towards what would eventually become the first Tamla 45.

Robert West was one of the most prolific producers/label owners in Detroit at that time and an early inspiration for Berry Gordy. West issued some seminal R&B recordings on a variety of labels including Flick, Lu Pine, and Kudo. His greatest achievement was his discovery and recordings of The Falcons, which launched the singing careers of four legendary soul singers; Eddie Floyd, Joe Stubbs, Sir Mack Rice, and Wilson Pickett. In addition, West recorded the first singles by later Motown stalwarts Brian Holland and The Primettes (later renamed The Supremes).  Early publicity photo

Early publicity photo

Berry Gordy had formed the Rayber Music Writing Company with his soon-to-be-second wife Raynoma Liles in 1958, but quickly determined that label ownership and control of record distribution was where the real money could be made. After learning that Marv had composed some original songs, Berry and Raynoma visited him at the record store where he worked, and he played them his composition of “Come To Me” on a piano in the back of the store.

Berry and Raynoma were knocked out by the song’s potential, and it was decided that Marv Johnson was the right artist and “Come To Me” was the right song to launch their new Tamla record label. After Gordy made a few changes to the song, “Come To Me” was recorded at United Sound along with another Johnson original called “Whisper” as its flipside. Supporting Marv on both tunes were the Rayber Voices.

Issued as Tamla 101 in January of 1959, “Come To Me” generated a lot of excitement in Detroit. Sensing a hit, Gordy traveled to New York and secured a national distribution release for the record through Art Talmadge at United Artists, but retained the distribution rights for Tamla in Michigan. “Come to Me”, released on United Artists label in February, was a big success, rising to # 6 on the Billboard R&B chart and to # 30 on the Hot 100. It would the first of many hits for Berry Gordy’s young company.

Talmadge was impressed with Marv Johnson and signed him to their artist roster with Berry Gordy acting as his manager. Although it seemed that the combination of a high-powered national label and the support of Detroit’s creative talents gave him the best of both worlds, the partnership would unravel in a few short years and Marv Johnson would find himself adrift by the mid 1960s.

But in 1959, everything was coming up roses for Marv Johnson. He began appearing at prestigious venues like the Apollo Theater in New York and the Howard Theater in Washington D.C. He also appeared on some of the early rock and roll shows promoted by Alan Freed.

Marv’s less successful follow-up was released in May of 1959. “I’m Coming Home” was written by Berry Gordy and was reminiscent of some of the songs he penned for Jackie Wilson. The single peaked at # 23 on the R&B chart but only reached # 82 on the Hot 100.

Al Abrams joined Tamla in May of 1959. Marv was one of the first people he met at the label, which at that time was located in Berry and Raynoma’s apartment at 1719 Gladstone St. in Detroit. Abrams was Jewish; and when they were introduced, Johnson completely surprised Abrams by greeting him in Yiddish. Marv later revealed to Abrams that he picked up some Yiddish from the Jewish people who lived in his apartment building. The two hit it off pretty quickly. Abrams wrote Marv’s first biography for United Artists, and he drove him to record hops and TV shows when he wasn’t traveling around the country visiting DJs and promoting Johnson’s latest records.

In a recent interview, Abrams said that Marv Johnson always struck him as being a solid professional. He recalled that Marv was the headliner on the prototypes of the celebrated Motown revues which included the label’s other early artists: The Miracles, Eddie Holland, Barrett Strong, Mabel John, and The Satintones. These shows were performed in front of predominantly black audiences and were presented at both the Flint IMA and the Saginaw Auditorium, as well as venues in other Michigan cities with large African American populations.

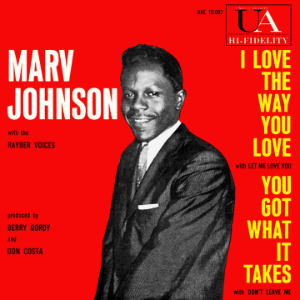

Up until 1961, Johnson was the only Motown-related artist who had recorded a Top Ten hit single. The first of these was the infectious “You Got What it Takes”, released in August of 1959. “You Got What It Takes” was credited to Berry Gordy, Billy Davis, and Gwen Gordy. The single reached # 2 on the R&B chart, and it was a massive hit on the Hot 100, peaking at # 10 and staying on the chart for an incredible 22 weeks. On October 26, Marv Johnson made his national television debut perfforming his big hit on Dick Clark's American Bandstand.

Johnson's importance to what would soon become the Motown Record Corporation was clearly illustrated in Jerry Kabel's Detroit Times column on Thursday, February 25, 1960. It was the first mainstream newspaper article about the young company. Al Abrams was quoted as saying, "The best thing we've got going right now is 'You Got What It Takes' by Marv Johnson." Berry Gordy also commented on the hit in the article; "You can hear how the song tells a complete story," said Gordy. "It's the story of a man who loves a girl even though she's unattractive in some ways." Smokey Robinson was the only other Motown artist mentioned in the story, but his first big hit with The Miracles ("Shop Around") was still nearly a year in the future.

Although "You Got What It Takes" made Marv Johnson a star, blues guitarist Bobby Parker had cut a virtually identical song by the same title back in 1957 for Chicago’s Vee-Jay Records and Parker was credited as the sole composer. Apparently a deal was made to cover Parker’s song, but no one seems to be willing or able to explain the subsequent change in writer’s credit.

There was no controversy surrounding Marv’s fourth consecutive charting single, “I Love The Way You Love”. Featuring Benny Benjamin’s driving drumbeat, Beans Bowles' airy flute, and the enticing backing vocals of the Rayber Voices, it became Marv’s biggest hit, peaking at # 9 on the Hot 100 and # 2 R&B in early 1960.

Al Abrams was one of the co-writers of the song and has clear memories of how it was composed. Abrams recalled that in the early days, Berry Gordy would throw out a line if he had an idea for a song to see if anyone could come up with a follow-up line to rhyme with it. If someone came up with something he liked, he would then go on to the next line.

Abrams remembered that he, Gordy, Berry’s driver John O’Den, and Raynoma’s brother Mike Ossman were in a car driving back from a show in Cleveland that starred Little Willie John and Jackie Wilson. They threw lines back and forth to a new Gordy song idea all the way back to Detroit. By the time they arrived, the four of them had completed the lyrics to what would become Marv’s 2nd Top Ten hit. Although Abrams is justifiably proud of his contribution to “I Love The Way You Love”, he disclosed that it took 47 years before he saw a royalty check.

March of 1960 saw the release of Marv’s first United Artist album, “Marvelous Marv Johnson”. Typical of albums of the time, it surrounded some of the singer’s hits with seven Tin Pan Alley standards that had limited appeal for Marv’s young fans. On the other hand, the “More Marv Johnson” album, issued just three months later, was right in his wheelhouse. It was produced by Berry Gordy and consisted entirely of early Motor City soul. Besides some of his hit singles, the album included Marv’s composition, “This Heart Of Mine”, the Johnson/Gordy/ Smokey Robinson collaboration “Clap Your Hands”, and Gordy and Bradford’s “When You’ve Lost Your Love”.

Both sides of Marv Johnson’s next single charted in the Hot 100 in the summer of 1960. The a-side, “All The Love I Got”, was penned by Gordy, Holland, and Bradford. The up-tempo cut prominently featured “Beans” Bowles’ flute and was the bigger hit, although at a somewhat disappointing # 63. Its chart position may have been hurt by the Gordy/Johnson b-side, “Ain’t Gonna Be That Way”, which battled for airplay and reached a respectable # 74.

Marv’s last Top 40 hit, “(You’ve Got To) Move Two Mountains”, peaked at # 20 on the Hot 100 and # 12 R&B in the fall of 1960. Written by Berry Gordy, the gently recriminating number included a sax solo, a new touch on a Marv Johnson single.

Unfortunately, the catchy “Happy Days” didn’t do as well in early 1961, failing to make the Top 40 and peaking at # 58. The flipside, Johnson’s composition of “Baby, Baby” was the polar opposite of the Detroit sound with its lush orchestration and production.

It was during this time that Marv and 19-year-old Aretha Franklin became an item. In May of 1961, Jet magazine reported in its New York Beat column that "Marv Johnson and Aretha Franklin, the Detroit preacher's daughter, are not telling friends of their hot romance, which could lead to the altar." Their affair was short-lived, however, as Johnson was pursuing his own career and couldn't give Franklin all the attention she required as she was beginning her secular recording career at Columbia Records in New York City. Aretha married Detroit music hustler/manager Ted White later in 1961, despite the objections of her father Reverend C. L. Franklin. Their tempestuous marriage, which involved alcohol abuse and domestic violence, ended in divorce in 1969.

Marv Johnson’s next single, the Gordy-penned “Merry-Go-Round”, also used the heavily orchestrated production of United Artists’ New York studio. Berry Gordy’s concentration was increasingly focused on his fledgling Hitsville operation in Detroit. It would be Marv Johnson’s last hit for United Artists on both the Hot 100 (# 61) and the Billboard R&B chart (# 26).

To increase Marv’s mainstream appeal, he was signed to appear in a dreadful, low budget rock and roll movie called Teenage Millionaire in 1961. The basic film was shot in black and white but the music acts, which also included Dion, Chubby Checker, Jackie Wilson, and Bill Black’s Combo, were shown in a chintzy coloring process called Musicolor. Marv performed both sides of his new single, “Show Me” and “Oh Mary” in the film. Although the latter song was written by Berry Gordy and Mickey Stevenson, neither song broke into the Hot 100.

Marv Johnson’s cold streak continued through the end of 1961 as his next single, the Smokey Robinson composition “Easier Said Than Done”, also failed to chart.

When Marv’s initial contract with United Artists was up for renewal in 1962, Berry Gordy approached him and asked whether he wanted to stay with the label or come over to Motown. Years later, Johnson said that he was puzzled by Gordy’s question and shared his feelings with writer Joseph Laredo: “If you’re my manager, then you should help me make that decision, don’t ask me a question and then blame me for the answer.” Marv, perhaps reluctant to leave the prestigious UA label, answered that he wanted to leave things as they were.

Although Marv started the year with the Gordy composition “Magic Mirror”, the single failed to chart and, in hindsight, it seems that his decision to stay with United Artists affected his relationship with Berry Gordy. As Gordy concentrated more and more on his company in Detroit, Marv was no longer being produced or written for by the talents at Motown. Instead, he was being recorded and handed big, new orchestrations in New York. Although he was often given material written by some of the top people in the field – Ellie Greenwich, Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, Bert Berns, and Burt Bacharach and Hal David – the heavily orchestrated records he was now making were a far cry from his Motown-flavored hits of 1959 and 1960, and nothing he released was charting.

Marv Johnson’s contract with United Artists expired in the midst of the British Invasion in 1965 and was not renewed. He returned to Detroit and signed with Motown, but it was too late. Marv recorded three singles for the Gordy label, but only 1966’s “I Miss You Baby (How I Miss You)” managed to see any chart action, reaching # 39 on the Billboard R&B chart. Marv got more recognition from the Dave Clark Five’s cover of “You Got What It Takes”, which reached # 7 in 1967, than from any of his Gordy recordings.

Despite his reversal of fortune in the United States, Marv was still very popular in England. His final Gordy single, the danceable “I’ll Pick A Rose For My Rose”, became a surprise # 10 hit in the U.K in 1969. This led to the re-release of “I Miss You Baby (How I Miss You)” in England; and it also charted, reaching # 25 that same year. The unexpected success led to a British tour and album that contained several songs unissued in the U.S.

Regardless of his triumph in England, Marv’s stock at Motown as a recording artist had dropped dramatically. He went on to work for a while in Motown’s promotional department, trading on the rapport and good will he’d built up over the years across the country, but that came to an end in the early 70’s. According to Laredo, Marv later affiliated himself with a Detroit-based company called Groovesville Productions, and used his songwriting capabilities to turn out material for soul artists such as Tyrone Davis and Johnnie Taylor.

After a prolonged layoff, Marv returned to performing in the 1980’s. He appeared mostly on “oldies” shows, often with other Motown alumni such as Mary Wells, Martha Reeves & The Vandellas, and Kim Weston. He also signed with Ian Levine’s Motorcity label and recorded one album. Sadly, Marv passed away in 1993 after suffering a stroke following a performance at a tribute concert for Bill Pinkney of The Drifters in Columbia, South Carolina. Marv Johnson’s funeral in Detroit featured songs performed by The Falcons, Kim Weston, and Pat Lewis along with spoken expressions of praise for the artist by former associates Esther Gordy Edwards and Robert Bateman.

Nineteen years after his death, Detroit musicians John and CJ Milroy discovered that the graves of both Marv Johnson and Uriel Jones of the Funk Brothers did not have headstones. The couple raised $2,300 for a proper headstone for Jones and $3,700 dollars for a memorial bench for Marv Johnson at the Woodlawn Cemetery in Detroit. John Milroy explained their motivation to WXYZ in Detroit: “It just seems like a great thing to do as a Detroiter to make sure that these musical pioneers have a memorial and a headstone and a place where people can go and visit.”

Many serious fans of Motown have been both surprised and disappointed that Marv Johnson’s contributions to the company’s success have been ignored over the years. Besides being left out of the Broadway hit Motown The Musical, he was not mentioned in Motown 25 or any of the other television productions about the label's history that have been broadcast since. In addition, “Come To Me” has been left off definitive Motown CD collections including the 4 CD “Hitsville USA: The Motown Singles Collection 1959 – 1971” and the recently released 6 CD “Motown: Big Hits & More”. The omission is both lamentable because “Come To Me” was the very first hit issued by the company, and inexplicable since Motown's Jobete Publishing has always owned the rights to the song even though it was distributed nationally by United Artists in 1959.

In recognition of Marv Johnson’s recording career and the important role that he played in the birth of Motown, MRRL selected him as the 2015 Historical Inductee to the Michigan Rock and Roll Legends Online Hall of Fame.

Important sources: Joseph Laredo's liner notes for "The Best Of Marv Johnson: You Got What It Takes" CD, Bill Dahl's book Motown: The Golden Years, and Al Abrams' book Hype & Sou! Behind the Scenes at Motown were all very helpful in the writing of Marv Johnson's biography.

Video: Watch a video of Marv Johnson's "Come To Me" by clicking here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u01a0_yDZxE

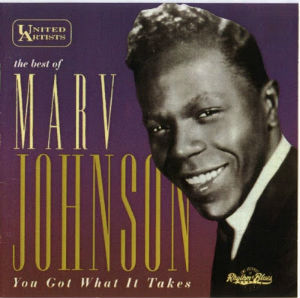

Dr. J Recommends: "The Best of Marv Johnson, You Got What It Takes" United Artists CD.

Unfortunately there are no collections that include Marv's releases on both United Artists and Gordy, but this one has all of the essential songs on the UA label. Of the album's 24 tracks, 19 deal with songs that have a definite Motown connection.

All of his Hot 100 and R&B hits from 1959 through 1961 are here along with some interesting b-sides. The last five songs are enough to show what happened to his recordings after Berry Gordy turned his attention to his stable of emerging artists at Motown in Detroit.