Motown was the dominant musical force of Detroit during the 1960’s, but by the middle of the decade there was another important musical movement that ran from the Motor City west to Grand Rapids and north through Flint to Bay City and even as far north as the Upper Peninsula. Guitar-based bands inspired by English groups like the Rolling Stones, Kinks, Beatles, and Yardbirds were recording singles on small independent Michigan labels such as A-Square, Lucky Eleven, Dicto, Hideout, and Fenton. hese Michigan rock and roll bands played a circuit of teen dance clubs including the Hideouts in both Harper Woods and in Southfield, Daniel’s Den and the Y-A Go Go in Saginaw, the Rivera Terrace and Mt. Holly in Flint, Sherwood Forest in Davison, Roll-Air and the Band Canyon in Bay City, the Fifth Dimension in Ann Arbor, and most importantly, the Grande Ballroom in Detroit.

The most notorious of all the Michigan guitar bands was the MC5. The band had its origins in Lincoln Park, a small city in Wayne County that grew as a bedroom community for the workers employed at Henry Ford’s River Rouge Plant and other mills and factories connected to the auto industry.

There, junior high school classmates Wayne Kramer and Fred Smith shared a love of Chuck Berry, and began playing guitar together after school and every day during the summer. Even though Kramer and Smith started off playing in different bands, it wasn’t long before they joined forces. After recruiting Rob Tyner as their lead vocalist along with a bassist and drummer, the group decided to call themselves the Motor City Five.

Kramer’s mother let the band rehearse and hang out at the house. She was an important factor in the band’s early development, offering an encouraging voice and even managing the band for a while as they started playing the record hop circuit at school dances and smaller teen clubs. The band’s early set list included covers of Chuck Berry, James Brown, the Rolling Stones, and Motown. Midway through 1965, Tyner convinced the rest of the band to modify their name to MC5 because it had an anonymous car factory sound that was cool, and it connected them to the teen-age car culture and drag racing world that they were interested in.

The next big step in the MC5’s development was convincing their new manager, Bruce Burnish, to take out a bank loan to finance the purchase of $3,000 Vox Super Beatle amplifiers from England. The new amps gave them the power to play at a greater volume than any other band in Detroit. At the same time, the nucleus of the MC5 realized that the way for them to be successful was not to try to sound like an average teen band trying to get a record on the charts, but to jam in a new jazz-influenced, improvisational direction. This caused members Pat Burrows and Bob Gaspar to leave the band. They were replaced by drummer Dennis Thompson and bassist Michael Davis. The classic MC5 line-up was now in place.

In 1966, the band played at a jail release party for John Sinclair, one of the founders of an artist colony and social collective called the Detroit Artists Workshop. The MC5 eventually began to use a building at the Detroit Artists Workshop as a rehearsal space and attracted the attention of jazz buff Sinclair who liked the way they played rock and roll with creativity and improvisation.

When schoolteacher, and fledgling rock impresario, Russ Gibb asked John Sinclair if he knew of a good band with an original sound to play at the new rock emporium he was opening at the Grande Ballroom in Detroit, Sinclair recommended the MC5. Gibb offered the MC5 the position of house band, although he told them he would be unable to pay them until the Grande became established. The band took the gig for both the exposure they would get and the opportunity to rehearse at the same venue where they would play.

Gibb’s plan was to develop a scene in Detroit around the Grande Ballroom that would be like the one he witnessed earlier in the year at Bill Graham’s Fillmore Auditorium in San Francisco. Opening in October, 1966, shows at the Grande were advertised on posters designed by local artists Gary Grimshaw and Carl Lundgren, and featured psychedelic light shows just like the Fillmore.

The MC5 went into the recording studio for the first time in March of 1967. The band had hooked up with a new set of managers and they booked the band into United Sound to record a cover of Them’s “I Can Only Give You Everything”. The B-side was an original called “One Of The Guys”; and the single was released on the tiny AMG label. Although their record failed to get airplay or generate sales, the MC5 were developing a reputation at the Grande Ballroom that enabled them to find more paying gigs around the Detroit area. By August of 1967, the band asked John Sinclair to become their manager.

In February of 1968, the MC5 recorded their second single. Both songs, “Looking At You” and the B-side “Borderline”, were originals and the single was released on A-Square Records. Only 500 records were pressed, but “Looking At You” captured the band’s maturing sound and impressed both their fans as well as fellow Detroit musicians.

The Grande Ballroom, meanwhile, had become a successful enterprise that was now booking national acts such as the Who, Cream, the Byrds, and Big Brother and the Holding Company. The MC5 were now enjoying popularity on a much larger scale and took pride in overpowering some of the visiting national acts, like Boston’s Beacon Street Union, and heckling other bands they thought were underperforming by shouting “Kick out the jams” at them from the audience. It wasn’t long before Wayne Kramer and Rob Tyner turned “Kick Out The Jams” into the song that would be the rallying cry for both the MC5 and Detroit rock and roll.

After the Detroit riots of 1967, and because of the drug scene surrounding the emerging hippie movement and John Sinclair’s Trans-Love Energies, there was a greater police presence at any large gathering in or around the Metro area. The MC5 were rapidly becoming political lightning rods for confrontations between the youth culture and law enforcement in well publicized run-ins at the Hideout, the Grande, the Loft in the town of Leonard, Belle Isle in Detroit, and at Ann Arbor’s West Park. In addition, Sinclair was now facing an automatic ten-year sentence for his third arrest on drug charges, this time for passing two free marijuana joints to an undercover police officer.

In spite of these events, or maybe because of them, Sinclair decided that the MC5 should participate in a music festival at Lincoln Park in Chicago during the Democratic National Convention in the summer of 1968.

But when the band arrived, they found that they were the only group to have showed up, all of the others having bowed out due to the bad publicity and the negative vibes surrounding the Democratic Convention. The MC5 played only four or five songs before agitators in the crowd started a disturbance and the police marched in and started clubbing the crowd. The band packed their equipment and left the chaotic scene as quickly as they could.

On a trip to New York to promote the band, John Sinclair met Danny Fields from Elekra Records. Sinclair invited Fields to Michigan to see the MC5 perform live at the Grande Ballroom. Impressed by the show, Fields also took Wayne Kramer’s recommendation to check out the Stooges the next afternoon at the Union Ballroom in Ann Arbor. Fields then called Elektra boss Jac Holtzman and recommended that he sign both bands to the label.

It was decided that the MC5’s debut album on Elektra would be recorded live at the Grande Ballroom. Remote recording equipment was flown in and the MC5 recorded the shows on October 30th and 31st that would become the “Kick Out The Jams” album. On the day after the recordings, Sinclair announced the formation of a new political division of Trans-Love Energies called the White Panther Party.

The MC5 would be the new party’s revolutionary band ready to wage a “total assault on the culture by any means necessary, including rock and roll, dope, and f***ing in the streets”. Unfortunately, this manifesto attracted some very radical groups to the MC5, and they caused the disruption of the band's shows at two very influential East Coast venues, Don Law’s Boston Tea Party and Bill Graham's Fillmore East in New York. The hard feelings brought on by the two incidents caused the MC5 to be blackballed by two of the biggest concert promoters in the country.

Meanwhile the “Kick Out The Jams” album had been released with its infamous “Kick out the jams, motherf******s!” included. It was the first major label release to include the expletive in the grooves and also the first to include the word “f**k” in the liner notes written by John Sinclair. The single of “Kick Out the Jams”, however, was recorded with the words “brothers and sisters” substituted so it could get played on Top 40 radio stations.

The single became a minor hit, peaking at # 82 on Billboard’s Hot 100. The “Kick Out The Jams” album was more successful reaching # 30 on the Billboard chart in 1969, despite the fact that some record store clerks had been arrested for selling an “obscene” album.

In Detroit, Hudson’s department stores refused to stock the record. The MC5 retaliated by putting an ad in an Ann Arbor underground paper that included the statement “F**k Hudson’s!” along with the logo of Elektra Records. Sinclair and the band then had a meeting with their furious label chief, Jac Holtzman, who proposed that Elektra put out a new “Kick Out The Jams” with the “brothers and sisters” version of the title song. The MC5 and Sinclair argued that the label should push the original album and when nothing was decided, the band began what turned out to be a disastrous West Coast swing of shows.

When they returned to Michigan, the MC5 found a stack of newly designed “Kick Out The Jams” albums with the offending liner notes removed and “brothers and sisters” substituted on the title cut. When Sinclair flew to New York to confront Holtzman, the MC5 were abruptly released from their Elektra contract.

Danny Fields then got the MC5 in touch with Jon Landau who was instrumental in getting the band signed to Atlantic Records in 1969. Fields and Landau convinced the band to part ways with John Sinclair shortly before Sinclair went to trial and was sentenced to the mandatory ten years in prison for his third drug offense.

With Landau producing, the MC5 recorded a basic rock and roll album called “Back In The U.S.A.” The album was a major disappointment for Atlantic, reaching only # 137 on the Billboard album chart. Furthermore, the singles “American Ruse” and “Tonight”, that were released from the album, did not chart at all. The radical political activity swirling around the MC5 had tarnished their reputation with the record-buying public. Lost in all the confrontations and rhetoric was the fact that they were a great rock and roll band. Their album was very popular in England, however, and many feel that it provided a blueprint for the British punk rock movement of the late Seventies.

After the commercial failure of “Back In The U.S.A”, the band produced their third album, “High Time” in 1971 along with Geoffrey Haslan. Fred “Sonic” Smith emerged as the MC5’s principal songwriter by contributing four of the eight lengthy songs. The band had learned how to be creative in the studio but it was too late. Despite it being their best record yet, the album did not chart and the band was dropped by Atlantic.

Late in 1971, the MC5 was without a label and falling apart. The band had worked up some fresh material but after a new record deal fell through, the drug problems, money difficulties, and career frustrations combined to bring the MC5 to an end.

December of 1971 saw a large “Free John Sinclair” benefit concert at the Crisler Arena in Ann Arbor that featured Stevie Wonder, Bob Seger, Commander Cody & His Lost Planet Airmen, and special guests John Lennon and Yoko Ono. The MC5 were conspicuous in their absence from the event. Sinclair was released from Jackson Prison on bond three days later.

Wayne Kramer, Michael Davis, and Dennis Thompson are still alive and have reunited in recent years for some MC5-related projects. Rob Tyner died of a heart attack in 1991. Fred “Sonic” Smith formed Sonic’s Rendevous Band in the 1970’s and married rock star Patti Smith. Fred Smith died in 1994 from heart failure. The MC5 was voted into Michigan Rock and Roll Legends Hall of Fame in 2006. In 2008, "Kick Out The Jams" was voted in as one of Michigan's Legendary Songs.

Dr. J. Recommends:

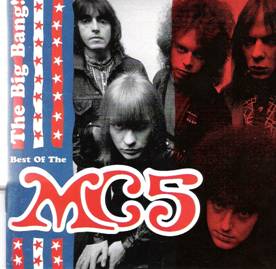

“The Big Bang! The Best Of The MC5”. Rhino Records. This is an excellent 21 track compilation of the MC5 done with the involvement of Wayne Kramer. Besides including the highlights from their three albums, this set includes three early single tracks along with an unreleased live version of “Thunder Express”, one of the songs that would have been part of the band’s never-completed fourth album.

“High Time”. Rhino/Atlantic. If all you’ve heard from the MC5 is “Kick Out The Jams”, this album will surprise you. It’s a great Michigan hard rock recording on which Fred "Sonic" Smith especially shines.

From The Bookshelf

Grit, Noise, And Revolution: The Birth Of Detroit Rock 'N' Roll by David A. Carson. The University Of Michigan Press 2005. This is an outstanding history of the first twenty-five years of Rock and Roll in the state of Michigan. Of all the artists covered in this well-written book, the story of the MC5 is told in the greatest detail. The MC5, of all Michigan bands, has a body of music that is a great fit with the title of this book.