Although he is not a household name in Michigan rock and roll circles, Ollie McLaughlin was an important force in the state’s musical history. He wore many hats in his storied career, including a stint as an influential black disc jockey at WHRV in Ann Arbor, a jazz concert promoter, a talent scout who discovered both Del Shannon and Barbara Lewis, a record producer, a music publisher, and the owner of three important Michigan record labels.

Ollie’s youngest daughter, Moira, wrote about her father’s early family history: “My father was the youngest of 12 children born in Carthage, Mississippi, in 1925. His parents were Georgia and Ira McLaughlin. Ira, who was also known as ‘Mack’, was born in 1855. He was the son of a black slave woman and a white overseer whose last name was McLaughlin and was often referred to as ‘The Irishman’. Ollie’s mother, Georgia, was born in 1881 and was part black and part Choctaw Indian. She resided near an Indian reservation and was 13-years-old when she married Mack.”  Ollie McLaughlin

Ollie McLaughlin

“By the time Ollie was born, most of his older siblings had moved North to Chicago, Illinois, and Grand Rapids, Michigan,” Moira wrote. “Wanting a better life for their son, Mack and Georgia sent Ollie to live with Maxie McLaughlin, one of his older brothers. Maxie and his wife Venie had moved to Ann Arbor and resided in a nice house near the campus of the University of Michigan, and they rented rooms in the upstairs of their home to college students.”

Ollie attended junior high and high school in Ann Arbor and, after graduating, he enrolled in Columbia College in Chicago, where he studied acting. After serving in the Army during World War II, Ollie returned to Ann Arbor and got a job at WHRV-AM as a disc jockey. WHRV, which stood for Huron River Valley, went on the air in 1947. It was an affiliate of ABC, and it was one of the few stations in the United States that was owned by the network. In 1963, along with a change in owners, the station became WAAM - short for Ann Arbor, Michigan.

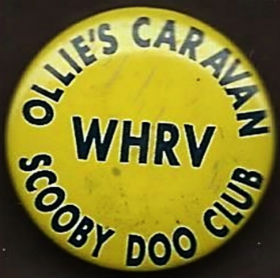

His nightly program, Ollie’s Caravan, became a fixture at WHRV almost as soon as it went on the air in 1952. Eric Carpenter attended the University of Michigan from 1953 through 1957 and was a fan of Ollie’s show. “Ollie had a very special voice,” Carpenter recalled. “He had the perfect voice for a DJ, and he had the kind of program format that played the music that appealed to both the secular and collegiate audience. One of the other unique things about Ollie is that during the daytime he would sell time for the station, not only for his nighttime show, but for the station as a whole. That gave Ollie the chance to get to know just about all of the sponsors for WHRV.”

Ollie was often on the University of Michigan campus promoting concerts and hosting sock hops. Eric Carpenter, who is white, met and became friends with Ollie McLaughlin while attending the U of M. Carpenter graduated from the university's architectural school in 1957. He later did some house designing for Motown artists including Mary Wilson and Florence Ballard of the Supremes, and he also designed Berry Gordy Jr.'s home on Outer Drive in Detroit, before he moved into the Gordy mansion. Carpenter has a wealth of interesting anecdotes centered on his experiences with Motown.

In a recent interview, Carpenter shared some of his memories of Ollie’s radio career. “During the 1950s, Ollie started the Scooby Doo Club,” Carpenter said. “All members got a card that gave the bearer certain perks like discounted prices at stores or coupons to buy one and get one at 1/2 off. Besides being a very talented DJ, Ollie was also a very creative marketer. He was a visionary in the marketing field and cleverly tied his sponsors into the benefits of the Scooby Doo memberships to boost their sales. As a result, he had an audience that included all of the Ann Arbor area.” According to a 1997 newspaper story dealing with the history of WHRV, Ollie’s Scooby Doo Club had over 10,000 members linked to his radio show. The membership simply meant that you listened to Ollie and tried to be nice to others. Corny as it might sound today, it was a big thing among young people in Ann Arbor during the 50s and early 60s.

Dale Leslie, former marketing director of the Ann Arbor Chamber of Commerce, was a big fan of Ollie McLaughlin and a proud member of the Scooby Doo Club. "This was a time when rock and roll first came out and some considered it the devil's music," Leslie recalled during a 1997 interview. "Ollie cut through all that by having this club that you could belong to if you did good deeds and were nice to people. That helped ease some of the fears of adults."

It should be noted that Ollie’s club was established many years prior to, and had nothing to do with, the Scooby-Doo, Where Are You? animated Saturday morning television series, first aired in 1969 by Hanna-Barbera Productions. It’s a little uncertain as to how Ollie McLaughlin came up with his ‘Scooby Doo’ moniker, but his son, Ira, said in a recent phone interview, “It was a saying back then; ‘You’re a real cool Scooby Doo.’ It was my father’s thing that everyone could become a Scooby Doo”.

Sammy Kaplan also met Ollie on the campus of the University of Michigan during the 1950s. “Ollie played rock and roll and took dedications Monday through Friday,” Kaplan recalled. “He had a huge following among the U of M students. Ollie did a lot of one-nighters, record hops, and shows; and he was very popular among his listening audience,” Kaplan said.

Morris Kaplan, Sammy’s father, was in the music business and had started a label called Danceland Records. In 1949, he released one of John Lee Hooker’s earliest recordings, “Wayne County Ramblin’ Blues,” on Danceland under the name ‘Little Pork Chops’. In 1960, Sammy Kaplan would follow his father's footsteps when he formed Lovelane Music Publishing in Detroit.

Ollie McLaughlin was a jazz enthusiast, according to his son Ira. “Jazz was the hip music when my father was growing up in the 1940s,” he said. Because of his love of the genre, Ollie promoted jazz shows in Michigan for a variety of artists. “He was a friend of the dentist who owned WJZZ, the jazz station in Detroit,” Eric Carpenter recalled. “The venues Ollie used were Baker’s Keyboard Lounge in Detroit and Eddie Sarkesian’s jazz club in River Rouge.

It was during this time in the 1950s that Ollie McLaughlin met Ruth Toomes, the love of his life. Moira McLaughlin wrote this about Ruth: “My mother was from Keokuk, Iowa. She attended the University of Iowa for a short time and majored in Library Science. She later moved to Ann Arbor and worked at the library at U of M.”  Ruth Toomes

Ruth Toomes

Although the University of Michigan was considered a progressive school, its policies and the attitudes of the majority of the citizens in Ann Arbor reflected the racial discrimination that was sadly common at the time. “My mother had a difficult time finding housing to her liking because boarding houses and rooms for rent in the nicer areas did not rent to blacks,” Moira wrote. “She did eventually find a place and settled in. While shopping in the market, she met my father for the first time after he approached her and started a conversation.”

“Shortly after that, the woman that rented the room to my mother told her she could no longer live there, and she was asked to move out. Because of my mother’s light complexion, the woman had assumed my mother was white. She accused my mother of lying and trying to pass.” (Passing was a term used in the United States to describe a person of color or multiracial ancestry trying to assimilate into the white majority) “My mother’s response was, ‘I didn’t lie to you. You just never asked.’ My mother never in her life tried to pass. The woman made it clear that she didn’t rent to Negroes, and if she had known in the beginning, she would have never rented to her. She claimed that she thought my mother was Jewish or Hispanic.”

“My mother later learned of Maxie and Venie McLaughlin’s boarding house. As fate would have it, on the day she was moving in, my dad, who had lived there since a teenager, was moving out,” Moira wrote. “They remembered each other from the market and the rest, as they say, is history. They dated and married in 1958. It was a very small ceremony at St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church with Eric Carpenter serving as Best Man.”  Ruth and Ollie McLaughlin

Ruth and Ollie McLaughlin

Eric Carpenter remembered how the racial attitudes in Ann Arbor at that time affected the wedding plans. “Ollie wanted a small wedding because he knew it might very well get complicated with two black families traveling to Ann Arbor during the 1950s and attempting to find lodging that would be open to black guests,” Carpenter recalled.

“He was the only black DJ at WHRV,” Carpenter stated. “Ollie never talked much about the difficulties he must have faced as a black man. I think it was because Ollie didn’t simply view himself as a black man, but as an important human being that had something to contribute. Because of his great amount of self-confidence, he didn’t think about racism. He always felt that people shouldn’t judge him as a great black DJ, but as a great DJ period.”

Sammy Kaplan agreed. “Ollie was a very interesting man,” he said. “He had a great compassion for people, and he was very well liked. Because of his personality, he was able to crossover many years before it became fashionable for blacks to be accepted in white circles. His confidence came from being a nice man who was very gifted and respected by large groups of people during his radio career.”

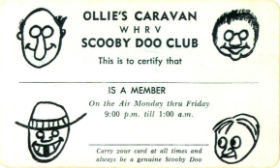

Ollie McLaughlin had passion for the music and artists of the day, and he also had an eye for new talent. “Ollie could sniff out talent”, Carpenter said. “He had an advantage over other producers in that he was a DJ. When you play music five nights per week for a young audience, you develop an ear for both the winners and the losers. He had every opportunity to seek out talent and take advantage of developing it.”  Max Crook, Ollie, and Del Shannon

Max Crook, Ollie, and Del Shannon

His most important talent discovery was Del Shannon. In a 1972 interview dealing with the history of station WHRV, Ollie recounted the events leading to his discovery of Shannon and the recording of his hit song “Runaway”. “Max Crook was a friend of mine who was attending Western Michigan University,” Ollie recalled. “He was playing in a group with Del Shannon and when he came back to Ann Arbor, he mentioned that there was a singer that he wanted me to hear. At first, I put him off because I didn’t want to waste my Saturday and miss a U of M football game. Besides, it was something that I heard all the time – people telling me about a singer, and it had always been a dead end.”

“Finally, I decided to drive over to Battle Creek where Crook and the singer were performing at the HiLo Club and check him out,” Ollie said. “On the drive, I heard a new artist named Roy Orbison on the radio singing “Only The Lonely” – and started thinking that if I could discover someone like Orbison it would be fantastic.”

Ollie made a tape of Shannon performing at the HiLo and brought it to Harry Balk and Irv Micahnik in Detroit, two white businessmen who owned Embee Productions and Twirl Records. Balk had discovered and managed Little Willie John before partnering with Micahnik to form Embee and Twirl. The pair signed Johnny & The Hurricanes, who went on to record several instrumental hits of old tunes with a rock and roll beat on the Big Top label out of New York.  Harry Balk, Del Shannon, and Irv Micahnik

Harry Balk, Del Shannon, and Irv Micahnik

Balk and Micahnik got Shannon a deal with Big Top and took him to New York to record “Runaway”. Although the song is listed as an Embee Production, McLaughlin Publishing did get a piece of the song, which spent 4 weeks at #1 and was honored as the Billboard Song of the Year in 1961. McLaughlin Publishing also got a percentage of some of Shannon’s follow-up singles, including the Top 40 hits on Big Top: “Hats Off To Larry”, “So Long Baby”, and “Hey! Little Girl” along with "Keep Searchin' (We'll Follow The Sun)" and "Stranger In Town" on the Amy label.

“When Ollie began to become successful in record production, he left radio – probably around 1961,” Eric Carpenter recalled. “The more time he spent in the studio, the less time he had for his role as a DJ.” Ollie later went with Del Shannon to England and met the Beatles who were big Shannon fans. Del Shannon became the first artist to chart with a Beatles’ tune in the USA when he released “From Me To You” as a single in the summer of 1963.

Ollie first produced some songs that he issued on his own labels back in the late 1950s. He put out his own composition of “Pajama Party” backed with “Squaw” by Joe Hunter and his Happy Cats on the Omack label. Hunter would go on to become one of the early members of Motown’s studio band, the Funk Brothers. Ollie also released 45s by The Vanguards, Kenny Owens, and Gracie Darnell on his Ruth label, named after his wife.

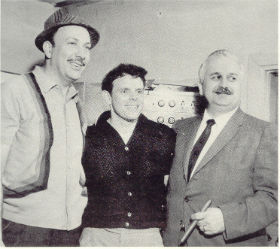

Following the birth of his first daughter in 1960, Ollie christened his new label Karen Records. Barbara Lewis was the first significant artist to record on Karen. According to David A. Carson’s Grit, Noise And Revolution, Lewis was a small-town teenage girl from Salem Township who went to South Lyon High School, located north of Ann Arbor in Washtenaw County. She had been writing songs and singing since the age of nine, and also played guitar, harmonica, and keyboards.

Ollie learned about Barbara from and bandleader friend of her father, and saw potential in a peppy, upbeat tune she called “My Heart Went Do Dat Da”. Ollie took Barbara to Chicago to record the song at the famous Chess Studios. He released “My Heart Went Do Dat Da” in 1961. Ollie promoted the single by booking Barbara Lewis at various record hops around the Motor City and placing the record with numerous radio DJs. As a result, the song received considerable airplay on R&B and Top 40 stations in Detroit, and it became a mild regional hit in the spring.

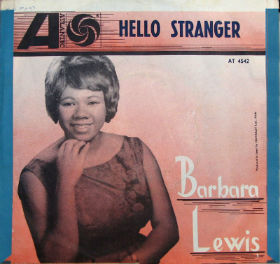

Carson wrote in Grit, Noise and Revolution that for a follow-up, McLaughlin chose another song Barbara had written, called “Hello Stranger”. Lewis, with stylish backing vocals from The Dells, delivered a smooth, warm, and achingly beautiful lead vocal. McLaughlin was so pleased with the outcome that he flew to New York and pitched the recording directly to Atlantic Records, the biggest independent label in the country. After taking the record, Atlantic then held it back for almost a year, deciding that “it was too different.” According to Barbara Lewis, it wasn’t until a competing label had a hit with “Our Day Will Come” by Ruby and the Romantics, that Atlantic decided to release her record.

“Hello Stranger” quickly landed on the charts, going all the way to # 1 on Billboard’s R&B chart and # 3 on the Hot 100 in April of 1963. It was a heady time for a young girl from a rural area north of Ann Arbor. “Ollie McLaughlin took me first class all the way,” Lewis said. “Ollie gave me the same treatment the artists were getting over at Motown. He put me through finishing school and had designer gowns made for me.” Watch a TV performance of "Hello Stranger" by Barbara Lewis

The relationship with Atlantic would prove beneficial to both Lewis and McLaughlin. Barbara would record nine more Hot 100 hits for the label, including the 1965 smashes “Baby I’m Yours” and “Make Me Your Baby”, while Ollie would forge an important national distributorship for releases on his independent Detroit labels.

With all of Barbara Lewis’ singles now being issued on Atlantic, Ollie released a number of non-charting, but excellent, 45s on his Karen label. From 1962 through 1965, Ollie produced a batch of fine R&B singles by The Classics, El Baron, The Capitols, The Antoinetts, Sharon McMahan, Grant Higgins, Rod Jordan, and Matt Lucas.  Sonny Bono, Barbara Lewis, Cher, and Ollie

Sonny Bono, Barbara Lewis, Cher, and Ollie

Ruth McLaughlin had stopped working after she married Ollie. When he entered the music business full time, she often assisted him with the administrative side of the business by typing letters and organizing files. She was also at home taking care of the family which now included their son Ira in 1962, their second daughter Carla in 1963, and their youngest daughter Moira in 1965.

Ollie’s breakthrough single on the Carla label, once again named after a daughter, came in 1966. The artist was Deon Jackson who was born in Ann Arbor. Ollie discovered Jackson while he was still attending Ann Arbor High School and got him signed to a deal with Atlantic Records. Jackson recorded two singles in 1964, “You Said You Loved Me” and "Come Back Baby” that were regional hits in Michigan. After he was dropped by Atlantic, Jackson remained a popular attraction on the teen nightclub circuit before recording his first big hit in late 1965.

McLaughlin took Jackson to the Golden World Studio in Detroit to record Deon’s composition, “Love Makes The World Go ‘Round”. Deon Jackson had attended high school with Ira McLaughlin’s cousin, Bobby, and his name is mentioned along with some of Jackson’s other school friends in the lyrics of his song. The recording features Funk Brothers’ Eddie Willis on guitar, Johnny Griffith on piano, along with Bob Babbitt on bass. Released on the Carla label in January of 1966, the smooth and soulful “Love Makes The World Go ‘Round” was a big hit, reaching # 3 on the Billboard R&B chart and # 11 on Billboard’s Hot 100. Deon Jackson would go on to record two more charting singles on Carla that reached the Hot 100, “Love Takes A Long Time Growing” in 1966 and “Ooh Baby" in 1967.

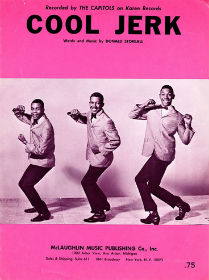

The first smash hit on Ollie’s Karen label came just four months later in 1966. His high energy production of “Cool Jerk” by The Capitols would rocket to # 2 on Billboard’s R&B chart and # 7 on the Hot 100. Ollie had discovered the Detroit R&B trio (drums, guitar, and keyboards) at a local dance headlined by Barbara Lewis and signed them to his Karen label. The Capitols recorded their first single, “Dog And Cat” in 1963, but the group dissolved when their debut failed to chart.

The 1960s saw quite a few dance crazes, and one of the most popular was a dance called ‘the jerk’. It consisted of holding the arms out in different positions and thrusting the hips. It was considered lewd in some circles, especially the sexual version of the dance called ‘the pimp jerk’ that had become popular in Detroit clubs.

Seeking to capitalize on the popularity of the controversial dance, guitarist Don Storball wrote a song about the pimp jerk, renaming it “Cool Jerk” to prevent possible banning by radio stations. Realizing that the song had commercial potential, the Capitols reformed and contacted Ollie McLaughlin to set up studio time. Ollie organized the session at Golden World and again brought in Willis, Griffith, and Babbitt to play on the recording. After “Cool Jerk” became a smash hit for the Capitols in 1966, the group followed it up with two more 45s in the Hot 100 that same year with “I Got To Handle It” and “We Got A Thing That’s In The Groove."

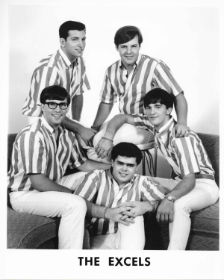

Another one of Ollie McLaughlin’s interesting discoveries was a band called The Excels that had formed in the Upper Peninsula town of Marquette, home of Northern Michigan University. The Excels, who had been making a splash at teen clubs and dances in the northern parts of the state, looked and sounded like the Beach Boys. The young band had traveled to Detroit in the summer of 1965 in search of a recording contract. Motown wasn’t interested, but Smokey Robinson suggested they contact Ollie.

According to Eric Carpenter, “Ollie was different in that it didn’t make any difference whether an artist was black or white.” The Excels found Ollie working at the Golden World Studio and auditioned for him there. Ollie liked the band’s sound and the lead vocals of Clark Sullivan. He advised them to record some demos of their original material and send them to him.

After signing the band in 1966, the Excels went into the studio with Ollie and recorded a Clark Sullivan-penned tune called “Gonna Make You Mine, Girl”. Released on the Carla label, the single was a regional hit in Michigan, hitting # 1 on WSAM’s Super Sound Survey in Saginaw. It was the beginning of a relationship that included five singles by the Excels on Carla and some solo recordings by Sullivan after he left the band in 1969. When members of the Excels were interviewed in 2017 for the band’s MRRL Hall of Fame biography, everyone in the group had fond memories of Ollie McLaughlin as a producer, label owner, and mentor.

During the time he was growing up in Ann Arbor, Ira McLaughlin remembered that Ollie had a lot of parties at the house that included many of the artists that he promoted or recorded. Ira also said that his father used to audition perspective artists in the basement studio in their home. He said that Deon Jackson and the Capitols were at the house very often and that Harry Balk and Irv Micahnik would also stop by.

Ira also said that he and his sisters would sometimes go with Ollie to his recording sessions. By 1967, his office was in the same building as Tera Shirma Studios, founded by Ralph Terrana on Livernois in Detroit. Terrana had been in Detroit bands since he was 11-years-old, the most important being The Sunliners, who later became famous as Rare Earth. In late 1965, Terrana became a partner in the Rainbow Recording Studio. He and fellow investor Al Sherman would soon buy out the other partners and rename the facility ‘Tera Shirma’ – a variation of their last names. Tera Shirma Studio

Tera Shirma Studio

The studio on Livernois was used by Ollie for many of his recordings, and he leased office space in Studio A after Tera Shirma's offices were moved next door to the newly built Studio B. The family would drive to Detroit and the kids would play in Ollie’s office while he was doing sessions. Ira recalled that Sharon McMahan was Ollie’s secretary as well as a songwriter and a recording artist, and sometimes she would take the children into the studio while their father was producing his latest record.

When Ollie recorded at other studios, he usually just brought Ira with him. Ira didn’t remember the names of the studios since he was just 5-years-old, but he recalled that his job was to carry his father’s thermos. Ira also said that he and his sisters were trained to answer the phone and take messages at the McLaughlin home.

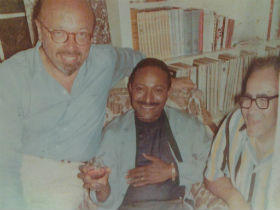

Ollie had a solid professional relationship with Atlantic Records, and the label’s Atco subsidiary was the national distributor for his records. Ira said that his father was close to Ahmet Ertegun, but that Ollie’s main contact at Atlantic was Jerry Wexler. Ira recalled that Ollie and Ruth used to spend time on the East Coast with Wexler and his first wife Shirley. Moira McLaughlin wrote that Jerry and Shirley Wexler were her godparents.  Ahmet Ertegun, Ollie, Jerry Wexler

Ahmet Ertegun, Ollie, Jerry Wexler

Things were looking bright for Ollie McLaughlin in 1967. His labels were producing hits and he hired Al Abrams Associates to handle public relations. Abrams had been with Motown since its earliest days and had been a big part of the company’s rise to national prominence.

Despite the rosy outlook, the sales of his terrific Karen releases were disappointing in 1967. The Capitols failed to build on their success of the previous year, as none of their four 1967 singles managed to chart. Neither did the two great singles by the Soul Twins.

Meanwhile on Carla, the only single that charted during 1967 was Deon Jackson’s smooth and soulful “Ooh Baby”. The previous 11 months saw non-charting records issued by the Four Pros, the Excels, Jimmy Delphs, Kelly Michaels, and the Four Brothers.

In 1968, Ollie established the Moira label, named after his youngest daughter. Three 45s were issued during the label’s first year, including non-charting singles by Jimmy (Soul) Clark and The Firestones, and the funky instrumental “Jan Jan” by The Fabulous Counts, which reached # 42 on the Billboard R&B chart.

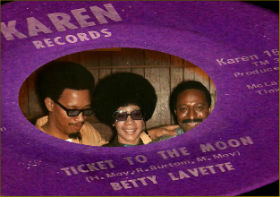

Ollie released nine singles on the Karen label in 1968, including two non-charting singles by new signee Betty LaVette and two more by the Capitols, who were struggling to find another hit like “Cool Jerk”. Jimmy Delph’s “Don’t Sign The Paper Baby (I Want You Back)” was the only charting single on Karen, peaking at # 29 on Billboard’s R&B chart and # 96 on the Hot 100 in the spring. Ollie also released five non-charting singles on Carla, including two by Deon Jackson, and one each by the Excels, Jimmy Delph, and Milton Wright and the Tera Shirma Strings.

The shortage of hits might explain the reduction of singles released on Ollie’s three labels, starting in 1969. Karen Records issued six singles that year including two by Betty LaVette and the Capitols, along with 45s by Marvin Sims and Jimmy Delphs. A cover of “Hello Stranger” by Riley Hampton was the only release on Carla that year. Three singles were issued on his Moira label by the Fabulous Counts, Jimmy (Soul) Clark, and Belita Woods; but nothing Ollie released that year dented the charts.  Dale Warren, Bettye LaVette and Ollie

Dale Warren, Bettye LaVette and Ollie

In 1970, Ollie moved his family to a house on Outer Drive in Detroit. The music scene was in the Motor City, and because the freeways that now connect Ann Arbor and Detroit were not yet built, it took Ollie a good deal of time each day to drive two-lane Plymouth Road into the city and back.

Moira McLaughlin shared her memories of the house on Outer Drive: “The house had a full basement which my father used as an office and mini studio. I remember whenever he was working on a song, he’d play it for us kids and ask us to dance to it. He loved to see us get into the groove of the music. I remember how his face would light up when he’d see us catch the beat. This was his way of determining if the song had the potential of becoming a hit.”

“One of my fondest memories of my dad was every New Year’s Eve he would make shrimp fried rice and the whole family would watch Dick Clark’s New Year’s Rocking Eve,” Moira wrote. “We would get so excited because he let us have a sip of champagne as we’d watch the ball drop.”  Ruth and Ollie McLaughlin

Ruth and Ollie McLaughlin

“In addition to his love of music, my father was an avid sports fan,” Moira recalled. “He and his brother Maxie would often attend University of Michigan football games together. He was also a big fan of the Detroit Tigers. He attended games regularly, and he and my mother were very good friends with the late radio announcer Ernie Harwell and his wife LuLu.”

Ollie had started working with Enterprise Records in 1969 with Clark Sullivan’s first solo single. The Enterprise label was a subsidiary of Stax-Volt Records and, like its parent labels, distributed by Atlantic. Ollie also produced "The Many Grooves Of Barbara Lewis" album and both sides of her first Enterprise single, "Just The Way You Are Today" and "You Made Me A Woman."

In the meantime, the releases on his three labels had dwindled. A single by the Volumes was the only release on Karen in 1970, and the sole release on Carla was a single by the Excels that had been recorded back in 1966, but at that time was not considered good enough to issue. Moira Records released its final two singles that year: a 45 by Belita Woods and “Get Down People” by the Fabulous Counts that would prove to be Ollie’s final charting hit when it peaked at # 32 on Billboard’s R&B chart in the spring of 1970.

From 1971 to 1974 only a handful of singles were issued by Ollie. “Most of the records that my father recorded in Detroit included members of the Funk Brothers”, Ira McLaughlin recalled. “He was friends with Berry Gordy, but when Motown left Detroit, it affected the entire city and led to the decline of the music scene. My father never shut down the labels. He just didn’t record as much. He was looking for talent but didn’t find what he was looking for,” Ira said.

“The decline of his record sales contributed to Ollie’s financial problems,” Sammy Kaplan stated. “In terms of the creative cycle of life, some people are able to continue to have success during their life. There are other people who have success and sometimes aren’t able to maintain that success for whatever reasons. In the creative format, there is a lot of frustration involving having and then not having success."

According to Eric Carpenter, Ollie McLaughlin’s financial problems started in the 1970s. “Ollie knew how a buck could be made and was savvy enough about the business to know how to take advantage of it. McLaughlin Publishing was an example of how versatile he was,” Carpenter said. “But Ollie always thought of the now rather than the future. His financial problems were an example of this,” Carpenter stated.

In order to help make ends meet, Ollie sold some of the publishing rights to some of his songs. Eric Carpenter said this about the deals: “It was an example of how Ollie could also make some bad business decisions. But not many people realized how valuable the publishing on those R&B songs from the 60s and 70s would be in the future.”  Sammy Kaplan of Loveland Music

Sammy Kaplan of Loveland Music

“When Ollie started to have financial problems and it became clear that he needed money, he had an option to sell some portions of his publishing over the years,” Sammy Kaplan stated. “Hello Stranger” is a good example of how Ollie’s classic recordings have retained their value. Kaplan, who moved his Lovelane Music Publishing to Los Angeles in 1971, purchased the rights to “Hello Stranger” during the 1970s when Ollie was having financial difficulties. That publishing is still valuable. Barbara Lewis’ classic recording was used in the film, Moonlight, that won the 2017 Oscar for Best Picture; and in 2018, “Hello Stranger” was featured in a major television advertisement for Amazon.

Ira McLaughlin said that his mother took a job during the family financial crisis. “She began working for a magazine company and eventually moved into a management position,” Ira said. “She stayed with the company for twenty-five years until her health deteriorated.”

Ira revealed that Ollie suffered from diabetes. “I recall him taking his insulin shot every morning,” Ira said. “It was Karen’s job to give him his insulin shot in his belly. The diabetes eventually led to his heart problem.”

“He had a heart attack while shoveling snow but didn’t realize it,” Ira recalled. “He just thought that he wasn’t feeling well, but he still went out and played poker that night with his friends. When he came home and felt worse, he asked to be taken to the hospital, and he was admitted to the Sinai Hospital on Outer Drive. It was there that it was discovered that he had suffered the heart attack the previous day. He was in the hospital for a week and I flew back from New York to visit him,” Ira remembered. “Upon returning to New York, I got a call from my mother that my father had suffered another heart attack and died.” Moira McLaughlin and Eric Carpenter

Moira McLaughlin and Eric Carpenter

“Near the end of his life, Ollie was in dire financial straits,” Eric Carpenter recalled. “I was always loaning him money. It was sad the way he ended up.” Shortly before his death at the age of fifty-eight in 1984, Ollie was working on the release of an album of gospel music by a group called the McAllisters, along with a record project with Carpenter for a group that was doing a resurgence of the Three Stooges and slapstick comedy. While Ollie was in the hospital, Carpenter promised him that he would serve as a mentor for his children in case he passed. Over the years, Carpenter became ‘Uncle Eric’ to the children and a brother to Ruth before she passed away.

“Eric was always in the picture,” Ira recalled. “He and my mother and father were great friends, and my mother continued the friendship after Ollie’s death until she passed away from cancer in 2010.” Eric Carpenter spoke at both Ollie’s and Ruth’s funerals.

Ira McLaughlin was the only one of Ollie’s children to go into the music business. Ollie’s connections with Atlantic Records helped Ira land a job in 1981 at the storied label’s library of recordings in New York. Ira later moved into engineering for the company and worked with many well-known artists over the years including the Rolling Stones, the Bee Gees, Whitney Houston, and Luther Vandross. He returned to Detroit after his mother became very ill and has lived there ever since. Daughters Karen, Carla, and Moira, the namesakes of Ollie’s most famous record labels, are all well. Karen and Carla live in Detroit and Moira lives in New York City.

Because of his many accomplishments in Michigan music, Ollie McLaughlin was named an Honorary Inductee to the Michigan Rock and Roll Legends Internet Hall of Fame in 2018. “He had a tremendous ear for commercial music, as seen in his major discoveries as well as the releases on his own labels,” Sammy Kaplan stated. “He created an American treasure of music that lives on.”

Sources: Moira McLaughlin, Eric Carpenter, Ira McLaughlin, Sammy Kaplan, and David A. Carson's Grit, Noise and Revolution.