by Alina Simone with Gary Johnson

Alina Simone’s Madonnaland, was selected by Rolling Stone magazine as one of the Top Ten Music Books of 2016. It was also the very best Michigan rock and roll book of that year as it examined fame and its aftermath through the stories of its three main subjects: Madonna the most successful female recording artist in history; Question Mark and the Mysterians, a Mexican-American band known around the world for their # 1 hit “96 Tears”; and the Flying Wedge, a here-to-fore unknown band, that recorded one of the Michigan’s most mysterious and collectible 45s in 1972.

Simone’s account of the reluctance of Madonna’s hometown, Bay City, Michigan, to appropriately recognize one of the world’s most famous women and the reasons behind it is fascinating. The same goes for the city’s continued acceptance of a little-known song with racially insensitive lyrics as its official anthem rather than the chart-topping hit that was both written and recorded in Bay City in 1966.

But according to the reviewer in the New York Times, the highlight of Madonnaland was the final chapter which documented the author’s doggedness in pursuing the unusual story of one of Michigan rock and roll’s most curious recordings. Because of her persistence and ability to track down leads, Simone was finally able to get a handle on the four-decade-long mystery of the Flying Wedge; and her detective work would help lead to the rerelease of the band's rare single in 2017.

Alina Simone was born in the part of Russia now known as the Ukraine. She came to the United States at a young age as the daughter of political refugees from the Soviet Union and was raised and educated in Massachusetts.

She started her career as a singer and made several well-received recordings in what might best be described as the alternative-folk category. Although the majority of her recorded output consisted of original compositions, Alina achieved a new level of prominence with the 2008 release of “Everyone Is Crying Out To Me, Beware”, a collection of songs by the late Russian singer/songwriter, Yanka Dyagileva.

Now residing in New York City with her husband and young daughter, Simone began her transition from music to writing with the publication of her first book, You Must Go And Win, in 2011. This was followed by her first novel, Note To Self, in 2013.

Prior to the release of Madonnaland in 2016, Alina’s writings on a variety of topics appeared in the New York Times, New York Times Magazine, Slate, The Wall Street Journal, Guardian Long Read, and she became a regular contributor to Public Radio International’s The World.

Because we had worked together on the sections that dealt with Madonna and Question Mark and the Mysterians, Alina was kind enough to refer to me as her “favorite rock-based detective” in her latest book.

I realize, of course, that I’m not even close to being in the same league when it comes to the kind of investigative reporting she has done for the above publications and PRI, and especially for the final chapter/essay of Madonnaland. That being said, I do know that sometimes a potentially great story pops up when you least expect it, and this is precisely how Alina first learned of the Flying Wedge.

“It started when I was down in Nashville with my friend Allyson to interview Ben Blackwell, supervisor of vinyl production at Jack White’s Third Man Records, for a story that ultimately went nowhere”, Alina wrote. “Ben grew up in Detroit and for seven years ran his own label, Cass Records, which he launched from the bedroom of his childhood home after dropping out of college."

"During the course of our interview he happened to mention he was an avid collector of Michigan rock, especially rare vinyl. So I told Blackwell that I was heading up to Michigan to interview Question Mark and the Mysterians in a few weeks and, on a whim, asked if there were any rock ‘n’ roll stories – perhaps a great mystery in the vein of Searching for Sugar Man and A Band Called Death – still lurking in the Motor City. Ben considered this question for what seemed like a long time. Then he said two words: Flying Wedge.”  Ben Blackwell

Ben Blackwell

After writing the two words on her hand, she returned to New York and attempted to find out more about the Flying Wedge on the internet. After discovering that most of the scant online information about the band came from interviews with Blackwell himself, she sent him an email requesting more information. “Flying Wedge’s output,” he replied, “consisted of a lone self-released 7-inch, heavily sweated by collectors.”

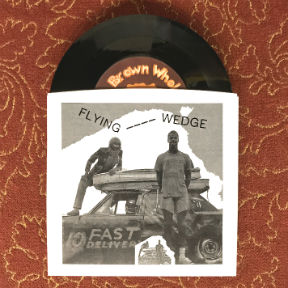

“The gist of the story according to Blackwell was this,” Alina wrote. “Sometime in 1972, a bunch of very young black guys walked into the offices of CREEM magazine and handed then-editor Ben Edmonds their newly pressed single. They didn’t leave their names, nor was there any information about the band on the record itself save for the names of the songs – “I Can’t Believe” and “Come To My Casbah” – and the name of the label, Brown Whole Jams."

"Edmonds took the record home and played it; what he heard blew his mind. But with scant information about the band or the record, he had nothing to write about. So he gave the record to his housemate, Dan Carlyle, a DJ with an evening show on WABX, Detroit’s underground rock FM station. Like Edmonds, Carlyle was stunned by the two tracks and immediately declared the band the Black Stooges.”  Ben Edmonds

Ben Edmonds

Blackwell told Alina that Dan Carlyle played the Flying Wedge record every night for a week, each time beseeching the band and anyone in his audience who knew them to call him. The phone never rang and Carlyle stopped playing the record.

Not long after, Ben Edmonds’ only copy of the single disappeared from the WABX library. As a result, Edmonds spent the next forty years searching local record shops for a copy of the mysterious 7-inch and asking vinyl collectors if they’d ever heard of the Flying Wedge.

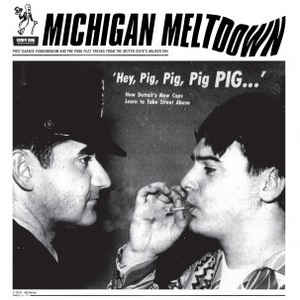

Edmonds was never able to find another copy of the Flying Wedge single or any mention of the band until 2011, when his friend Ben Blackwell sent him a copy of a vinyl compilation of rare Michigan rock called “Michigan Meltdown (Post-Garage Pandemonium And Pre-Punk Fuzz Freaks From The Mitten State’s Miliken Era”.

The misspelled name in the subtitle referred to William G. Milliken who served as Michigan’s governor from 1969 to 1983. The album was released on Coney Dog Records and contained obscure tracks from little-known bands like Insanity’s Horse, Robert Starks and the Geniuses, Tribal Sinfonia, Master Danse, and, lo and behold, both sides of the Flying Wedge single.  Michigan Meltdown LP

Michigan Meltdown LP

Strangely enough, Blackwell had no idea that Edmonds had been searching all those years for the Flying Wedge songs and had actually met the band when he sent him the album. “Blackwell had first learned of Flying Wedge from another collector of rare Michigan vinyl, Brad Hales, owner of Peoples Records in Detroit,” Simone wrote. “It was at a party at Hale’s place sometime in 2010 that Blackwell had pulled the Flying Wedge single out of a box. The artwork on the label was what attracted him at first.”

Blackwell described the label as looking like something a teenager might have drawn in a spiral notebook, but was immediately struck by how eerily unplaceable the music was when he played the record. The songs sounded like they could have been recorded in the 60s, 70s, or 80s. “These were the kind of records that excited him the most,” he revealed to Simone, “the ones that sounded as though they’d been made in a vacuum.” Listen to "I Can't Believe" by Flying Wedge:

The fact that Brad Hales had a copy of the Flying Wedge single is not surprising. According to the Metro Times, Peoples Records is known around the world as a key spot for record hunters looking for rare soul, gospel, R&B, and rock 45s, LPs, and even 78s.

Now with two locations in Detroit, Peoples has been listed in Rolling Stone as one of The Best Record Stores In The USA. The magazine praised the Peoples' stock of secondhand recordings that "spans every esoteric strain from the Twenties to the Eighties."  Peoples Records

Peoples Records

What made the Flying Wedge so fascinating to Hales, Edmonds, and Blackwell was the fact that they were thought to be a band of young black musicians playing heavy rock in both an era and city where Motown still reigned supreme.

They were not the only ones however. George Clinton and Parliament/Funkadelic, a funk, soul, and rock collective, had forged an alliance with Detroit’s rock scene and went on to achieve thirteen top ten hits on the American R&B charts between 1967 and 1983, including six number one singles. Two other black Detroit bands, Black Merda and Death, also recorded rock albums but were unable or unwilling to do the things necessary to reach a larger audience.

Not satisfied that she had uncovered the whole story, Alina Simone went back to Ben Edmonds for another interview in the hope that she might get a clue as to how to locate any surviving members of the Flying Wedge. At the time, Edmonds was working as the US correspondent to MOJO magazine, but unbeknownst to Alina, he had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and would pass away the following year in March of 2016, the same month that Madonnaland was published.

In what would prove to be some of his final thoughts on the Flying Wedge single, Edmonds had this to say to Alina: “It seemed to me like they were messing around with rock ‘n’ roll ideas that were a little more pure than Black Merda, or Death, or Parliament/Funkadelic for that matter. It was the best piece of noise I had heard in quite a while, especially coming from such an unlikely source. The kids were kind of shy and looking around, and they kind of pushed the record toward me and then were gone. I don’t really remember talking to them about anything. But when I listened to it, I heard just this wonderful, wonderful rock ‘n’ roll noise.” Listen to: "Come To My Casbah" by Flying Wedge:

In a later email to Alina, he clarified his earlier statement that the Flying Wedge single would have been interesting wherever it came from. “Of course the truth is that it was of interest primarily because it was a black record. A black record that didn’t appear to contain any of the customary black music reference points. It was obviously infused with rock & roll energy, but wasn’t aping anything on the rock side either. This is where the Stooges comparison comes in. The Stooges invented themselves out of nothing, rock’s first DIY story. Though the drummer of Flying Wedge has obviously had some experience, the overall sound is of a band inventing itself on the spot.”

Despite having Edmonds caution her to not read too much into the significance of the Flying Wedge, Alina remained hooked on the idea of locating the band. Because we had worked together on material for Madonnaland, she emailed me asking if I knew anything about the Flying Wedge and its single. I had not heard of the band at that point and could only offer a feeble suggestion to check with Detroit’s Archer Record Pressing facility to see if the seven-inch might have been pressed there.  Brad Hales

Brad Hales

Alina discovered that Ben Blackwell had already checked the Archer archives and found nothing on the Flying Wedge; and she also realized that he had been holding out on her when he revealed that he had previously known that the QCA (Queen City Album) pressing plant in Cincinnati did some work for other releases on the Brown Whole Jams label.

He then passed on this bombshell to Alina: “A few months ago, Brad Hales had told Blackwell that a guy walked into Peoples Records and mentioned he was once a member of Flying Wedge. The guy promised to come back to the shop and consign some Flying Wedge singles, but never did.”

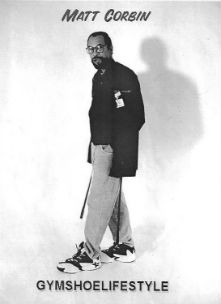

After contacting QCA president Jim Boskin, she discovered that the company had no record of pressing the Flying Wedge single from 1972, but it had done three jobs for the Brown Whole Jams label in 1982. All of the orders had been made by Greg Corbin, with a Detroit address. She called Brad Hales to ask if it was Greg Corbin who had come into Peoples Records, but Hales informed her that Greg Corbin was dead, and that it was his brother, Matt, who had come by his shop and had also left his card containing his contact information. Eureka!  Matt Corbin

Matt Corbin

Although there was very little online information about Flying Wedge other than the Youtube videos for “I Can’t Believe” uploaded in 2012 and “Come To My Casbah” uploaded in 2014, Alina found that there was quite a bit about Matt Corbin.

Essay’d, a site that features short essays on Detroit artists, featured a piece on Matt Corbin by Steve Panton. In it, Panton wrote that Corbin worked at the Children’s Museum in Detroit, creating exhibits, displays and lesson plans; and that led to an offer to teach art in Detroit Public Schools. From there, he eventually landed “a dream job of teaching twice daily open-ended studio classes in Commercial Art to creatively gifted kids from throughout the city.”

Corbin sounds like a very interesting teacher. Panton wrote that Corbin developed a performance piece for one of his high school classes called “Gymshoelifestyle” wherein “he built on his students’ footwear fixation by wearing size 22 gym shoes to class to make a gently humorous point about the absurdity of consumer society, and how to subvert this to carry your own message.”

The essay also went into detail on Corbin’s own style of art which is centered on the found object assemblages he had been making for almost four decades near his home at Clairmount and Woodward in Detroit. The most imposing of these public art structures is the 30 foot tall metal sculpture called Geome Tree, a 1987 work done in collaboration with artist Richard Bennett. There was no mention in the essay of Corbin’s music career, however.  Corbin's Geome Tree

Corbin's Geome Tree

Alina traveled to Detroit to interview Matt Corbin in his home. She learned that Matt and his younger brother Greg were born in Pittsburgh but grew up in northwest Detroit in a solid middle class family. Although neither of their parents were musical, they provided music lessons for their sons, Matt on clarinet and Greg on guitar.

The brothers started playing together informally while Greg was still in high school, but they got much more serious when Greg rejoined Matt in Detroit in the late 60s after earning a degree in biology at Tennessee State University.

Matt told Alina that they called their band Penn Dixie. He said Greg was influenced by both Jimi Hendrix and jazz guitarist Charlie Byrd while he was inspired by horn player Eddie Harris. Matt did the lead vocals and played his clarinet through electronic gear that allowed him to get a variety of sounds from his instrument.

The band was rounded out with Elwin Rutledge on keyboards and Vic Hill on drums. “Soon they were getting gigs at colorful hotspots like Frantic Ernie Durham’s Ballroom on Fenkell Street, the Roostertail, down by the waterfront, and the hippie hangouts lining Plum Street,” Alina wrote.

Although the Flying Wedge single sounded to Ben Blackwell like it was “made in a vacuum”, Alina discovered that the opposite was true. There was black rock in Detroit during the time that Penn Dixie was playing the club scene, and it included Black Merda and Death.

To cut costs, the band rented the house of Clairmount and Woodward as both a dwelling and a rehearsal space. Matt Corbin told Alina that although Penn Dixie never released a record, they did make a number of recordings at both Artie Field’s studio that was within walking distance of the house on Clairmount and also at the legendary United Sound studio.

Matt Corbin also revealed to Alina that Penn Dixie attracted some interest from major record labels. The most interesting of these was Motown, which sent famed producer Harvey Fuqua to see the band play. Fuqua, whose background was in doo wop and the type of pop soul that was Motown’s trademark, seemed an odd choice to evaluate the band.

Barney Ales had recently convinced Berry Gordy to start a rock-oriented subsidiary called Rare Earth to attract the post-Woodstock white record buyers who were more apt to buy albums than singles. The Rare Earth label, which had a great deal of commercial success with its namesake band, Rare Earth, and had signed a number of other Detroit rock acts such as the Sunday Funnies, SRC, and Stoney & Meatloaf, would have been a more likely landing spot for the experimental black rock of Penn Dixie than any of Motown’s renowned soul music labels.

Nothing came to fruition, however, and without a record label and the owner of the house on Clairmount announcing he was selling, the band splintered. Matt, who was working as a public school art teacher, and Greg who had a job as a building inspector for the city of Detroit, ended up buying the house and dividing it into a duplex.

At this point in 1972, Matt got married, started a family, and began to put more energy into his art career. Greg, in the meantime, took all of the Penn Dixie archive to his part of the house and used it as part of his new solo project called Flying Wedge.

It’s now clear that when Matt Corbin stopped by Peoples Records and told Brad Hales that he was once a member of Flying Wedge, his statement was only partially true. Matt told Alina that sometimes his brother asked him to write some lyrics for whatever music he was working on, including a couple of releases issued under the moniker Miraculous. But Matt admitted that he really didn’t know how the Flying Wedge single was recorded, sometimes claiming that the songs were recorded in a studio and other times that all or most might have been done in Greg’s part of the house on Clairmount. He was equally sketchy about who might have played on the Flying Wedge single or who might have accompanied his brother to the CREEM offices to drop off the copy to Ben Edmonds.  Gibson Flying G

Gibson Flying G

Trying to recall events that had happened over forty years prior is probably the reason that Matt Corbin's memories seem to be a little shakey. He informed Alina that he and Greg started leaning in a harder, more experiemental direction after stumbling onto the Isley Brother's 1962 hit single "Twist and Shout", specifically the B-side, a song called 'The Spanish Twist' that he said "featured Jimi Hendrix's electric guitar in place of a vocal line."

Hendrix did not play on the song, however, and didn't join the Isley Brothers' band until eighteen months after its release in 1962. Hendrix's first recording with the Isley Brothers was "Testify Pts 1 & 2", released in June of 1964.

Then there was the band name. Matt told Alina that the Flying Wedge name was inspired by Gibson’s famous Flying G guitar, but he couldn’t recall if his brother even owned one of the guitars. The Gibson Flying G is a very distinctive guitar; and one that would stand out in just about any situation. It was first introduced in 1958, and Albert King and Lonnie Mack were two of the early guitarists who used the model for live appearances and on their recordings.

In the 1960s, Dave Davies of the Kinks was one of the few artists using a Flying G because by that time the guitar was out of issue due to lack of commercial success. In the 1980s, the Flying G underwent a comeback when it became a popular heavy metal guitar because of its aggressive, futuristic look and the fact that it was used by some of the genre’s top guitarists including James Hetfield and Kirk Hammett of Metallica. Kawai/Kingston Flying Wedge

Kawai/Kingston Flying Wedge

Because of the relative unavailability of the Flying G during the late 1960s and 1970s and the fact that I couldn’t find a single instance in which the Flying G was ever referred to as a “Flying Wedge”, I couldn't help but wonder if Matt Corbin was incorrect in stating that it was the inspiration for his brother.

It might be entirely possible that the name for Greg Corbin’s solo project was taken instead from the 1968 Kawai/Kingston Flying Wedge guitar – one of the coolest and most bizarre of all Japanese guitars from the late 1960s. The advertising blurb for the guitar went like this: “New Flying Wedge. The hit of the season. Large solid body. Exclusive guaranteed adjustable Canadian maple neck. Inlaid rosewood fingerboard. Adjustable bridge. Hard lacquer finish provides durable protection. 20 frets. Tone and volume control, two pickups w/tremolo.”

The price for a new Flying Wedge guitar back in 1968 was just $54, and its appearance in the marketplace fits nicely into the Penn Dixie/Flying Wedge timeline. Because of their low price and the fact that they looked rather unique, these Japanese guitars were able to find a share of the market back in the day and are still considered to be of interest, especially to collectors of oddball guitars.

Dan Auerbach of the Black Keys purchased a vintage Flying Wedge guitar online and had it customized to his specifications. He played it with his side-project, The Arcs, for the band’s 2015 national television debut on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert.  Dan Auerbach's Flying Wedge

Dan Auerbach's Flying Wedge

Much of the mystery that still surrounds Flying Wedge has much to do with the secretive nature of Greg Corbin. After the breakup of Penn Dixie, he didn’t share much about what he was up to musically with his brother. Matt told Alina that Greg even kept his liver cancer hidden from his brother. Matt only learned of his brother’s illness when one of Greg’s lady friends called and asked why he was in the hospital.

Even then, Greg insisted that Matt keep his failing health secret from the rest of their family. It was only when his cancer became terminal that Greg moved in with their mother, who nursed him until the end of his life.

Matt revealed to Alina that his brother “thought playing guitar was the coolest thing you could do. And that’s what he wanted to do. And that’s what he did.” He also disclosed that since Greg’s death in 2000, his side of the house had been untouched and that it contained the Penn Dixie material, boxes of the rare Flying Wedge single and other releases on his Brown Whole Jams label, including the Miraculous material.

It also contains Greg’s TEAC tape machine and the solo tapes he made over the years, along with his artwork, notebooks, and even footage from an unfinished music video. But despite interest from reissue labels like Third Man Records in Detroit and the Numero Group in Chicago and his own expressed interest in seeing his brother’s music released, Matt had yet to undertake a thorough review of the material by the time that Madondaland went to press.  Flying Wedge single

Flying Wedge single

Eleven months later, the Numero Group and Third Man Records were able to reach an agreement with Matt Corbin, and 200 vinyl copies of the Flying Wedge single were rereleased by Numero in conjunction with Third Man Records and were available only at Third Man’s Cass Corridor location on April 15, 2017.

The Chicago-based indie record label has 325 releases under its belt — many of which celebrate rare, historical and local music that Numero Group has purchased and otherwise wouldn’t be heard or made available, including obscure Detroit releases by the Burnett Sisters and LaVice & Co. that could also be purchased at Third Man on April 15th.

Numero Group has received seven Grammy nominations for the packaging of its releases, which often include rare archival photos and additional details about the music. Whether the label’s future releases will include any other music from the Greg Corbin archives remains to be seen.

For a more in-depth look at Alina Simone's "revelatory road trip through the quirky hinterlands of celebrity and fandom and the quest to make music that matters in the face of relentless commercialism," read Madonnaland.

Main Sources:

Madonnaland by Alina Simone, University of Texas Press, 2016.

30 Matt Corbin by Steve Panton, Essay'd, September 1, 2015.

Numero Group Brings Rare Detroit Music To Third Man by Ryan Patrick Hooper, Detroit Free Press, April 13, 2017.

Dan Auerbach Launches The Rocket by Tim Perlich, The Perlich Post, October 2, 2015.