When Frankie Lymon died from a heroin overdose in 1968, he was broke and trying again for a comeback that he never achieved. He left no fortune, but his name was listed as one of the songwriters of “Why Do Fools Fall In Love”. It was the hit that made him and the Teenagers famous back in 1956, and the one song that he recorded that remained both popular and valuable over the years.

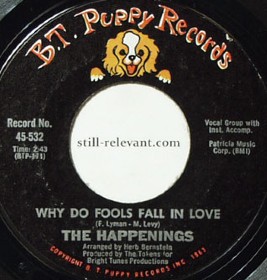

During 1965, the copyright for “Why Do Fools Fall In Love” was changed. The names of Frankie Lymon and Morris Levy were now listed as the songwriters. Levy was the head of Roulette Records, the independent label that bought out the Gee label which originally released the record. Back in 1956, the hit song had first been credited to Frankie Lymon, Herman Santiago, and George Goldner - head of Gee Records. It was modified to just Lymon and Goldner on subsquent recordings for the next decade before Goldner's name was replaced by Levy's. Most record buyers did not become aware of this latest change until the Happenings recorded a cover version of "Why Do Fools Fall In Love" in 1967 with Levy's name listed on the label.  The Happenings' 45

The Happenings' 45

In 1984, as the original copyright term of “Why Do Fools Fall In Love” was expiring, Emira Eagle Lymon brought suit in the U.S. District Court in New York against Morris Levy, his record label, and his publishing company. Her complaint charged fraud, misappropriation and copyright infringement, among other offenses. She attempted to recover all the royalties from the date of the record’s release because she alleged that neither Levy nor his predecessor as co-writer, George Goldner who discovered and recorded the Teenagers, was actually a songwriter.

The resulting trial was fascinating look into Frankie Lymon’s post-stardom personal life, and it was covered in great detail by Washington Post reporter Paula Span. Her published account of the trial and the three women contesting to be named Frankie’s legal wife and heir was titled The Three Wives: The Legacy Of Love.

Back in the 1950s, when a star-struck group like the Teenagers finally got to audition for the head of a record company, such matters as copyright barely figured in the conversation. “Kids didn’t know about royalties” said Bob Hyde of Murray Hill Records. “They wanted to impress their friends in school by being on the radio."

Like the jazz and blues artists before them, the rock and rollers of the 1950s and 1960s were often ripe for rip-offs, and royalties were underestimated or simply never paid. Recording costs and commissions for everyone from managers to choreographers could siphon off much of a group’s earnings. It was also not uncommon for an agent, producer, or record label head to name himself co-writer of a group’s songs, thereby entitling him to half of the author’s publishing royalties.  Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers

Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers

Owning the rights to 1950’s rock and roll songs meant more in the 1980s than it did when they were hits. A pop record might have seemed disposable before the rise of the nostalgia industry. No one could have foreseen that the people who grew up with the music would refuse to relinquish it, and the songs would be repeatedly recycled into movie soundtracks and albums, cover versions, oldies compilations, and television commercials. “Why Do Fools Fall In Love” was a prime example, and its publishing rights may have earned a lot of money by 1984, according to Chuck Rubin of Artists Rights Enforcement Corp.

Rubin established his organization in 1981 to represent artists who he believed had been deprived of their earnings by their record companies. Artist Rights Enforcement Corporation was heralded by the New York Times as “the white knight of rock ‘n roll” for its efforts in recovering uncollected royalties for a host of artists including Wilbert Harrison, Richard Berry, the Coasters, and the Dell Vikings to name just a few.

It was Rubin who, several years earlier, came to the conclusion that Lymon’s estate was not receiving appropriate royalties. He then located Emira, put her in touch with an attorney, and helped line up witnesses and documentation.

Her adversary, Morris Levy, was a powerful force in the music business. He was characterized as “The Octopus” by Variety magazine for his far-reaching control and power in the record industry and his connections to organized crime. At one point, Levy owned more than 90 companies that employed 900 people.These included record pressing plants, tape-duplicating plants, a distribution company, a prominent New England chain of record stores, and numerous record labels.

Levy ruled his empire with an iron hand, using both fear and intimidation as part of his business model. In his book, Me, the Mob, and the Music, Tommy James characterized Levy as willing to strong-arm the artists signed to Roulette, and that the label was notorious for not paying its artists for their record sales.  Morris Levy - Roulette Records

Morris Levy - Roulette Records

In one disturbing incident, James wrote that Levy arranged a 1967 attack on former Roulette artist Jimmie Rodgers by an off-duty police officer in response to Rodgers’ repeated demands for unpaid royalties he was owed by the label. Rodgers, who had been Roulette’s top-selling artist in the 50s and early 60s with his #1 hit “Honeycomb” and 26 other charting singles, suffered traumatic head injuries from a blunt instrument in the beating.

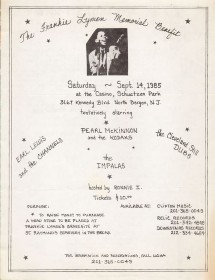

Back in New Jersey, Ronnie Italiano and the UGHA had adhered to Emira’s aforementioned wishes and held off on moving forward with their project to acquire and place a memorial tombstone on Frankie Lymon’s grave until her lawsuit was settled. With the trial about to begin and still believing that he had a firm agreement with Emira, Ronnie ran a second benefit concert in the fall of 1985 to raise additional funds for Frankie Lymon’s tombstone.

According to Bill Olb, the idea was suggested to Ronnie by Pearl McKinnon, who had recently left the reunited Teenagers. It was held on Saturday, September 14, at Schuetzen Park Casino in North Bergen, New Jersey. The flyer advertised performances by Pearl McKinnon and the Kodaks, Earl Lewis and the Channels, the Cleveland Still Dubs, and the Impalas. Watch a performance of "Little Boy And Girl" by Pearl McKinnon and the Kodaks.

Emira’s case was just beginning when Elizabeth Waters Lymon petitioned the Surrogate Court claiming that she was Frankie Lymon’s widow, and Zola Taylor also objected claiming that she was Lymon’s rightful widow. With the matter now in a confused state, the federal judge stayed Emira’s lawsuit. It was put on hold until the completion of a new trial to determine which of three women Frankie Lymon was said to have married, but none of whom he ever divorced, was his rightful widow and heir.

Morris Levy had not become a force in the music business through fear alone; he was also very clever. Frankie Lymon had been on his record label for most of his career, and Levy knew much more about the singer than Emira, who had only been with him for a year. Levy was aware of all the details of Frankie Lymon’s love life, and he used it to his advantage by bringing in Elizabeth Waters and Zola Taylor to challenge Emira’s claim to be Frankie’s widow and, by having the court determine her marraige to be invalid, derail her lawsuit.

Before the case came to court, Emira changed her mind about the tombstone, despite initially agreeing to have Ronnie Italiano and the UGHA to undertake the project. Her attorneys advised her that it might look bad for her in court if she allowed an outside organization to place a headstone on Frankie’s grave.

“Ronnie had raised a large amount of money from the benefit concerts and donations, but he had been in limbo because of the legal battle,” recalled Bill Olb. “He probably found out through her attorney, who Ronnie now had to deal with during the lawsuit.”

“His dealings with Emira had all been oral. There was nothing in writing in regards to the fundraisers or purchasing the headstone,” Olb said. “When you made a deal with Ronnie, it was usually oral, a real old-school type of business person. He was told, after he raised the money, that she didn’t want the headstone for the grave and that he wasn’t authorized to put it on there.”

Despite hearing that Emira had changed her mind, Ronnie maintained faith in their original agreement and ordered a headstone from a company in North Arlington, New Jersey. "Even though she had said no, she had said yes in the beginning; so Ronnie went ahead without going back and contacting Emira again. He figured that once the case was over there would be no problem," Olb recalled.

The beautiful granite tombstone that Ronnie ordered weighed over 1,000 pounds. It was engraved with the words, In Memory Of Frankie Lymon Sept. 30, 1942 - Feb. 27, 1968 "We Promise To Remember". The stone was dedicated by his fans and friends on February 27, 1988, the 20th anniversary of Frankie's death and one month before the opening arguments in the case that would determine his legal wife and rightful heir.

As soon as the hearing began, Emira’s attorney’s alleged that the other two widows “acted in concert” with Morris Levy. They pointed to the contracts that Elizabeth and Zola signed with Levy’s publishing business, Big Seven Music Corp. Each assigned the song’s copyright to Big Seven in exchange for an advance ($10,000 for Elizabeth and $7,500 for Zola) against her share of future royalties. Believing that she had the stronger case, Big Seven agreed to pay Elizabeth an additional $5,000 if the federal lawsuit was dismissed because the plaintiff (Emira) was determined to not be the legal widow.

Levy’s attorney responded that the agreements with Elizabeth and Zola amounted to standard industry contracts. He claimed that both women thought that their agreements with Levy were fair, and that neither planned to take legal action against him if she is found to be Frankie’s widow.

Levy declined direct comment of the Lymon matter. He was busy preparing for an April 11 trial for extortion and conspiracy in federal court in Camden, New Jersey, stemming from an F.B.I. investigation of the infiltration of organized crime in the recording industry. Levy had been arrested earlier in 1986 as part of the F.B.I. probe. His attorney called the charges complete speculation claimed and that there was absolutely no proof of Levy's guilt. When asked about his association with alleged mob figures, Levy, who was Jewish, responded: "I've been on Broadway 47 years. I know some of these characters, and some I like very much...I knew Cardinal Spellman, too. That don't make me a Catholic."

Meanwhile, Paula Span used both interviews and court testimony to profile each of the widows in her story. Elizabeth Waters was a struggling part-time bill collector from Philadelphia. She told the judge that Frankie Lymon was a charmer. “He had the type of personality that would draw people,” she said. She met Frankie when he was 20-years-old, backstage at the Audubon Ballroom in New York City. By 1962, Frankie’s career had been in decline for several years but she had nevertheless come with two girlfriends to meet her onetime idol.  Washington Post reporter Paula Span

Washington Post reporter Paula Span

Frankie was addicted to drugs and alcohol and Elizabeth, who was 19 at the time, was sympathetic. She told the court that she wanted to help him get back on his feet and regain all he had lost, but that trying to help him wasn’t easy. “Frankie was that kind of person, Your Honor,” Elizabeth said. “I can’t just sit here and tell the court anything different. Frankie could fool you, he could fool me; Frankie could fool God. That’s why we’re here today.”

She testified that she and Frankie had started living together shortly after they met. She had insisted that he check himself into a Manhattan hospital to cure his drug habit. He was clean for a time when she became pregnant in 1963, and he was deeply saddend by the death of their infant daughter.

Paula Span reported that Frankie and Elizabeth got married in Alexandria, Virginia, in early 1964. It didn’t last long, however. Frankie had started using heroin again, and she was forced to hide the money from his occasional gigs in a hole in the wall of their apartment to prevent him from using it to buy drugs. As a result, they fought and separated numerous times.  Elizabeth Waters Lymon

Elizabeth Waters Lymon

Elizabeth also acknowledged in court that she started using heroin and cocaine at this point. She also turned to prostitution to support her daughter from her first marriage, to one Charles Phillips, when she was just 16. Span wrote that Elizabeth called her work as a prostitute “moonlighting” in her testimony, and that Elizabeth said she had been arrested for it 15 or 20 times. “He (Frankie) sort of changed my life,” she told the judge. “A lot of people say I knew him so long I became like him.”

Elizabeth’s claim to be Frankie’s wife and heir was weakened by the fact that she was still legally married when she wed Frankie in 1964. Her divorce from Phillips was not finalized until 1965. Elizabeth’s attorneys argued in response that she and Frankie lived in Philadelphia and therefore established a common-law marriage under Pennsylvania law.

Frankie, by 1965, had pretty much been reduced to lip-synching at record hops on the East Coast. He decided to head to California in hopes that his old friend Zola Taylor could help him get some singing gigs in Los Angeles. Elizabeth testified that she did not object. “He had always regarded Zola as his stage mother,” she said.

Span wrote that Frankie’s relationship with Zola was not entirely maternal. Zola had also been a teenage star. Her singing group, the Platters, had been even more successful than the Teenagers, and the group was sometimes referred to as the Four Platters and a Dish. Zola, in her low-cut gowns, was the dish.  Zola Taylor with The Platters

Zola Taylor with The Platters

She and Frankie became teenaged lovers in 1956 while they were on an Alan Freed bus tour of 81 one-nighters, each performing with their group along with an all-star cast. Zola testified that their affair continued off and on for several more years.

According to Span’s story, Frankie moved into Zola’s home and her bedroom. He then called Elizabeth and urged her to join him. He told Zola that the new guest was “a friend from New York,” Zola recalled. Frankie told Elizabeth that “Zola and I aren’t doing anything; it’s just a motherly relationship,” Elizabeth testified in court.

Each woman suspected he was sleeping with the other, and both were apparently correct. When she and Frankie fought about it, Elizabeth told the court, he pulled a gun on her and fled. The following month, Zola testified that she and Frankie drove to Tijuana and got married in a tiny chapel. The small wedding party celebrated by getting very drunk, not an uncommon state for Frankie at the time. Span wrote that back in Los Angeles, the club where Zola was performing tossed a celebration with a cake and champagne.  Zola Taylor Lymon 1980s

Zola Taylor Lymon 1980s

Unfortunately for Zola, she was unable to locate records documenting her Mexican wedding to Frankie, or documentation of her Mexican divorce from her previous marriage (her second). Span reported that Zola’s secretary and her booking agent both testified that they were witnesses to the wedding, and that her attorneys argued that California law made her a putative (believed to be) spouse entitled to share in Frankie Lymon’s property.

Maybe it was the afterglow from her Tijuana marriage that induced Zola to trust a junkie like Frankie to take care of her financial affairs when she left to tour Japan with the Platters in December 1965. She let him live in her hillside house with instructions to pay bills out of an allowance forwarded to him by her attorney. When she returned in April, the house was in foreclosure and Frankie was gone with the money. Zola never saw him alive again.

“I’d have killed him, I was so angry,” Zola told Span. “But I couldn’t get my hands on him, couldn’t find him.” According to Elizabeth and several other witnesses, Frankie was back in New York telling them that his marriage to Zola had only been a publicity stunt.

Frankie had a very bad year in 1966. According to Paula Span’s story, he was arrested a least three times in New York for grand larceny or heroin possession, and the Selective Service, hungry for recruits as the war in Vietnam escalated, was after him. In lieu of sentencing, Frankie was allowed to undergo another rehab programAfter completing another rehab program and was inducted into the Army in December 1966.

Whie serving at Ft. Gordon in Georgia, Frankie married again. His bride was Emira Eagle, an elementary school teacher who lived with her family in nearby Augusta. According to Paula Span, her sister’s boyfriend introduced them, and soon after, Emira was cooking meals for Frankie and they were shopping for wedding rings. They were married in June 1967 at the Beulah Grove Baptist Church, with 50 members of Emira’s family in attendance and a reception afterward at the Capri Lounge.  Emira Eagle Lymon

Emira Eagle Lymon

Paula Span reported that neither Zola nor Elizabeth could quite figure Emira Eagle Lymon, the 48-year-old third wife from Augusta, Georgia. Frankie marrying a schoolteacher? "She's a square," Zola decided, noticing that Emira was coming to court in sneakers. Zola and Elizabeth didn't get close to Emira; and she didn't have anything much to say to them either during the 10 days they spent in court reliving the past.

Zola Taylor Lymon, who was 50, had flown in from Los Angeles. Span wrote that she was conscious of her stardom and arrived at court daily in a limousine. Zola got to be pretty friendly with the first wife. (All three women used the surname Lymon in court documents at least part of the time.) Elizabeth, now 46, said she had been born again, but she still strove for glamor, her skirt fashionably above the knee, her fingernails long and orange.

Although Emira’s attorneys advised her not to talk to Paula Span until the Surrogate Court reached a decision, Anne Pomeroy of the Artist Rights Enforcement Corporation, who was working with Emira’s lawyers, spoke with the reporter. “Emira’s Frankie Lymon is not this drunken bum,” Pomeroy said. “She did not know the druggie described in this trial. She knew a soldier.”

Frankie was interviewed by The Augusta Chronicle while he was stationed at Ft. Gordon. “While growing up in New York City, I never had much discipline,” Lymon said. “As a child star, however, I was subjected to discipline from agents, managers and lawyers, but it was a discipline that protected me from myself so to speak. Army discipline, I think, teaches a man how to protect himself. It teaches him responsibility and how to stand on his own two feet. It makes him not only a good soldier, but a better individual. I know it’s been good for me.”

Span wrote that Frankie was a soldier for most of his brief marriage to Emira. He took the bus to the post from her family’s home each day. He was a master manipulator, however, and it was just two months after his less than honorable discharge for repeatedly being AWOL that he went to New York, telling Emira that he wanted to see about reviving his career while also secretly planning to contact lady friends and drug pushers in the city.

At the trial, Elizabeth testified that she saw Frankie on that visit, as she had a number of times both before and after his wedding to Emira, which she said she knew nothing of. Elizabeth went on to testify that she also saw Frankie the day before he took his last, fatal dose of heroin.

Emira came to New York to arrange for Frankie’s funeral mass and burial. According to Span’s reporting, Emira paid the $2,000 bill. A headstone was not part of the package, however, and Frankie Lymon was buried in an unmarked grave at St. Raymond’s Cemetery.

According to Paula Span, people sometimes compared Frankie with the young Michael Jackson, who also knew how to combine innocence and knowingness. It was painfully revealed in court testimony, however, that Frankie Lymon, for all his talent, was a bigamist, hustler, liar, and thief. Consequently, he left behind a tangled and miserable legal and financial mess along with three wounded women.

None of the three women in court, all of whom he deceived and betrayed, seemed willing to condemn him. "He was honest, completely honest," Elizabeth insisted, "Up to a point." She said he didn't mean to hurt her, and blamed his behavior on his addictions. "Some drug users, they rob, they steal, and they do everything to sustain that habit." Frankie's particular scam, she believed, was getting married.

"I'm not a person to hold a grudge. I feel sorry for him, most of all," echoed Zola. She told Span that she never recovered financially from the loss of her home and still feels "cheated." Yet she also talked about Lymon's ruptured family, and, again, his drug dependency. "If you have any kind of heart at all," she said, "you know that he went through hell."

Parts of the above testimony and chronology of events were disputed in court. Emira’s attorneys argued that Elizabeth and Frankie separated in mid-1965 and never lived together as man and wife thereafter, invalidating her claim to a common-law marriage. They also pointed to the absence of documentation from Mexico as evidence that Zola and Frankie never married at all. Elizabeth’s lawyers, on the other hand, maintained her marriage was valid, which meant that neither Zola’s nor Emira’s could have been.

All these arguments were laid forth in voluminous briefs, memoranda, and affidavits filed in Surrogate Court. What seemed pretty clear from all the filings is the reason why, 20 years afterward, it had become so important to be Frankie Lymon's legal widow.

The elephant in the room was the large sum of money that would be awarded to whoever was determined to be the songwriters of "Why Do Fools Fall in Love.” It was copyrighted in the names of Frankie Lymon and Morris Levy. Leon Borstein, Levy's attorney, said that Levy "assisted in the writing of the song; you have to remember, if he added one word, that's sufficient" to justify co-authorship. Borstein also said that Lymon, who was always pestering Levy for money, sold Levy the copyright to all his songs and that Levy has a signed document to that effect. "Remember, Frankie needed the money badly," Borstein said. "He had been busted in California again for drugs. The sum,” he said, "might have been $1,500."

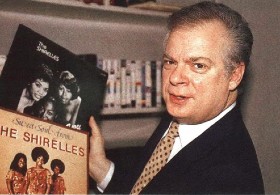

"Why Do Fools Fall in Love" was part of the American Graffiti film soundtrack and album, a big pop hit single and album for Diana Ross in 1981, and had been used in a greeting card commercial. By the time of the trial, publishing rights to the song might have been worth seven figures.  Chuck Rubin

Chuck Rubin

The monetary figure was estimated by Chuck Rubin, a former agent, who Paula Span described as “a kind of musical bounty hunter.” She also wrote that he established his Artists Rights Enforcement Corp. in 1981 to hound, bully, or sue record companies that he thought were depriving artists of their earnings, while taking a substantial cut for his efforts.

Artists Rights helped secure a financial settlement for Richard Berry, composer of "Louie, Louie" just before the song was used in a wine cooler ad. He also represented several of the artists featured on the "Dirty Dancing" album. Rubin's 200 or so clients constituted an honor roll of early rock and roll.

According to Span, Rubin was not opposed to generating new income from old music. "Sell, sell, sell," he advised. "Just make sure the artist or writer gets his share." Span wrote that Rubin gets his share too. Emira testified in Surrogate Court that her arrangement called for any money recovered through her suit to be shared 50-50 with Rubin, after expenses and legal fees, which had already reached a substantial subtotal.

The Surrogate Court judge hearing the widowhood case pushed for a settlement. Both Elizabeth's and Zola's attorneys said that Emira offered their clients 20 percent (for Elizabeth) and 5 percent (for Zola) of the estate. Zola and Elizabeth declined, but said they were willing to accept an equal, three-way split. Emira refused their counter offer. Paula Span reported that, during the trial, the judge even raised the disquieting possibility that none of his three supposed marriages was legally contracted, that Lymon had no widow.

Paula Span revealed that if Elizabeth or Zola was found to be his widow, they agreed to share the proceeds of his estate equally. If Emira won, she would share the proceeds with Chuck Rubin and go after Morris Levy. If none of the women was found to be Frankie's widow, the surviving members of his family stood to inherit.

In a matter that grew steadily more complex, Jimmy Merchant and Herman Santiago, the two surviving members of the original Teenagers, filed their own federal suit against Levy and his companies, with Emira also named as a defendant. The pair claimed they wrote "Why Do Fools Fall in Love" with Frankie Lymon and asked for a declaration of rights to the copyright of the hit song. "The only thing Morris Levy had to do with it was to collect the money," Santiago said.

The trial of the three wives went forward, and final briefs were due in early 1988. A decision was reached in November, but the case would not end there.