MRRL Hall of Fame

DENNIS COFFEY

- Details

- Category: Inductees

- Created: Friday, 01 June 2018 08:39

- Written by Gary Johnson

ertOne of the finest guitarists to emerge from the state of Michigan, Dennis Coffey made his first professional recording when he was just fifteen-years-old. He would go on to join the Royaltones, form a production company, and become an in-demand session guitarist. Coffey would also play an important role at Motown as a member of their famed studio band, the Funk Brothers, before launching a successful solo career in the 1970s.

Dennis Coffey was born in Detroit, Michigan, on November 11, 1940. His parents were not originally from Motor City, however. Coffey’s mother, Gertrude Schultz, was born in Copper City, located in the Keweenaw Peninsula at the northern tip of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Today, Copper City is a tiny town of under 200 people, but it was a profitable mining community in the late 1880s and early 1900s before the copper ran out. His father, James Coffey, was born and raised on a small farm in the hills of Kentucky and moved to Detroit when his father left his coal mining job for a higher paying job in the auto plants.

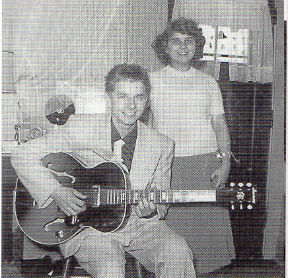

Gertrude and James met, married, and had two children in Detroit before Coffey’s father enlisted in the Navy during World War II. The couple divorced after he returned from the war, and Coffey and his sister, Pat, were raised in a single-parent home from that time onward.  Dennis Coffey with sister Pat and his first electric guitar

Dennis Coffey with sister Pat and his first electric guitar

Coffey wrote in his autobiography, Guitars, Bars, and Motown Superstars, that he came from a musical family on his mother’s side. His mother and his aunts all played the piano and sang. It was on a trip to visit his grandmother and the rest of his relatives in Copper City that he became enchanted with the guitar.

His cousins, Jim and Marilyn Thompson, were playing guitar and singing country music, and Coffey was totally fascinated. They showed him a few things on how to play guitar and that got him started. It helped that he had a guitar at home to practice on that had been given to him by his mother’s boyfriend. Coffey practiced relentlessly, playing and singing the songs of Hank Williams and learning anything he could about the instrument from other guitarists. By the age of thirteen, he had his first electric guitar.

By 1956, he had discovered rock and roll and was heavily influenced by Scotty Moore, Elvis Presley’s guitarist, and Chuck Berry. While in the tenth grade at Mackenzie High School in Detroit, Coffey felt confident enough to sing and play his guitar at a school assembly in the spring. After being introduced as “The Rock & Roll Kid”, he launched into Carl Perkins’ “Blue Suede Shoes” only to have the cord to his amplifier pulled mid-song by an older teacher who described the music and his performance as “obscene”.

Undeterred, Coffey started a rock and roll band at the age of fifteen. There were very few young rock and roll bands playing in Detroit in 1956, and Coffey’s band got a great response from their teen audiences. This led to a telephone call from a local singer named Vic Gallon, who was making a record and asked Coffey to put together a group to accompany him on two songs. Gallon promised to pay them $15 per song for a session lasting approximately two hours.  "I'm Gone" at 15

"I'm Gone" at 15

Recorded in a small basement studio on the northwest side of Detroit, the hands-down winner of the session was a cool little rockabilly number titled “I’m Gone”, containing an excellent Coffey guitar solo. Gallon pressed the record on his own Gondola label, and although it got airplay on Detroit’s WEXL-AM, it was not picked up by a bigger label for distribution. Listen to "I'm Gone" https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1OVlvDufWHQ

Coffey was knocked out hearing himself on a record for the first time but was disappointed that "I'm Gone" did not become a hit. Although this classic slice of early Motor City rockabilly failed to sell many copies at the time, the original 45s are now highly priced collector’s items.

By the following year, Coffey was performing as a duo with an Elvis look-alike named Durwood Hutto. The pair started writing songs together, and they decided to make a demo recording of the one they felt had the most hit potential, “Crazy Little Satellite”. The song was inspired by the Russian launching of Sputnik into orbit, and Coffey and Hutto recorded the demo at the Fortune Records Recording Studio in Detroit. After hearing their song, Fortune’s owner, Devora Brown, offered them a recording contract with her and Nat Tarnapol, Jackie Wilson’s manager and producer.

After co-signing a contract with their parents because they were underage, Tarnapol sent them to an apartment to rehearse their song with Berry Gordy and Billy Davis, who had just written Jackie Wilson’s first solo hit, “Reet Petite”. The following night, they recorded the single at the United Sound Studios on Second Avenue, across from Wayne State University. Berry Gordy produced the session, but “Crazy Little Satellite” was never released.  Coffey (left) with The Pyramids

Coffey (left) with The Pyramids

Coffey next step was to audition for a weekend band called the Rhythm Kings, that soon changed its name to the Pyramids. The Pyramids played weddings on Saturday nights and the circuit of teen clubs on Friday nights; and Coffey was paid $15 per night. The $30 he made each weekend was twice as much as he earned working afterschool all week as a cashier at a supermarket.

After graduating from high school, and unable to find a full-time job, Coffey volunteered for the draft and joined the Army. Stationed at Ft. Jackson in Columbia, South Carolina, he was able to play guitar in a band in a beer joint called the Sputnik Club when he was off-duty. It was also where he met his first wife, Joyce. After being promoted to corporal, Coffey got a regular gig with a band that played at the Noncommissioned Officer’s Service Club. The band’s piano player, John McCullough, had been involved in the production of the # 1 hit “Stay” by Maurice Williams & The Zodiacs.

Following his discharge and a brief and unsuccessful stint as a vocalist on May Records, Coffey moved back to Detroit with his new wife and seek his fortune in the music business. After a couple of years playing in the thriving bar band scene in Metropolitan Detroit, Coffey was asked to audition for the Royaltones, led by sax player George Katsakis. The Royaltones was an instrumental group from Dearborn that had a # 17 hit in 1958 with “Poor Boy” and reached the Hot 100 again in 1961 with “Flamingo Express”.

Shortly after joining the Royaltones, the group signed a recording contract with Harry Balk and Irv Micahnik, owners of Embee Productions and Twirl Records. At that time, the Royaltones line up consisted of Coffey on guitar, George Katsakis on sax, Bob Babbitt on bass, Marcus Terry on drums, and Dave Sandy on sax and lead vocals.

The company also hired the band to backup work in the recording studio for its artists, the most important being Del Shannon. Coffey and the Royaltones can be heard of several of Shannon’s hit singles including “Little Town Flirt”, “Handy Man”, “Do You Wanna Dance”, and “Keep Searchin’”. When the band recorded with Shannon, they would first rehearse the songs in Detroit and then record producer Harry Balk would fly them to New York, usually to do the sessions at Bell Sound in Midtown Manhattan.

Coffey wrote some songs that were recorded by the Royaltones during this time. The most successful of these was “Our Faded Love” on the Mala label in 1964. Co-written with George Katsakis, “Our Faded Love” was a big success in Detroit, reaching # 9 on power station CKLW; but it was only a minor hit nationally, peaking at # 103 on the Billboard chart. Listen to "Our Faded Love" https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S-K41jGnXcM

Coffey wrote some songs that were recorded by the Royaltones during this time. The most successful of these was “Our Faded Love” on the Mala label in 1964. Co-written with George Katsakis, “Our Faded Love” was a big success in Detroit, reaching # 9 on power station CKLW; but it was only a minor hit nationally, peaking at # 103 on the Billboard chart. Listen to "Our Faded Love" https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S-K41jGnXcM

Near the end of 1964, the Royaltones disbanded. George Katsakis went on to form a new band called the Court Jesters, which lasted until 1969; while Coffey joined a band that was backing singer Mickey Denton and Bob Babbitt began taking jobs as a studio musician.

By 1966, Coffey left Denton's band because he was getting so many calls to do session work for the many independent record labels that had sprung up in Detroit during the early 1960s. Bob Babbitt played bass with him on most of those sessions. Coffey got his first call to work at the Golden World Studios in 1965. Owned by Ed Wingate, Golden World and Ric Tic Records had emerged as a rival to Motown with national hits like “(Just Like) Romeo & Juliet” by The Reflections and “Agent Double-O-Soul” by Edwin Starr.

Golden World Studio was professionally designed and equipped with the latest in recording gear and audio technology. It had a high ceiling for string and horn overdubs along with a new recording console that was even more impressive than the one at Hitsville, Motown’s studio on West Grand Boulevard. Ed Wingate had a lot of money, and he wasn’t above secretly hiring Berry Gordy’s studio musicians to play on his sessions. Coffey saw Funk Brothers’ Benny Benjamin, James Jamerson, Mike Terry, Jack Ashford, and Eddie Willis moonlighting at Golden World.  (L to R) Don Davis, Bob Babbitt, and Coffey at a session in Detroit

(L to R) Don Davis, Bob Babbitt, and Coffey at a session in Detroit

Coffey met his future partner, Mike Theodore, at Golden World when they worked together on a project for Steve Mancha. They formed a production company called Theo-Coff Productions and made a deal with Tera Shirma Studios to go in at night, after the clubs had closed, and record local groups. Theodore did the engineering and Coffey arranged and conducted the bands. One of Theo-Coff’s important discoveries was a group called the Sunliners.

After sending out a demo of the band, the Sunliners were signed by Maverick Records of New York, which was distributed by MGM Records The group recorded an album, but when it didn’t sell, MGM pulled the plug on the Maverick label. The Sunliners changed their name to Rare Earth, got a new manager, signed with Motown, and had a big hit in 1969 with a live version of “Get Ready”, a song that Theodore and Coffey had first produced in the studio when they were still calling themselves the Sunliners.

During this time Coffey was playing guitar and/or producing, arranging, or writing a number of important releases on Detroit labels. These included “S.O.S. (Stop Her On Sight)” by Edwin Starr, “You’ve Got To Pay The Price” by Al Kent, “The Whole World Is A Stage” by the Fantastic Four, and “Real Humdinger” by J. J. Barnes on Ric Tic. Coffey was also involved with “(I Wanna) Testify” by The Parliaments and “Open The Door To Your Heart” by Darrel Banks on the Revilot label.

Coffey’s relationship with Golden World and Ric Tic ended when Ed Wingate decided to get out of the music business. Wingate sold his entire operation to Berry Gordy, and the Golden World Studio became Motown’s Studio B. In 1968, Coffey was offered a job paying him $138 a week to work from seven to nine each night, Monday through Thursday, with other musicians from Motown at what was called the Producer’s Workshop at Studio B. Motown’s idea was to use the workshop to help evaluate their in-house producers and to give them a chance to develop their ideas before going into the recording studio.

The hit song “Cloud Nine”, co-written by Norman Whitfield and Barrett Strong, came out of the Producer’s Workshop, and it became Coffey’s ticket into the Funk Brothers. The wah-wah pedal guitar effect that Coffey came up with in the introduction and throughout “Cloud Nine” was unique. The wah-wah pedal had been used in pop rock by guitarists such as Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton, but no one had used it or even heard of it in mainstream R&B. Listen to "Cloud Nine" https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2BdhhQayeWw "Cloud Nine" 45

"Cloud Nine" 45

The enormous success of “Cloud Nine” by the Temptations earned Coffey a regular slot in the Funk Brothers; and the song earned Motown its first Grammy Award in 1969. "Cloud Nine" was the first of Norman Whitfield’s psychedelic soul productions, and Coffey was now the guitarist and special effects specialist at Motown.

While the Producer’s Workshop was still happening, Coffey would often drive over to the Tower Studios on Grand River afterwards to do a session for Holland-Dozier-Holland. H-D-H had written and produced a great number of hit records at Motown for the Supremes, Four Tops, Martha & The Vandellas, and others, but they got into a dispute with Berry Gordy in 1967 over profit-sharing and royalties. They left Motown in 1968 and formed two record labels of their own, Hot Wax and Invictus.

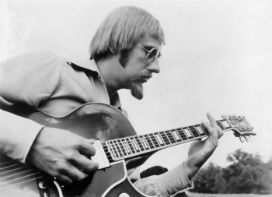

Coffey recorded several hits for the two H-D-H labels, including “Give Me Just A Little More Time” by the Chairmen of the Board, “Mind, Body and Soul” by the Flaming Embers, “Band Of Gold” by Freda Payne, and “Want Ads” by the Honey Comb before Hot Wax and Invictus closed amidst shrinking sales and lawsuits.  Dennis Coffey 1970's

Dennis Coffey 1970's

Now a hot commodity, Coffey received a phone call from Wilson Pickett’s record producers with an offer to pay him double scale and all expenses if he would fly down to Muscle Shoals, Alabama, and spend four days recording Pickett’s new album. “Don’t Knock My Love” was the first song they recorded. Coffey brought all his toys and doubled the bass line with a special guitar unit called the Condor. The Condor was built by the Hammond organ Company and consisted of a guitar and a keyboard device, which allowed him to push in stops and create sounds for the guitar such as an organ, harpsichord, bass, and bassoon.

“Don’t Knock My Love” was a big hit, reaching # 13 on the Hot 100 in 1971, and was also the title of what was to become Pickett’s last album for Atlantic Records. Two other songs from the album sessions featuring Coffey, “Fire and Water” and “Call My Name, I’ll Be There”, also charted when released as singles. Listen to "Don't Knock My Love" https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aZ0lwNceywE

Coffey worked on countless sessions with the Funk Brothers while Motown was still in Detroit. Some of the hits he played on included “War” by Edwin Starr, “I’m Livin’ In Shame” and “Someday We’ll Be Together” by Diana Ross & the Supremes, “It’s A Shame” by the Spinners, “Friendship Train”, “Nitty Gritty”, and “If I Was Your Woman” by Gladys Knight & the Pips, “That’s The Way Love Is” by Marvin Gaye, and “If I Were A Carpenter” and “Still Water (Love)” by the Four Tops.

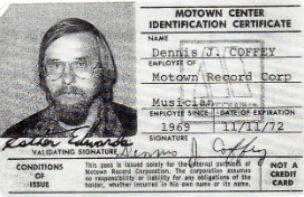

His most highly regarded work during this period was with producer Norman Whitfield and the Temptations. They followed up “Cloud Nine” with “Runaway Child, Running Wild” (# 6) in 1968, and “Don’t Let The Joneses Get You Down”(# 20) and “I Can’t Get Next To You” (# 1) in 1969. The following year saw “Psychedelic Shack” (# 7), “Ball Of Confusion"(# 3), and another # 1 hit with “Just My Imagination”.  Coffey's Motown I.D.

Coffey's Motown I.D.

Coffey wrote in Guitars, Bars and Motown Superstars that some people thought that Motown was like an assembly line, punching out records day after day with the same corporate sound. Since the company used the same musicians and equalization on each record and turned out so many releases, it may have seemed that way to outsiders.

He claimed that Motown was different. Coffey wrote that making records at Hitsville was a very creative process in which the whole was greater than the sum of the individual parts.

“The Motown Sound evolved the way it did because it was a regional sound that reflected the lives and experiences of the musicians who played it. The music had a funky feel, but because of the complex chord changes in the songs, the music went beyond being just another regional blues sound. Most of the vocalists at Motown had a slick, urban sound to their voices, which was different from the blues singers and southern funk singers who came out of Stax in Memphis and farther south. This vocal sound provided Motown with enormous pop crossover appeal, especially with groups like Diana Ross and the Supremes.”  Some Funk Brothers (L to R) Robert White, Danny Turner, Earl Van Dyke, Uriel Jones, James Jamerson

Some Funk Brothers (L to R) Robert White, Danny Turner, Earl Van Dyke, Uriel Jones, James Jamerson

The backing of the Funk Brothers was essential to the Motown sound. Being a later addition to the Funk Brothers, Coffey did not sign an exclusive agreement with Motown which forbade the musicians, under the threat of hefty fines, from doing sessions for other companies. He had already established himself as a valued studio guitarist with other labels, including Hot Wax and Invictus, and he was doing production work with his own company. When Harry Balk, then working for Motown, threatened to end his sessions with Motown if didn’t quit working with Holland-Dozier-Holland, Coffey told him, “As a free agent, I can work for anyone I want to, including H-D-H. If Motown doesn’t like it, don’t call me! No problem, case closed”

Coffey had called Motown’s bluff, and he was soon back in the studio. The situation was different for most of the other Funk Brothers. If you were a staff musician working every day for Motown, you signed exclusively with them and they paid you a weekly salary based on the number of sessions they expected you to do. The musicians had health insurance while they were working, but they had to relinquish the right to work for anyone else, which kept all the other major record labels from opening studios or offices in Detroit.

When Motown left Detroit in the early 70s, one of the music trade magazines listed the value of Motown Records at $70 million and the value of its Jobete publishing company at another $70 million. Coffey claims that If Motown hadn’t frozen out all the competition, musicians in Detroit could have made a very good living; but while Berry Gordy ended up with $140 million, the Funk Brothers got nothing, no recognition and not even a pension fund or medical benefits now that the company was gone.

Two years prior to Motown’s departure, Coffey signed a recording contract with Venture Records, a subsidiary label of MGM. He had been playing regularly with the Lyman Woodard Trio at Morey’s, a jazz club located in an upscale neighborhood in Detroit. When he got the go-ahead to record an album. He brought in Woodard on organ, Melvin Davis on drums, and Bob Babbitt on bass. “It’s Your Thing” was released as a single and reached # 1 in Detroit before the Venture label went out of business, killing any chance for the song to become a national hit.

He then signed with the Sussex label, which was distributed by Buddah Records. Coffey discovered Sixto Rodriguez in Detroit, and he and Mike Theodore produced his first album, “Cold Fact” in 1970. Although the album did not sell at the time, the lead track “Sugar Man” became an unlikely hit in South Africa year later. This eventually led to an Academy Award-winning documentary in 2012, Searching For Sugar Man, that brought Rodriguez belated international fame.

While working on his debut album for Sussex, Coffey created the sound of “Scorpio” by using a Sony Sound-on-Sound stereo tape recorder to record multiple guitar tracks in his basement. For the song's rhythm section, he secretly used several of the Funk Brothers. He then formed the Detroit Guitar Band featuring Bob Babbitt on bass, Eric Morgenson on keyboards, James Barnes on congas, Andrew Smith on drums, and Coffey on guitar to tour behind the resulting “Evolution” album.  Detroit Guitar Band (L to R) Bob Babbitt, Eric Morgenson, Andrew Smith, Dennis Coffey, James Barnes

Detroit Guitar Band (L to R) Bob Babbitt, Eric Morgenson, Andrew Smith, Dennis Coffey, James Barnes

Despite high expectations, the album failed to sell until some dance clubs in New York City began to play “Scorpio”, and Sussex decided to release the song as a single. “Scorpio” peaked at # 6 on Billboard’s Hot 100 and # 9 R&B. The hit single helped the “Evolution” album reach the Top 40 on both Billboard’s Pop and R&B album charts.

The success of “Scorpio” also enabled Coffey to become the first white artist to perform on Soul Train. He also made nationally televised appearances on American Bandstand and the Mike Douglas Show as a reult of the singles' popularity. Watch the kids on Soul Train dance to "Scorpio" https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CV3Al6CdmUQ

The following year Coffey and the Detroit Guitar Band released another successful album, “Goin’ For Myself”. “Taurus” was released as a single from the album, and it was another sizeable hit, peaking at# 18 on the Hot 100 and # 11 on the R&B chart.

In 1972, Coffey decided to get off the road and move his family to Los Angeles. He did sessions at Motown’s new MoWest Studio. It wasn’t the same, however, and Motown did not do as well in L.A. as it had in Detroit. It had lost most of the Funk Brothers in the move and, as a result, they lost the Motown Sound. Their records began to sound like all the other records made on the West Coast.  "Goin' For Myself" LP

"Goin' For Myself" LP

Coffey played on Ringo Starr’s “Goodnight Vienna” album, and Quincy Jones’ “Body Heat” LP while in California. He also got involved in television work, doing music for the S.W.A.T. television series and playing in the backing band for artists appearing on The Midnight Special and In Concert.

When the Sussex label went of business in 1976, Coffey moved back to Detroit. He and Mike Theodore signed to work with Westbound Records. Nothing much happened with Westbound, so Coffey pulled up stakes in 1979 and moved to New York City. Things weren’t any better in New York, however, as the music business was in a recession and no one was calling him for session or production work.

To support his family, Coffey took a sales job and returned to Detroit where he was hired on the assembly line at a GM plant. While working at the plant, Coffey recorded an album called “Motor City Magic” with the help of his old friend Georg Katsakis. He also hired former Funk Brothers Earl Van Dyke and Uriel Jones to play on the recording.

After a divorce, Coffey returned to college at Wayne State University and was eventually hired at a company called Detroit Art Services as a course developer and technical writer. This led to other jobs at ISI Robotics, and MXS International. In 1990, he found time to go into Studio A in Dearborn Heights and record his tenth studio album, “Under The Moonlight”. Since that time, he has also released “Flight Of The Phoenix” in 2006 and “Dennis Coffey” in 2011.

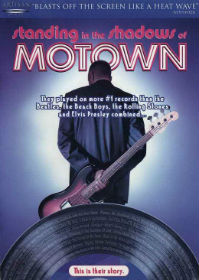

James Jamerson had been Coffey’s best friend at Motown and, in 1989, Coffey provided some stories about Jamerson to author Allen Slutsky for his book, Standing in the Shadows of Motown: The Life and Music of Legendary Bassist James Jamerson. Coffey also contributed to Paul Justman’s wonderful 2002 documentary on the Funk Brothers, Standing In The Shadows Of Motown. The film’s soundtrack won a Grammy Award in 2003 for Best Compilation Soundtrack Album for a Motion Picture, Television, or Other Media.

In 2017, Coffey released some vintage performances that he made as part of the Lyman Woodard Trio in the late 1960s at their weekly gig at Morey Baker’s club. The CD, released on Resonance Records, was titled “Hot Coffey in the D: Burnin’ at Morey Baker’s Showplace Lounge”. Later in the year, Coffey was inducted into the Rhythm & Blues Hall of Fame.  "One Night at Morey's: 1968 (Live)"

"One Night at Morey's: 1968 (Live)"

On June 1, 2018, Dennis Coffey was inducted into the Michigan Rock and Roll Legends Hall of Fame. That same month, another critically acclaimed CD from the 60s, “One Night at Morey’s: 1968 (Live)”, was released on Omnivore Records.

MRRL Hall of Fame: https://www.michiganrockandrolllegends.com/mrrl-hall-of-fame

Main Source: Guitars, Bars and Motown Stars by Dennis Coffey. 2004. University of Michigan Press.