Michigan Rock and Roll History

Ch. 10 - “The Birth of Motown”

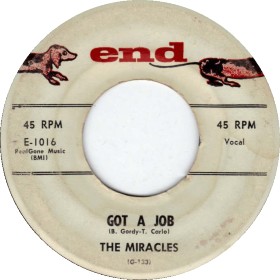

“Get A Job” by the Silhouettes had been a surprise # 1 hit on the Billboard Hot 100 in early 1958, and Berry Gordy Jr. helped Smokey Robinson write an answer song called “Got A Job”. Gordy had the group change its name from the Matadors to the Miracles before leasing the recording to End Records in New York. “Got A Job” was not a hit, but it was the first record Gordy produced and the start of a very important friendship and working relationship with Smokey Robinson.

Gordy had set up his own music publishing company as a result of his inability to collect his songwriting royalties from a New York publisher. He named it Jobete - a contraction using the first two letters of each of his children’s names; Joy, Berry, and Terry. An even more critical decision was made after Berry received a check for just $3.19 as his producer’s royalty for “Got A Job”. Smokey Robinson, who was with Gordy when he received the check, told him “You might as well start your own record label. I don’t think you could do any worse”. Listen to "Got A Job"

ln January of 1959, Berry borrowed $800 from the Gordy family savings fund to start Tamla Records. The fund had been started in 1957 by his parents, and each sibling had to contribute $10 a month. It worked something like a credit union, but to take any money out, it required a unanimous vote from the rest of the family.

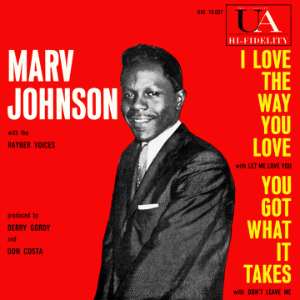

Berry already knew he wanted to record Marv Johnson as the first artist on his own label. He had first been impressed with Johnson when he heard his debut single on the tiny Kudo label in Detroit. He thought the young singer sounded like a cross between Jackie Wilson and Clyde McPhatter. Gordy helped fine-tune Johnson's original composition of “Come To Me”, and it would become the first Tamla single in 1959.

Featuring a flute solo by Beans Bowles, the recording was leased to the United Artists label for national distribution. The 45rpm of "Come To Me" was released on Tamla only in Michigan.

Gordy struck a deal with the American Record Pressing plant in Owosso, Michigan, to press the single; and he and Smokey Robinson drove to Owosso in a snowstorm in 1959 to pick up the boxes of those first Tamla 45s.

Marv Johnson’s “Come To Me” was a hit, peaking at # 6 on Billboard’s R&B chart and reaching # 30 on the Hot 100. Gordy served as Johnson’s manager, and he produced his records in Detroit at the United Sound Studios. The recordings were then released on the United Artists label for national distribution. Listen to "Come To Me"

Gordy started his Motown label in 1959, and its first release was the Miracles’ ballad “Bad Girl”. The song reached # 93 on the Hot 100 after it was leased by Chess Records for national distribution. Although it was only a minor hit, “Bad Girl” is now considered a classic doo wop single.

In the spring of 1960, Gordy merged the Tamla and Motown labels into a new company that he called the Motown Record Corporation. His new company lacked distribution, however, so his records were still being distributed nationally by larger record labels.

Even though his records were coming out on the United Artists label, Marv Johnson was Motown’s biggest star at this time. Johnson’s third single, “You Got What It Takes”, with Berry Gordy, Billy Davis, and Gwen Gordy listed as co-writers, became a # 2 R&B hit and also made it to # 10 on the Hot 100 in early 1960. As a result, Johnson began appearing on the big rock and roll package tours with other top artists of the day.

Controversy surrounded the hit, however, after it was discovered that Bobby Parker had written and recorded “You’ve Got What It Takes” in 1957 on Vee Jay Records. Parker claimed that Gordy stole the song from him but that Motown was too big to fight.

The songwriting credit became even more valuable years later when the Dave Clark Five covered “You Got What It Takes” in 1967 for a # 7 hit on the Hot 100.

Motown was not above a little thievery when it came to music during its early years. The Satintones, one of the early vocal groups signed to Motown, recorded six singles for the label between 1959 and 1961. The most notorious of these was a song called “Tomorrow & Always”. It had to be withdrawn for legal reasons, owing to a copyright infringement suit that alleged that the song was too similar to the # 1 hit, ”Will You Love Me Tomorrow”, by The Shirelles on Scepter Records in 1961.

Marv Johnson followed “You Got What It Takes” with “I Love The Way You Love”. It was also a # 2 R&B hit, but became his biggest pop success on the Hot 100 when it peaked at # 9. Even though he was signed to United Artists, he headlined Motown’s first package shows called Motortown Revues. Watch a performance of "I Love The Way You Love"

Johnson would chart three more singles in 1960 that Gordy either wrote or co-wrote, including his final Top 20 hit, “(You’ve Got To) Move Two Mountains”. Johnson had two more Gordy-produced R&B hits in 1961, and he appeared and sang two songs in the early rock and roll movie, Teenage Millionaire, starring Jimmy Clanton. When his United Artists contract was up, Gordy invited him to sign with Motown. In a fateful decision, Johnson decided to re-sign with the established major label rather than go with Gordy’s independent company.

As a result, Marv Johnson lost his manager, songwriter, and record producer. Gordy decided to put all his energy into Motown, and Johnson would have no further hits, even after he returned to Motown later in the decade. He would continue to record and perform until his death from a stroke in 1993 at the age of 54. Marv Johnson was inducted into the Michigan Rock and Roll Legends Hall of Fame in 2015, and “Come To Me”, the first Tamla single and his first hit, was voted a Legendary Michigan Song in 2017.

The most significant recording for Berry Gordy’s young company was “Money (That’s What I Want)” by Barrett Strong, one of Gordy’s early signings on Tamla Records. Written by Gordy and receptionist Janie Bradford, it was the first song recorded at Motown’s new home at 2648 West Grand Boulevard. Gordy married Raynoma Liles in 1960, and it was Liles who found the two-story house that would soon become famous as Hitsville U.S.A.  Barrett Strong

Barrett Strong

“Money” got a big boost when it was played by popular WXYZ radio DJ Chuck Daugherty who hosted a twice-weekly show sponsored by Coca-Cola called the Hi Fi Club, aimed primarily at a teenage audience. Radio DJs like Daugherty, broadcasting from AM stations all across the state, would play crucial roles in exposing the new artists and sounds of Michigan rock and roll, especially during its first two decades.

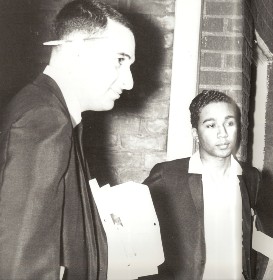

Al Abrams was Motown’s first employee. Born in 1941, Abrams was raised in a small Jewish community in Detroit and developed an early love of R&B music. After Gordy formed Tamla Records, Abrams was named National Promotion Director.

Over the years, Al Abrams became known for his innovative stunts to promote Motown releases, and he was Motown’s press officer during its rise to prominence in the 1960’s. It was Abrams who wrote Motown’s most famous catchphrase “The Sound Of Young America”.  Chuck Daugherty

Chuck Daugherty

It was Al Abram’s job to promote Barrett Strong’s recording of “Money”. He took a copy of Strong’s Tamla release and gave it to Chuck Daugherty who was doing a remote broadcast of his radio program. Daugherty liked the record, and he invited Abrams to bring Strong on the next show for an interview and to play “Money” in a phone-in segment called Make It Or Break It on which records were judged by listeners who phoned-in to the show.

The positive response from hundreds of callers led WXYZ to add “Money” to its playlist, causing a surge in record sales and other Detroit stations to start playing it as well. Gordy decided to distribute the record nationally on his sister’s Anna label that was connected to Chess Records.

"Money" quickly rose to # 2 on the R&B charts and hit # 23 on the Hot 100 in early 1960. Although it would be Barrett Strong’s only hit, it was the success of his record that made Berry Gordy decide to start distributing future releases on his own.Listen to "Money"  Al Abrams and Eddie Holland

Al Abrams and Eddie Holland

The Payola scandal over DJs being paid to play songs on the radio reached a new level of public prominence and legal gravity in February of 1960 when President Eisenhower called it an issue of public morality and congressional hearings were held over the practice.

The negative publicity had at least temporarily put an end to labels paying DJs to play their songs, but there were other ways of getting releases on the air. Having recording artists go to the radio studio to be interviewed on the air was a great way to get a record played. Others included having artists appear free of charge at dances hosted by popular radio DJs to lip-synch their songs, providing a legitimate opportunity for the DJ to earn extra money, or offering free services to them.

In the case of Chuck Daugherty, Motown hired him to shoot the label’s early publicity photos. When he rented a new apartment, Al Abrams brought young Motown employees, Lamont Dozier, along with brothers Eddie and Brian Holland, to help him move. Although they were unknown at the time, Holland-Dozier-Holland would go on to become Motown’s most important songwriting and production team of the 1960's.  L. Dozier, E. Holland, B. Holland

L. Dozier, E. Holland, B. Holland

Racial discrimination was not just practiced in the South. Blacks were restricted as to where they could live in Detroit through the use of racial covenants and various other racially-tinged agreements that resulted in segregated housing in the city.

Some restaurants openly refused to serve blacks in 1960, as Chuck Daugherty discovered when he attempted to buy lunch for Abrams and H-D-H after they helped him move. The five of them went to a nearby restaurant in Farmington, but the business refused to serve H-D-H and Daugherty ended up buying carry-out hamburgers for lunch.

Barrett Strong’s recording of "Money" was voted a Legendary Michigan Song in 2008. Strong would go on to great success as a songwriter at Motown while it was still based in Detroit. He teamed with Norman Whitfield to write some of the label’s biggest hits including “I Heard it Through The Grapevine”, “War”, “Cloud Nine”, “I Can’t Get Next To You”, “Just My Imagination (Running Away With Me)” and “Poppa Was A Rollin’ Stone”.

After Berry Gordy decided to distribute Motown’s records on its own, he made a crucial decision in hiring Detroit native Barney Ales, a charismatic and tough, street-smart music business veteran, who assembled a white sales team at Motown’s headquarters. They were the key to unlocking the doors to the record business establishment – a national network of distributors and promoters that could make or break a label’s product.

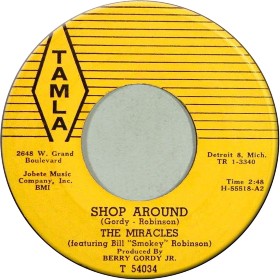

Ales and his team needed a big hit to work with, and Smokey Robinson came up with an idea for a song about following a mother’s advice called “Shop Around”. Robinson had Barrett Strong in mind when he and Gordy went into the studio to flesh out the chords. Forty minutes later, they had completed the song but Gordy convinced Robinson that the Miracles should record it instead of Strong.

Smokey Robinson produced the subsequent recording session. It was the first time that he had been in charge in the studio, and he recorded “Shop Around” with a slow, bluesy beat. The record was pressed and only released in Detroit, where it was given a test run.

Two weeks later, Smokey Robinson was awakened in the middle of the night by a phone call from Berry Gordy. He insisted that Smokey and the Miracles come to Hitsville immediately to re-record “Shop Around” with a different beat. Gordy told him that he was sure that this new version would be a # 1 hit.

It was still early morning when The Miracles assembled in the studio for the session. This time, Gordy took charge of the production and even played piano on the new version of “Shop Around” when Funk Brother Joe Hunter was unavailable.

Gordy’s premonition proved to be right on the money when the re-recorded version was released and distributed nationally at the end of 1960. "Shop Around" became Motown’s biggest hit yet in early 1961, peaking at # 2 on Billboard’s Hot 100 and spending 8 weeks at # 1 on the Billboard R&B chart. Motown was on its way. Listen to "Shop Around"